The M-16 is America’s longest-serving military rifle, dating to the US Air Force’s initial 1962 adoption. The M-16’s various incarnations, including the M-4 carbine, have proven among the world’s most effective combat rifles, despite some early rough patches caused by US Army bureaucracy. As the M-16 nears the end of its American service life, let’s look back at this remarkable weapon, its creator, and how it succeeded.

Fair warning: this is a general article dealing with the M-16’s basic history. Not all models and variations are mentioned. Books are written about that stuff. Nor is this an M-14 hit piece. I love the M-14. I think it’s an awesome rifle. But it’s ill-suited to modern close combat operations, just as it was in Vietnam.

Battlefield Realities

World War II revealed that mobile infantry armies needed lighter, faster-firing weapons that could be effectively mass-produced. Most nations addressed that need with simple, pistol-caliber submachine guns like the American M3 “Grease Gun,” the British STEN, the Soviet PPsh, and the German MP-38 and MP-40. The United States also had the M1 Carbine, which was originally intended for support troops. But the compact, lightweight Carbine soon saw front-line service and was the war’s most-produced American small arm. The Army introduced the 30-round select-fire M2 Carbine late in the war, but it wasn’t widely issued until five years later in Korea.

The Germans and Soviets took it a step further. The Americans and British used lighter weapons but still saw their .30 caliber battle rifles as the standard infantry weapon. Germany recognized the need for a smaller, lighter infantry rifle chambered for an intermediate cartridge, resulting in the StG-44 Sturmgewehr, which initially sparked the “assault rifle” label. The Soviets reached similar conclusions, developing the SKS and then the AK-47 around their new 7.62×39 cartridge. The new rifles were easier to carry, and soldiers could pack more firepower thanks to the shorter, lighter cartridges.

But the US lagged behind, clinging to the “full power” .30 caliber cartridge, despite evidence showing that most infantry combat occurred within 300 yards and that most infantrymen rarely fired at anything past 100 yards. The ingrained American idea of accurate, deliberate, aimed fire was mostly a myth dating back to the American Revolution.

The Korean War

Korea amplified America’s small arms shortcomings. US soldiers and Marines faced waves of North Korean and Chinese soldiers in numbers that American arms had never seen. The 8-round, semi-automatic M-1 Garand was suddenly insufficient, and the select-fire M-2 Carbines couldn’t pick up the slack. It didn’t help that those weapons fired different cartridges, requiring independent production and supply chains. The US military needed a single select-fire infantry rifle, and it needed that rifle yesterday.

Even so, the United States didn’t adopt a new rifle until four years after the Korean War ended. Worse still, despite the evidence, the Army bureaucracy insisted on a .30 caliber battle rifle, albeit with the new, shorter 7.62×51 cartridge, which was based on the .308 Winchester. The result was the Springfield Armory M-14, a cool rifle that was nonetheless obsolete when it was adopted. But a previously unknown engineer had quietly developed a radical new design. His name was Eugene Stoner.

The Armalite Rifle

Eugene Stoner was a Marine in World War II, where he worked as an aviation ordnance technician in the Pacific. That made sense because his first job after graduating high school in 1940 had been installing things that go bang for Vega Aircraft Company.

Stoner worked in aircraft engineering after the war before landing at Armalite, the small arms division of the Fairchild Engine and Airplane Corporation. Stoner used his experience with lighter aluminum alloys and fiberglass to create the AR-5, a lightweight survival rifle for the US Air Force. “AR,” by the way, stands for “Armalite Rifle,” despite the hysterics from some uninformed people. The bolt-action AR-5 was Stoner’s first major firearms accomplishment. The rifle was eventually upgraded to the semi-automatic AR-7, which is currently produced by Henry Repeating Arms.

But Stoner wasn’t done. In 1956, Armalite entered his AR-10 design in the Army’s M-14 trials. Chambered for the 7.62×51 cartridge, the AR-10 was revolutionary. Stoner’s rifle used a direct impingement gas system to operate the action, offering a simple, clean design. The AR-10 was significantly lighter and shorter than its competition and had ergonomic advantages like a pistol grip and easily operated controls. However, the AR-10 had some teething problems and lost out to the Springfield Armory T-44 rifle.

The radical new design showed promise, however, and drew the attention of General Willard Wyman, Commanding General of the Army’s Continental Army Command. Wyman visited Stoner in 1957, encouraging him to continue his work, but with the lighter AR-15 rifle then under development. Wyman even requested that the T-44’s adoption be delayed for the AR-15. He was denied, but 4-star generals carry some weight, and Wyman procured ten AR-15s for testing in 1958.

