Some say that big things come in small packages. That saying holds true for the .22 Short. The Short is the smallest and least powerful ammunition you are likely to find on the shelf today. It uses a light 27–29-grain bullet and less than a half-inch worth of case length for powder. Although the Short now lives in the long shadow of the more popular .22 Long Rifle round, the parent did and can do many of the things the child does. And it did it first! Follow along as we explore the history and ballistics of the .22 Short.

The .22 Short: A Short History

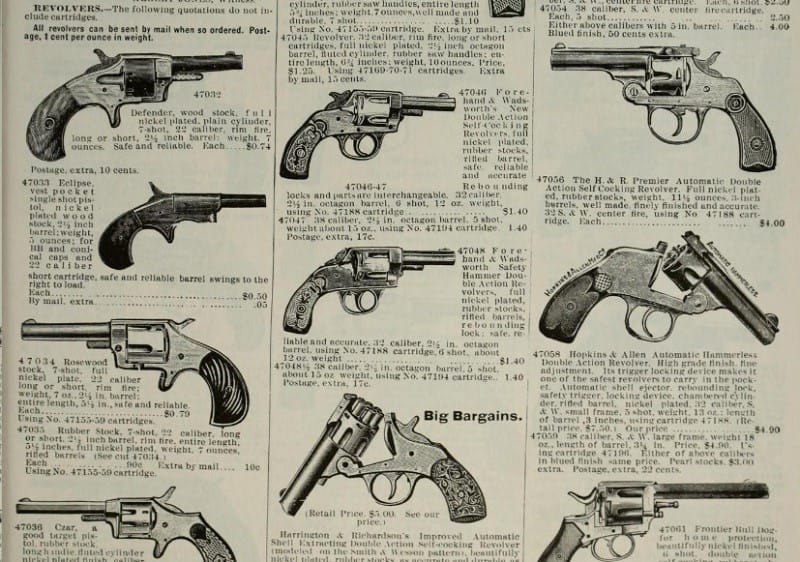

The .22 Short has the distinction of being the first modern self-contained cartridge. It was introduced in 1857 for the Smith & Wesson No. 1 revolver. The No. 1 is the first production firearm with a bored-through chamber that allowed loading from the rear instead of the front like a muzzleloader. The cartridge era quietly arrived a decade before popular histories will tell you, but it did so with a fizz rather than a bang.

The .22 Short shares an origin story with rounds like the .22 Flobert, which was essentially an elongated percussion cap topped with a lead BB and no gunpowder. That round was popular for indoor target practice but did not have much practical utility. The .22 Short has a longer rimfire case that is .42 inches long. That gave just enough room for four grains of black powder and a 29-grain lead bullet. It left a revolver’s barrel at under 600 feet per second.

The Modern .22 Short

But time never stands still and manufacturers were always keen to increase the effectiveness of the .22 Short. The answer was to increase the bullet weight and the length of the case. There was the .22 Long, the .22 Extra Long, and finally the .22 Long Rifle. The latter round shot a 40-grain bullet at 1,080 feet per second and it was improved further in 1930 with the high-velocity Remington Hi-Speed load, which boosted velocity to 1,280 feet per second. The .22 Short could rival standard velocity .22 LR in speed out of a rifle barrel, but it did so with a lighter bullet.

By the 1930s, the .22 LR had taken over the rimfire rifle scene. But the .22 Short retained its niche in the pistol market. Target shooters preferred the Short for its inherent short-range accuracy. The short case length also made it ideal for producing very small revolvers and autoloaders.

Pocket pistols like the Beretta Minx were available until very recently in either .25 ACP or .22 Short, not .22 LR. .22 Short-only rifles are mostly elderly designs with some exceptions. The Browning SA 22 was available in .22 Short until it was discontinued in that caliber in 2017. However, the .22 LR is simply a longer version of the Short, so you can fire .22 Short in a .22 LR chamber. The weaker round will not cycle in an autoloading rifle chambered in .22 LR but they will generally feed and cycle in manually operated rifles. Some rifles made today are still marked .22 S/L/LR, denoting that the rifle will feed and shoot either .22 Short, .22 Long, and .22 LR. But in an era where .22 LR is king, why bother with .22 Shorts?

Where .22 Short Beats .22 LR

The .22 LR has several advantages over the .22 Short. There are more .22 LR loads on the market and the ammunition is usually less expensive and more available than .22 Short. The .22 LR is available in a wider variety of rifles and handguns today. .22 Long Rifle ammunition will generally produce higher muzzle velocity and use heavier bullets, producing less drop and wind drift as well as somewhat more power downrange. Very few .22 Short-only firearms are made now, and the round is normally used in guns bored in .22 LR. But why bother with having some .22 Short ammunition handy?

