Historic “firsts” are often heralded as those critical moments that changed the world forever. In the case of military hardware, this fact cannot be understated. That would certainly be the case with the clash of the ironclad warships USS Monitor and CSS Virginia at Hampton Roads in March 1862. Likewise, it was during the Battle of the Somme on September 15, 1916, that the British Army first deployed tanks into battle.

Less remembered, but no less significant was the first use of the airplane in war (October 23, 1911) during the Italo-Turkish War, when an Italian pilot made a one-hour reconnaissance flight over enemy positions near Tripoli, Libya. It was a rather uneventful moment, which is likely why it has been largely forgotten.

Moreover, the history of firearms in war is less clear, in part because of a lack of record keeping, while the significance wasn’t fully understood at the time. What we do know is that Chinese monks discovered the technology to make gunpowder in the 9th century, but it has been lost to time when it was first employed in a conflict. We also know that the Arabs gained the knowledge of gunpowder in the early 13th century and it was employed by the Mamluks against the Mongols at the Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260.

The earliest mention of gunpowder in Europe appeared in Roger Bacon’s Opus Majus seven years later, but within a few decades, it was noted for its use in ship-to-ship combat. Within a few centuries, firearms changed military tactics, and arguably continue to do so.

Enter the Machine Gun

It is certainly known that there were attempts to develop a firearm capable of repeating discharging rounds, and the Gatling gun became one of the earliest rapid-fire weapons to see success when it was used in a limited capacity during the American Civil War.

However, the first true machine gun wouldn’t have its baptism of fire until three decades later.

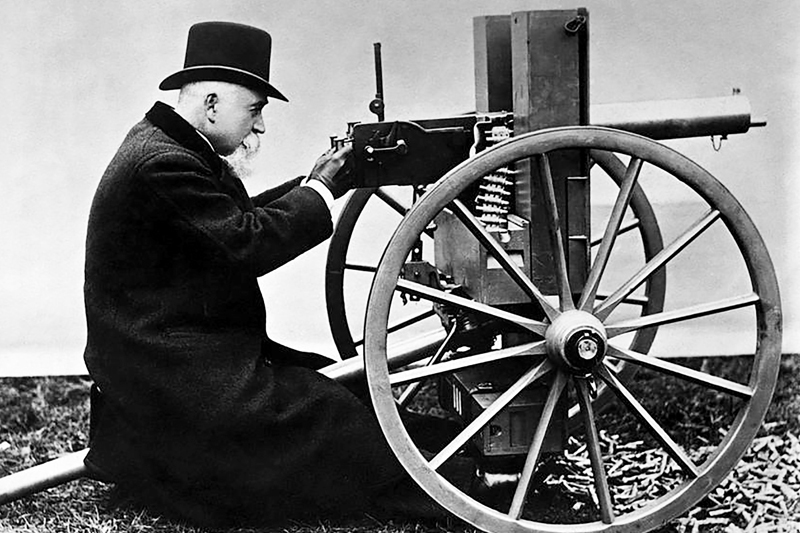

American-born inventor Hiram Stevens Maxim has been noted for developing the first successful fully automatic machine gun. His design would greatly influence future machine guns, while it certainly played a significant role in the carnage of the First World War – as many of the great powers employed derivatives of the Maxim or firearms meant to compete with it.

There is also a common misconception that generals of the First World War had no idea of the machine gun’s capabilities, but by that point, the Maxim gun had already been battle-tested for more than two decades. It would be wrong too to suggest that most military thinkers thought the machine gun was merely a novelty or a fad. This completely ignores the fact that efforts had been made to improve the weapons – just as all firearms technology had made steady improvements at the end of the 19th century.

Before the First World War, there was simply a belief by the various leaders that their tactics were superior to the enemy’s and they expected a short war. They certainly knew the machine gun was deadly – that fact was made clear in the colonial wars in Africa and Asia, in the Spanish-American War, and notably the Russo-Japanese War.

The very lesson of how devastating the machine gun could be was first noted 130 years ago on October 25, 1893, in what is modern-day Zimbabwe.

