Centuries before the development of firearms, military thinkers considered ways to increase the “firepower” (to use an anachronistic term) of soldiers on the battlefield. One solution was to have archers shoot in a volley to maximize the impact of their arrows.

However, in the second century BCE in China, the “chu-ko-nu” was first developed – it was a repeating crossbow, and arguably the first “semi-automatic” weapon ever developed. Where even today crossbows can typically be slow to reload, the chu-ko-nu addressed the issue by employing a top-mounted magazine, in which multiple bolts were stacked.

It featured a large operating handle that when drawn to the rear would both cock the weapon and then release the bowstring, launching the bolt that had dropped into the flight groove. There was no trigger, and the ungainly weapon was difficult to aim and its range was just about 80 yards. But it did send a lot of bolts down range quicker than any archer could hope to shoot, and more importantly, it could be employed by largely untrained soldiers.

It was a true force multiplier on the battlefield, and not surprisingly, the chu-ko-nu remained in use through the 19th century when repeating firearms first entered the scene.

Roll Out the Barrels of Fun

Almost as soon as firearms were introduced in Europe, designers sought ways to increase the rate of fire, and they generally came to the same conclusion: add more barrels!

In the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance, the “ribauldequin” first appeared. Also known as a rabauld, ribault, or simply an organ gun, it was little more than multiple iron barrels lined up parallel on a platform. When fired the barrels would discharge their projectiles at once, yielding a little wave of fire at an enemy fire.

The Renaissance inventor/painter Leonardo da Vinci is credited for devising the concept in the late 15th century, but the first reported use of the ribauldequin in combat occurred in 1339 in France during the Hundred Years’ War, when King Edward III of England employed such a weapon with twelve barrels. Similar weapons were employed during the Wars of the Roses, while nine-barreled models were used by the various city-states during the Italian Wars of the 15th and 16th centuries. King Louis XII of France was noted to see the potential in the weapons and reportedly employed an organ gun outfitted with 50 barrels.

The weapons proved effective against massed forces, but the downside was that once fired it was all but impossible to reload for another volley.

Despite the limitations of volley guns, designers kept returning to the concept.

In addition to da Vinci, that included Josephus Requa, who like Richard Jordan Gatling – inventor of the Gatling Gun – had a medical background. However, where Gatling invented a gun that worked (one we’ll get to), Requa simply revisited a flawed idea.

Requa (a dentist by trade) had apprenticed with gun designer William Billinghurst and the two actively sought to create a rapid-fire weapon. The result was the Billinghurst Requa Battery Gun, which was little more than a line of twenty-five .58 caliber rifle barrels mounted together. Ammunition was loaded as a long magazine, and it was fired by a single percussion cap in a single volley.

The biggest advantage over the organ guns that preceded it was that a crew of three could reload and fire upwards of seven times a minute; resulting in a rate of fire of 175 rounds per minute. The U.S. military never actually adopted the Battery Gun but still purchased about 50 of the weapons, and during the Civil War, these weapons saw action in the sieges at Petersburg and Port Hudson and the Battle of Cold Harbor.

However, as military tactics evolved the practicality of the weapon became questionable. An organ gun was a reliable weapon when armies neatly lined up against one another, but the closeness of the barrels meant that two or three enemy soldiers would be hit by multiple rounds.

Wheel Lock and Load

It did become apparent to some early gun designers that a repeating firearm didn’t need more barrels, and instead, some of those inventors sought to address the rate of fire via the ammunition.

The first successful attempt to create a repeating “long gun” was the Kalthoff repeater, a firearm that appeared more than two centuries before the first lever action rifles were introduced. Developed by the prominent Danish-German family of gunsmiths, their firearm was a wheel lock ignited musket that could fire several stacked shots – similar to a Roman candle – while a matchlock at the breech served as a backup ignition system. It was later refined as a flintlock, which could fire between five and 30 rounds without reloading.

The Kalthoff repeaters saw use in the February 1659 Siege of Copenhagen against Sweden, and later in the Scanian War with Norway. Though an effective weapon for its day, its biggest drawbacks were its cost and that it had to be assembled with great care. Moreover, if a single part broke, the entire gun was unusable.

Crank It Up

A century and a half later, James Puckle, a British lawyer/writer turned inventor, developed his Puckle Gun – also known as the “Defence Gun” – a primitive crew-served, manually-operated flintlock revolver. Patented in 1718, it was notable for being even referred to as a “machine gun” in a 1722 shipping manifest. But it simply returned to the multiple-barrel concept.

It was also a complex weapon and expensive, and just two are known to have been produced.

Never used in combat, it is still notable for being among the earliest “revolvers” and for utilizing a crank handle to rotate and fire its nine square bullets. Because it still relied on flintlocks, it was slow to reload and once fired would serve little purpose. However, at the time a trained soldier would have to work very hard to fire three shots a minute, whereas the Puckle Gun could fire nine bullets in a few seconds. Puckle offered his design to the Royal Navy, which passed on it, but he did manage to find a buyer in John Montagu, the 2nd Duke of Montagu, the son-in-law of John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough. Montagu was a collector of oddities, and the two Puckle Guns remain in the collection of his former estate.