From AR-15 to M-16

The Army bureaucracy didn’t want Stoner’s rifle. The deliberate sabotage of the M-16 project is an article unto itself. 1958 tests saw production-grade ARs pitted against handmade match-grade M-14s. Stoner was told how poorly his rifles were faring against the M-14 and flew to the Alaskan test site. He found that the sights had been removed and replaced by welding rods. They were not properly zeroed. Of course, no one knew how that had happened. The official report stated that the AR-15 “had not demonstrated sufficient technical merit and should not be deployed by the Army.”

However, the field results were drastically different. A 1959 report from the Army’s Combat Developments Experimentation Center recounted the AR-15’s resounding success in simulated battlefield trials and even recommended early replacement of the M-14 by the new rifle. Army Chief of Staff General Maxwell Taylor declined the recommendation.

The Air Force got involved in 1960, when Assistant Chief of Staff General Curtis LeMay was at a July 4th gathering at Colt Firearms, which had purchased the AR-15’s manufacturing rights. LeMay was a known firearms enthusiast, so Colt officials set up a demonstration. An M-14 and an AR-15 were fired at watermelons. The AR and its .223 cartridge were far more impressive than the M-14. LeMay was impressed and decided the AR-15 was perfect for guarding Air Force installations.

LeMay was promoted to Air Force Chief of Staff in 1961 and adopted the new rifle in January 1962, ordering 80,000 units over the next five years. The Pentagon, led by the Army, objected. They wanted a single, large-bore rifle across all services. The House of Representatives and President Kennedy got involved, influenced by Taylor. However, LeMay eventually won Congress over, and the Air Force got its rifles in May 1962.

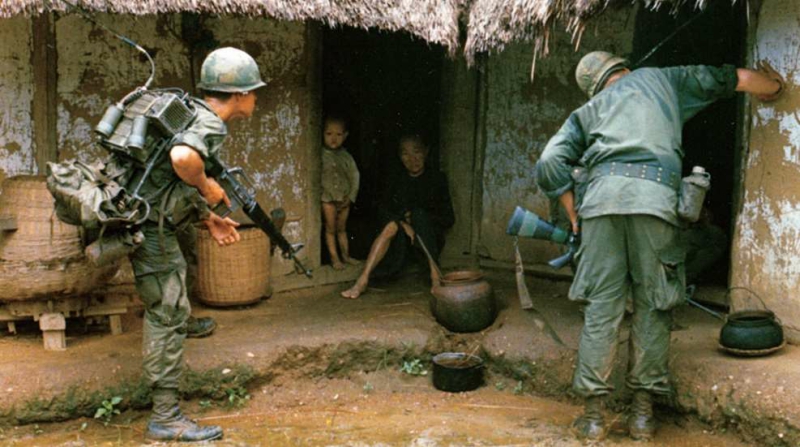

The Army was finally forced to take notice when 1,000 select fire AR-15s were shipped to South Vietnam in 1962. The rifles were issued to ARVN (Army of the Republic of Vietnam) Rangers and US Special Forces advisors for use against the Viet Cong. The soldiers raved about the new rifle and its .223 ammunition. It was light, handy, extremely reliable, and very effective.

The Army didn’t like it, but the ARs had been sent to South Vietnam by Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, who was getting tired of the bureaucratic infighting. McNamara read the glowing reports, as well as the field evaluations of the AR-15 versus the M-14 and, more importantly, the AK-47. Those reports made it clear that the AK completely outclassed the M-14 in Vietnam while the AR-15 more than held its own.

The M-14 was not only inferior to the AK in close combat, but it also had inherent problems of its own. The wood stocks tended to swell in the wet, humid jungle. Worse still, the M-14 was all but uncontrollable in automatic mode. The goal had been to provide infantrymen with an effective select-fire weapon, but the M-14 was failing miserably. Not to mention that soldiers could carry three times as much .223 ammo as they could 7.62×51. That’s a real bonus for a select fire rifle.

McNamara recommended that the 1964 defense budget include 50,000 to 100,000 AR-15s for Special Forces, Airborne, and Airmobile units while continuing M-14 production for infantry units. In mid-1963, McNamara changed that directive, halting M-14 production and adopting the select-fire (non-civilian version) AR-15 as the M-16 for all services. He directly ordered all services to comply. But the Army wasn’t done.

The Right Way and the Army Way

The AR-15 performed well in honest tests, including actual combat in Vietnam. Those ARs were built to Eugene Stoner’s specifications. But now that Stoner’s rifle had been foisted upon them, the Army tossed those tests out the window and sought to bend the AR to fit its own bureaucratic vision.