The Battle of the Shangani

In what might be one of the most lopsided engagements in history, the Battle of Shangani was fought during the equally lopsided First Matabele War, which took place from October 1893 to January 1894. It saw 750 troops of the British South Africa Company (BSAC) – essentially the private military force of Cecil Rhodes – along with 1,000 native volunteers take on a force of more than 80,000 Ndebele (Matabele) Kingdom spearmen and 20,000 riflemen.

Anyone who has seen the movie “Zulu Dawn” may recall the British Army’s cockiness, and how the British suffered the worst defeat of a modern army in history. This wasn’t the case at Shangani.

The BSCA didn’t underestimate its foe and went in ready for a serious fight when it responded to a raid conducted by warriors from the Ndebele Kingdom. The force of paramilitary troops were well-trained but more importantly armed with modern rifles, two cannons, and notably five Maxim guns as well as three other rapid-fire guns – reported to be Gatling guns.

The Ndebele may have had the numbers, but the BSCA had Maxims!

A Prepared Defender

Perhaps hoping to secure a victory like the Zulu had at Isandlwana in January 1879, Ndebele King Lobengula planned a surprise attack at night led by his generals Manonda and Mjaan with around 5,000 warriors – but the BSAC took precautions and set up camp at the Shangani River, forming into a circular defensive “laager” technique that was pioneered by the Boers, the descendants of the original Dutch colonists. With this corral or wagon fort, the BSAC forces were already in a well-fortified position.

BSAC sentries were also on high alert when the Ndebele launched their attack in the early pre-dawn hours. The South African forces sprung to action and opened fire on the charging enemy with the Maxim guns. An eyewitness described how the warriors were mowed down “literally like grass.” Wave after wave of Ndebele warriors were slaughtered. By the time the attackers withdrew, they had suffered around 1,500 fatalities. The BSAP lost four men, reported to be scouts who had failed to make it back to the laager.

For the British military, that brief engagement proved the effectiveness of the Maxim and it became central to battles in Africa through the latter colonial era. Just a week later, another force of Ndebele attacked a unit of the BSAC, but again the machine guns simply added to the butcher’s bill killing an additional 2,500 warriors. It has been suggested the numbers might have been higher had the BSAC not run low on ammunition.

Other Lessons From History

The Battle of Shangani may have been the first time the machine gun was employed in a battle, yet, the British Army had already seen firsthand the devastating effect rapid firepower could have in a battle.

Though a movie was made about the British Army’s defeat at Isandlwana and the film “Zulu” also depicted the heroic stand at Rorke’s Drift the next day, there has not been a film about the Battle of Ulundi – where 4,200 British and 1,000 African volunteers defeated 15,000 Zulu warriors in their capital. The British employed Gatling Guns and fought in a well-defended “square.” The British saw fewer than 20 killed, while the Zulu lost nearly 500.

Five years after Shangani, an Anglo-Egyptian force attacked the Sudanese army of the Mahdist State on September 2, 1898, at the Battle of Omdurman. Maxim guns, along with artillery from gunboats on the Nile tipped the scales in the favor of the British-led forces.

Fewer than 30,000 Anglo-Egyptian troops successfully defeated more than 52,000 Sudanese. When the battle ended, the Anglo-Egyptian troops had lost 48 killed, with another 382 wounded. The Sudanese saw 12,000 killed and another 13,000 wounded.

The British military clearly saw the potential of the machine gun.

That same year, Franco-English writer and historian Hilaire Belloc wrote in his book of poems, titled “The Modern Traveler,” “Whatever happens, we have got, the Maxim gun, and they have not.”

The Machine Gun Lives On in Infamy

Today, firearms historians will still debate whether or not the Maxim was among the most effective machine guns in history. It certainly left its mark in multiple engagements in Africa and then on the battlefields of the First World War. And in the latter case, the military leaders simply failed to realize that Belloc’s take on the Maxim no longer applied.

However, “Whatever happens, we have got, the Maxim gun, and so too does the enemy” just doesn’t ring the same!