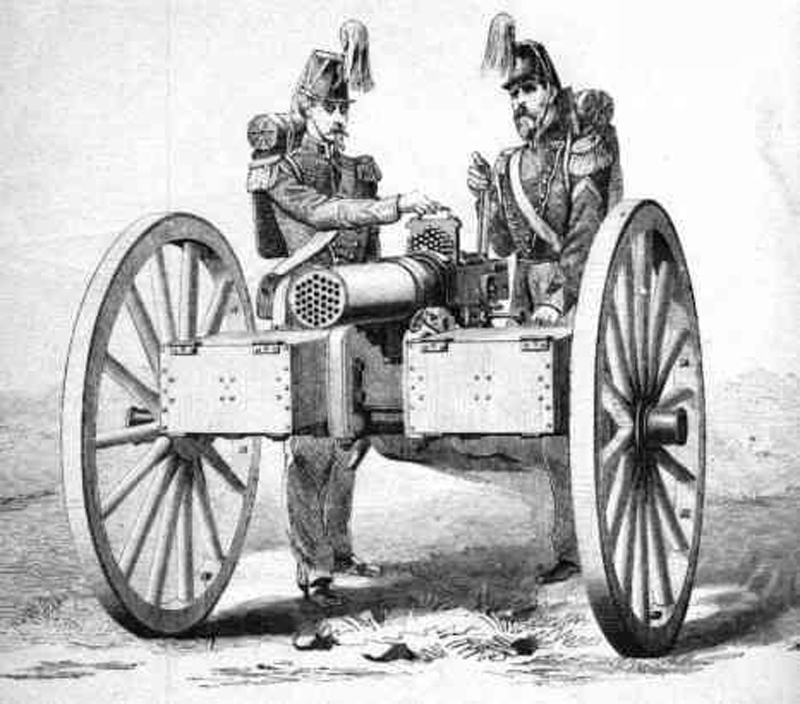

The Puckle Gun may have been ahead of its time, but the concept of a crank-operated firearm was further improved by Belgian Army Captain Toussaint-Henry-Joseph Fafshamps and manufactured by Joseph Montigny of Fontaine-l’Everque. The Montigny Mitrailleuse featured 37 barrels and was capable of firing nearly 300 rounds per minute, however, instead of independent fire from those barrels, it fired volleys of ammunition. Loading/reloading was accomplished by way of a pre-loaded ammunition plate that was inserted at the breech.

The Montigny Mitrailleuse saw limited use with the French Army in the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71), where it was employed at the Battle of Gravelotte to devastating effect.

About the Founding Fathers and Automatic Weapons…

One firearm that certainly deserves to be mentioned is the Belton flintlock, among the earliest true repeating muskets. It could fire up to sixteen consecutive shots in as little as 20 seconds. What is especially noteworthy about Joseph Belton’s design is that he had offered it to the Continental Congress, which does counter the argument that the Founding Fathers drafted the United States Constitution when single-shot flintlocks were the most advanced firearms of the day.

This should serve as proof that those Founding Fathers had some understanding of the concept of rapid-fire weapons!

Just as noteworthy is that neither the Continental Army nor the British Army showed any interest in Joseph Belton’s design – largely due to its high cost – and it would be nearly another century before the armies of the world began to adopt repeating firearms. However, there is no denying that multi-shot weapons were available when the Second Amendment was drafted while no effort to preclude such weapons from civilian ownership was even considered.

Still More Barrels and Yet More Cranking

Throughout the early industrial revolution firearms technology saw considerable innovations. Cartridges were introduced, while repeating rifles were developed. Yet, most efforts to produce a high rate of fire fell back on the old concept of adding barrels.

It fell to the aforementioned Dr. Richard Jordan Gatling to do more than just make an oversized organ gun or large revolver. Gatling had already been a prolific inventor who developed the screw propeller, a wheat drill for planting, a steam tractor, and even a motor-driven plow. Yet, it was his Gatling Gun that he is most certainly remembered for today.

An irony is that the first successful rapid-fire gun was developed not to kill more soldiers, but rather to reduce the need for so many soldiers on the battlefield!

During the American Civil War, Gatling saw how more soldiers died of disease than from gunshots. He sought to develop a weapon that could supersede the need for large armies, in the hope that deaths from disease would be diminished.

His mechanical machine gun was a forerunner to the weapons that were to come. The Gatling Gun’s operation centered on a cyclic multi-barrel design that allowed for its rapid fire, but also facilitated cooling of the barrels. Although the Gatling gun did see some limited use in the Civil War it wasn’t officially adopted by the U.S. Government until 1866, when it was employed by the U.S. Cavalry on the frontier. In one famous story, Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer chose not to bring his Gatling Guns with his forces at the time of the Battle of Little Bighorn – and one can only speculate if the battle may have turned out differently had he utilized the weapons to their full effect.

Maxim(um) Effort

It was finally another American, Hiram Stevens Maxim, who succeeded where the others failed. Maxim was a tinkerer who had a slew of inventions to his name. During a trip to Europe, he met with a fellow American who reportedly told Maxim, “Hang up your chemistry and electricity! If you want to make a pile of money, invent something that will enable these Europeans to cut each other’s throats with greater facility.”

The concept of a machine gun came to Maxim when he was knocked over by the recoil from a rifle, and his design employed one of the earliest recoil-operating firing systems. The concept remains in use today, where the energy from the recoil on the breech block is used to eject a spent cartridge and insert the next one. The Maxim design could fire 600 rounds, allowing a lone soldier to have the firepower of an entire line of troops. And it only required a single barrel!