For those with a Model 1911 in their holster, gun cabinet, or display case, today might be a good day to head to the range with it or just take a moment to appreciate this particular firearm. While the 1911 can be admired and celebrated year-round, March 29 is a special day for the 1911, marking the anniversary of its adoption by the United States military. The gun may no longer be the primary sidearm of soldiers, sailors, marines, and airmen, but it is still revered by special operators worldwide as a reliable, rugged firearm that can get the job done.

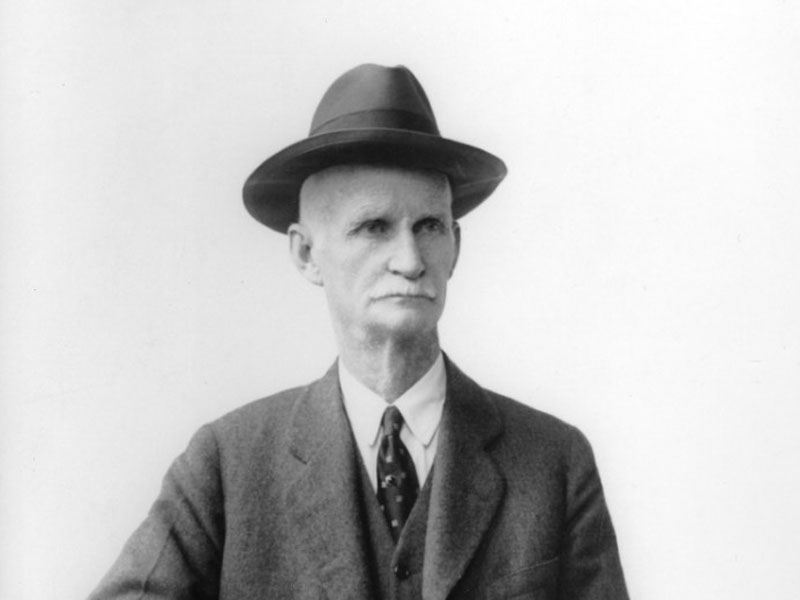

The 1911 pistol has been around so long and has become so prolific that some might even be forgiven for not knowing its full story or even who designed it. Of course, any shooter worth his weight will tell you it was one of John Moses Browning’s designs – and arguably one of, if not his very best.

A Firearm Ahead of Its Time

While Browning wasn’t exactly born with a gun in his hands, he certainly grew up around firearms. His father wasn’t a lawman, outlaw, or gunslinger, but rather Jonathan Browning was an inventor who trained as a blacksmith before becoming a gunsmith after an apprenticeship with Samuel Porter in Nashville, Tennessee. The elder Browning even began producing his firearms in 1831 and invented a “sliding breech” repeating rifle at his shop in Quincy, Illinois a few years later.

From a young age, John Browning was exposed to firearms so much that he may have had gun oil in his veins, so it isn’t surprising that with his brother he founded a company bearing the family name to make sporting rifles and handguns. Yet, Browning’s designs also caught the eye of the U.S. military, and throughout his career, his designs included the Model 1895 “Potato Digger” machine gun, the M1917 water-cooled machine gun, the M1919 air-cooled machine gun and the Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR).

Yet, among the most famous of Browning’s designs was the Colt M1911 .45 pistol, used by the U.S. military from 1911 until 1986 when the 9mm Beretta M9 pistol finally replaced it. Even today modernized variants of the M1911 are still used by the U.S. Army Special Forces and U.S. Navy.

The Sidearm The U.S. Military Needed Like No Other

A case could be made that many firearms were invented or developed for which some military planners didn’t see a need. That could be true of repeating rifles and, notably, the machine gun. However, such was not the case with the M1911.

The United States Army knew the sidearms it had in service at the dawn of the 20th century were certainly not getting the job done, and something “new and improved” was needed. Interestingly, it was due to a distant conflict that is now largely forgotten – one that wasn’t all that different from the recent Global War on Terror (GWoT).

To understand this, we must remember that when the United States went to war with the Empire of Spain in April 1898, there were roughly 2,100 officers and 26,000 enlisted men in the U.S. Army. The U.S. was far from the superpower it would become less than half a century later.