One of the reasons I initially gravitated to .22 Short ammunition is its low noise and no flash. While high-velocity loadings of both the .22 LR and .22 Short both break the sound barrier, the hard crack of the .22 LR is not present with the Short. The small powder load of the Short is also burned up completely, so there is less flash and noise from powder burning beyond the muzzle. Unlike .22 LR subsonic loads, the .22 Short CB is Hollywood-quiet without the need for a suppressor. The CB Short has an advertised rifle velocity of 710 feet per second. The .22 Short can be used to dispatch pests or for target practice in areas where the crack of even a .22 LR might invite unwanted scrutiny.

In some rifles, the .22 Short also increases magazine capacity. In tubular magazine-fed rifles, the Short is shorter, so you can fit more of them in the tube. When using my Henry Small Game Carbine, I can fit 16 Shorts whereas it only holds a dozen rounds of .22 LR. Will that make a material difference in any sort of shooting? Probably not. But if you are looking for more smiles per round or need fewer reloads, the Short is worth considering.

The Ballistics and Power of the .22 Short

While I am not one to smile, I consider myself an optimist in the sense that I like to make a case for a cartridge no matter how small or obscure it is. That includes the .22 Short. The .22 CB Short is still my go-to round for discreet pest control on anything up to the size of an armadillo. I also reckon that high-velocity Shorts are downright fun to shoot and do less meat damage on game animals compared to the .22 LR. But my use of the .22 Short is purely driven by experience, not data that can be compared to its bigger brother.

To leave no round unloved, I brought a box of CCI 27-grain HV Shorts to run through two of my favorite .22 firearms: a CZ 457 Scout rifle and a Ruger Single Six revolver.

I had never shot .22 Short beyond short distances of no more than 30 yards, so I decided to check the ballistic drop of the .22 Short relative to .22 LR. I benched the CZ 457 and fired five rounds at a 50-yard target to confirm my zero using CCI Blazer .22 LR 40-grain high-velocity loads. Later, I switched to the Shorts and repeated the same practice.

The .22 LR rounds printed .5-inch higher than the aiming point at 25 yards and dead on at 50 yards. The .22 Shorts printed at the aiming point at 25 yards but two inches low at 50 yards.

The trajectory of the .22 Short is more elliptical but still useful. But what about the power of each round? To that end, I started by shooting the HV Shorts over my Caldwell Chronograph from both the rifle and handgun at a distance of ten feet. The 16-inch barreled CZ produced a five-shot average velocity of 1,181 feet per second, while the 5.5-inch barreled Ruger Single Six pushed them out at 1,057 feet per second. The advertised muzzle velocity of these rounds is 1,105 feet per second. On previous occasions, the CCI Blazer .22 LR load was measured at 1,187 feet per second using the rifle and 1,108 with the revolver.

Velocity Differences

In terms of initial velocity, there is little difference to talk about. But how much damage will that lighter 27-grain bullet do compared to a 40-grain .22 LR? To test that, I set up two bare 10% Clear Ballistic gel blocks and fired two rounds from the rifle and two from the pistol. I shot the blocks at a distance of 25 yards with the rifle and 10 feet with the pistol.

One projectile fired from the rifle tumbled and stopped short at 10.25 inches of penetration. The second rifle round and both pistol rounds landed right at the twelve-inch mark. Although the .22 Short loads used are hollow points, there was no expansion.

In recent tests in the same medium, using the same firearms at the same distances, I could get the .22 LR CCI Blazer load to 11 inches of penetration out of the revolver and 13 inches out of the rifle. The difference lay in the amount of damage to the target. The .22 Short, whether fired from the rifle or pistol, produced narrow and straight wound tracts. The .22 LR’s longer bullet tends to tumble, producing more substantial wounds both in gelatin and in larger targets. Depending on what you are shooting, you may or may not want that damage. Because when it comes to pushing bullets deep, it is either round’s game—at least at closer distances.

The .22 Short: Outmoded, Not Outdone

The .22 Short gets the honor of being the first metallic cartridge in the United States and one that set the pace for what we have today. In its day, the .22 Short kept meat on the table and predators of all stripes at bay. But by all accounts, the Short should have died quietly long ago. The .22 LR muscled the Short out of the rifle and handgun world. It is generally more powerful and more available. But the .22 Short is still with us. Certainly, the .22 Short is around partially because of the vast number of old guns that only shoot .22 Short. Entire cartridge lines like .25 ACP, and .32 S&W are still being made simply because millions of guns were made for them. But I am not convinced this dwindling demand is enough. Unlike those other cartridges, there are other reasons to grab a box of Shorts. Whether you need a quieter round that solves your pest problems, less damaging rounds for small-game hunting applications, or simply plinking away on the weekend, you might consider some loading of the .22 Short. And if our little range experiment says anything, the .22 Short may be outmoded but never quite outdone.