The details are well-documented. Perhaps most famously, the Army command insisted that Stoner add a forward assist. Never mind that the rifle didn’t need one, based on its performance thus far. Even Stoner pointed out that tamping a jammed round further into the chamber made no sense at all. But the M-1 Garand, M-1 Carbine, and M-14 all had one, so the command felt that soldiers would feel better about the transition. Not kidding. The new model was designated the XM-16E1.

The other changes were more serious and ultimately cost many soldiers and Marines their lives. The Army contracting procedure caused them to change the .223 Remington’s original powder to one that increased the round’s velocity. That significantly increased the rifle’s fire rate, causing major fouling in the chamber and gas system where none had been before. The gas system couldn’t keep up with the higher cyclic rate, allowing residue into the gas tube. The M-16 went from a supremely reliable weapon to one of the worst battlefield screw-ups in American military history.

Colt’s testing experienced such high failure rates that the company requested their production rifles be tested with the powder of their choosing. They went with the original. But those same rifles went to Vietnam with the Army’s chosen ammo, which caused the fouling. Colt and/or the Army also billed the M-16 as being “self-cleaning,” telling soldiers they didn’t have to maintain it. I haven’t been able to determine whose bright idea that was. Some say it was Colt; some say it was the Army. Maybe it was both. It didn’t help that the chambers and barrels weren’t chrome-lined because it was deemed too expensive. The rifles shipped without cleaning kits, though soldiers occasionally scrounged one. But most men never even saw a cleaning kit until at least 1968.

Either way, from late 1965 into early 1969, American soldiers and Marines experienced catastrophic fouling that they could not clear in the field. Countless men were found dead with their disassembled rifles beside them. One soldier was killed while running between his squad mates and using their only cleaning rod to punch out jammed rounds. The Army, which oversaw weapons development, did nothing. They blamed it on poor field maintenance. It wasn’t intentional, but the bureaucrats could not see or admit their chain of mistakes.

Only when men began writing to their families and their congressmen about the problems was something done. A special House committee investigated and forced the Army to act. The problems were largely solved by mid-1969, but the M-16, and by extension, the AR-15, has been dogged by the “unreliable” label ever since. I was unable to find a number for how many men were killed, at least partially because their rifles failed in close combat. All thanks to Army bureaucracy.

I should note that the Army got its way in the end. The buffer spring and twist rate were adjusted in 1969’s M-16A1 to reliably achieve the Army’s target muzzle velocity. The Army’s only reason for their preferred 3,250 fps velocity was basically, “That’s what we want.” It was a purely arbitrary number based on the 7.62×51 NATO round. The original .223 ammo delivered about 3,150 fps. So, the whole system was changed for an extra 100fps. But even though the M-16 worked again, it never matched Stoner’s original performance profile since the specs were changed and the .223 round was rendered less effective thanks to increased stability. Again, Army bureaucracy.

The M-16: A Legacy of Success

Eugene Stoner’s rifle has been an unmitigated success. I can say that because I refuse to attribute the Army’s XM-16E1 to Stoner. The M-16A1 didn’t return the rifle to its inventor’s vision, but that rifle and its descendants work, and they work very well. The M-16A1 became more versatile via its compatibility with the M-203 grenade launcher. Vietnam-era Special Forces units were often issued shorter XM-177s and GAU-5s (Air Force designation), both M-16 derivatives based on the Colt Commando, also known as the CAR-15.

The M-16A1 gave way to the Marine Corps’ upgraded M-16A2 in the early 1980s. The Army adopted it a few years later. The 5.56 NATO round grew from the .223 Remington, becoming the standard NATO cartridge in 1980, despite the modern round not being as potent when paired with the current spec rifles.

The M-16A3 and M-16A4 followed, each iteration providing more modern features. The carry handle became removable for optics. Brass deflectors and easier controls became the norm. The somewhat controversial burst-fire option became a thing with the A2. The M-4 and M-4A1 Carbine eventually succeeded its parent as the US military’s standard-issue small arm, featuring all the M-16’s advances in a shorter, lighter, more versatile service rifle. The M-16 and M-4 would not have lasted this long were they not excellent weapons systems.

But time passes, and requirements change. The M-16/M-4 was recently succeeded by the Sig XM-7 rifles chambered in 6.8x51mm (.277 Sig Fury). Only time will tell how that will go. The XM-7 may be a resounding success, and I hope it is for many reasons. But it will be difficult to match the rifle designed by a self-taught aircraft ordnance engineer. I guess we can check back in 60 years and find out.