Yet, that number would swell to nearly 80,000, and even if it was hardly a sizeable force compared to the other world powers of the day, the U.S. arsenals didn’t have modern weapons available to all of its soldiers. As a result, many of the U.S. soldiers were issued weapons that could be described as antiquated – including the Springfield Model 1873 rifle. The only bright side was that the Army’s standard sidearm, the Colt M1892 .38 Long Colt Revolver, was among the better firearms of the day – at least compared to the other military revolvers in service at the time.

The Colt M1892 .38 Long Colt Revolver

The revolver featured a counter-clockwise rotating cylinder, and it could be opened for loading and ejection by simply pulling back on a catch mounted on the left side of the frame. Empty cases could be easily removed by simply pushing back on an ejector rod to activate a star extractor. The six-shooter revolver could be quickly reloaded and the cylinder clicked back into place.

United States Marine Corps officers also employed the M1892 revolver during the Boxer Rebellion in China (1901), while some British officers preferred it as their sidearm of choice during the Boer War in South Africa (1899-1901). It performed reasonably enough in those conflicts, as well as the aforementioned Spanish-American War.

However, the Colt M1892 .38 Long Colt Revolver was found not to be up to the rigors of jungle warfare during the Philippine-American War and Moro Rebellion. One problem was that the weapon performed poorly in humid conditions, but the bigger issue was that the .38 caliber didn’t have the necessary stopping power in the latter conflict.

The Philippine-American War

The largely forgotten Philippine-American War – also known as the Philippine Insurrection – wasn’t all that different from the war the United States fought against Spain, and despite the issues with the climate, the M1892 was acceptable enough. The performance of the sidearm in the Moro Rebellion that coincided with the Philippine Insurrection was another story entirely.

The indigenous people, known as the Moro, were known as extremely tough warriors and despite Spanish rule for centuries, the Moro had never been completely subjugated. They wore armor with plates made of either black water buffalo horn or brass plates connected with butted brass mail, and donned Spanish-style helmets that seemed out of the “conquistador era.” By that description, it would seem the U.S. had a huge advantage, and many soldiers underestimated the Moros.

The Moro warriors often took strong narcotics to inhibit the feeling of pain in battle, while the hallucinatory effects would allow the warriors to feel almost invincible. Between the armor and the drugs, the .38 round lacked the stopping power the U.S. Army required.

Stories were told of U.S. junior officers and NCOs found lying dead with their throats cut next to a dead Moro warrior who had taken six shots to the chest.

The situation was so desperate that soldiers reverted to the M1873 single-action revolver in the .45 Colt caliber as the heavier bullet proved to be more effective against the charging tribesman. The message was clear. The U.S. Army needed a better sidearm, and the U.S. Army’s Chief of Ordnance, General William Crozier, authorized testing for a new service pistol and cartridge to go with it.

A New Cartridge

The .38 cartridge was seen as the problem – but as it happened, Browning was already tinkering with a self-loading or semi-automatic pistol and a new cartridge. In 1904, he developed the .45 Automatic Colt Pistol (ACP), also known as the .45 Auto, a rimless straight-walled handgun cartridge. The round was selected during the Thompson-LaGarde Tests conducted by the U.S. Army to replace the .38 Long Colt cartridge.

Colonel John T. Thompson, who would later develop the Thompson submachine gun chambered in the .45 ACP after the First World War, and Major Louis Anatole LaGarde of the U.S. Army Medical Corps oversaw the tests at the Nelson Morris Company Union Stock Yards in Chicago, Illinois. It involved using both live cattle outside the slaughterhouse as well as some human cadavers. When employed against the donated corpses, the distance the body swung when hit by the round was measured, and that was used to determine the bullet-stopping power.

The .45 ACP was tested against other cartridges of the day, including the 7.65×21mm Parabellum (.30 Luger), 9×19mm Parabellum (Germany), .38 Long Colt, .38 ACP, blunt and hollow-point .45 Colt (U.S.), .476 Eley (UK), and the “cupped” .455 Webley (UK). Following the tests, Col. Thompson recommended that the new pistol should not be less than .45 caliber and that it would be semi-automatic in operation.

The 1906 Pistol Trials

The U.S. Army was certainly determined to select the best pistol, and seven firearms manufacturing companies, including Colt, Bergman, Deutsche Waffen and Munitionsfabriken (DWM), Savage Arms Company, Knoble, Webley and White-Merriell, took part in the 1906 trials.

While it may now be impossible to consider that the Army could have adopted anything other than the Colt M1911 .45 pistol – which became just one of many of the weapons Browning designed for the U.S. military – another firearm seemed to be even more well-liked: the P08 Luger.

Developed by Georg Luger, who worked closely with arms designers Ferdinand von Mannlicher and Hugo Borchardt, the P08 was the first semi-automatic service pistol to be adopted by any military. Luger continued to seek buyers for his new pistol, and when Germany did initially adopt a weapon, it was in the newly designed 9x19mm Parabellum round also designed by Luger.

In the 1906 pistol trials, the Luger was considered alongside designs by Browning, who was then working for Colt and Savage. The U.S. military required that each designer supply 200 examples in .45 ACP. The Army had already purchased some 1,000 7.65 Lugers and a few in the 9mm, but it required the pistols be in .45 ACP.

As the 1906 trials progressed, there were three finalists: Colt, Luger, and Savage.

Colt versus Savage

Both Savage and Colt manufactured their respective quota of 200 weapons, but Luger only made two. Georg Luger had felt that it was doubtful that his foreign design would be successful over two American contenders and essentially withdrew from the competition.

The 1906 .45 Savage Auto seemed to be the frontrunner at the time. The delayed blowback pistol had nine fewer parts than the Colt design, held more rounds than the Colt, and notably required fewer tools to be completely disassembled. It was more accurate than the Colt and even passed the sand test in half the time the Colt took.

Yet, unfortunately for Savage, it also had 40% more jams and misfires than the Colt. The board further found the Savage to be quite violent in discharge and heavy – even as the board’s own report lists the Savage as weighing only 1/2 ounce more than the Colt. In addition, the board found the Savage Auto to have the same deficiencies as the Colt, including no loaded chamber indicator and no automatic safety.

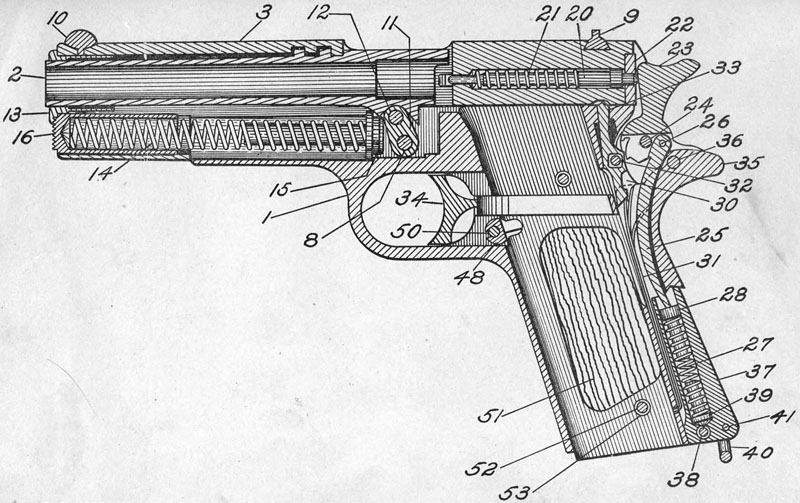

Field tests of the Colt and Savage pistols continued for several years, during which John Browning worked with Colt to address any issues, while Savage also carefully refined its pistol. At one point, Savage reportedly even put political pressure on the military, but in the end, the final showdown occurred on March 15, 1911.

The Final Showdown

The Colt-improved Model 1911 went up against the Savage Model 1910. More than 6,000 rounds were fired from each of the two pistols. The Savage had 37 misfires, while the Colt had none. In addition, the Colt consistently grouped better in the accuracy tests and was much quicker and easier to disassemble than the Savage. The four years of refinement under John Browning’s watchful eye resulted in what was seen as a firearms masterpiece.

The Colt M1911 was unanimously approved by the U.S. Army Testing Board and adopted on March 28, 1911. By late April of that same year, contracts totaling more than 30,000 pistols began a relationship between the Army and Colt that would last 75 years and produce a total of more than 6 million pistols.