A hush falls over the street as the two men walk out to face one another. Anxious eyes watch from behind drawn curtains or through cracked doorways. The men stop 75 feet apart, pulling their dusters back, revealing low-slung Colt six-shooters. The tension mounts as squinted eyes stare through the noontime sunlight. Fingers tap the ivory or hardwood pistol grips. A tumbleweed blows past. A flash of motion, the Colt seemingly magically appearing in a hand, but not fast enough. His adversary’s lightning draw was even quicker, the off hand fanning the hammer as the gun comes up. The bad guy falls, disbelief in his eyes as he breathes his last, bleeding out in the dirt street.

Myth or Reality?

It’s a familiar scene of which television and movie fans seemingly never tire. From silent movies to “Star Wars,” the Old West gunfighter trope is one of Hollywood’s most prominent and reliable. That’s because it works. It’s also almost entirely a myth. Real-life gunslingers, or “Shootists,” as some thought of themselves, rarely fought fair.

Most gunfights were alcohol-fueled arguments gone bad, often over the ubiquitous card games in Old West saloons. Many accomplished shootists made their living gambling, and cheating could carry a death sentence. Many also had volatile personalities that were enhanced by drinking. Encounters were sudden and savage, usually at very close range. There was often no discernable “good guy,” even when lawmen were involved.

The shootists themselves often flitted back and forth over the line delineating good and bad. Many questionable types became sheriffs or marshals since the rowdy frontier cattle towns like Dodge City or Abilene needed their particular skill set to control drunken cowboys fresh from a cattle drive. Predictably, many eventually fell back to their old ways, often due to drunkenness.

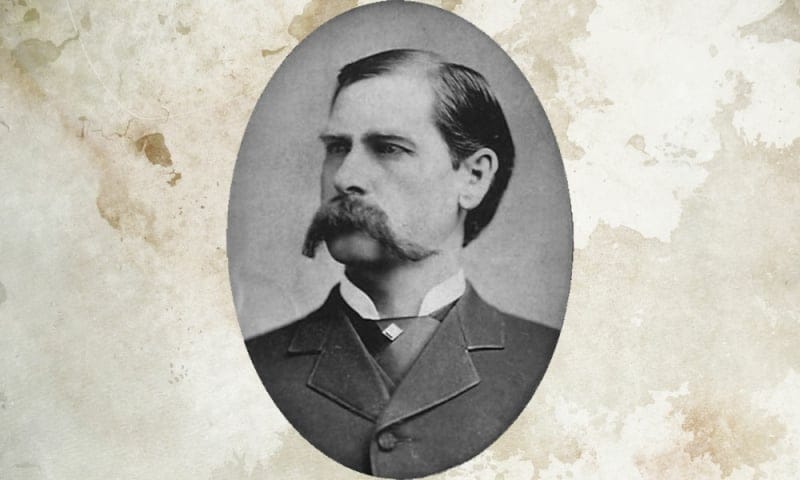

Even career lawmen like Virgil Earp sometimes found themselves facing charges brought by corrupt local governments. Virgil’s more well-known brother, Wyatt, often skirted the law, despite being perhaps the most famous peace officer of the time. Wyatt Earp is partially responsible for the gunslinger mythology. He later served as a technical advisor on silent-era Westerns that established today’s familiar tropes. Two early Western stars, Tom Mix and William S. Hart, served as pallbearers at his 1929 funeral.

To be fair, famous “gunslingers” could make some easy money by telling their stories to Eastern journalists and dime store novelists. The more outrageous the story, the more the Eastern public ate it up. Wild Bill Hickok may have started the trend in 1867 when he told a reporter that he had personally killed over 100 men. The reporter, of course, took him at his word and repeated Hickok’s claim in the New York Herald. Hickok became an instant celebrity. Hickok, in reality, seems to have killed eight men, though his count stood at a comparatively modest four when he talked to the reporter (I should note that the total does not include Hickok’s accidental killing of Deputy Mike Williams in 1871). But the claim, and lack of official response, shows how lawless the West truly was at the time.

Some, like John Wesley Hardin, wrote the books themselves. Hardin’s autobiography, however, while embellished, was not as sensational as most accounts written by Eastern authors. Perhaps that’s because Hardin’s short career needed no exaggeration. Here’s a look at just a few of these men and how they fought.

Wild Bill Hickok

Hickok, despite the inflated body count, was one of the few whose gun skills were on par with his reputation. He reportedly killed David McCanles in a property dispute from 75 yards away with his single action revolver. Hickok was also one of the very few who engaged in something approaching the stereotypical Wild West gunfight.

As sheriff of Hays City, Kansas in 1869, he killed two men causing disturbances. He is said to have given both men a chance to defend themselves. Hickok killed another man a year later, when drunken soldiers from the 7th US Cavalry caught him off guard, knocked him to the floor, and began kicking him. Hickok drew his pistols and fired, killing one soldier and gravely wounding another.

Wild Bill’s final kill came in 1871, when, as Marshal, he confronted cowboy Phil Coe about discharging his gun in town. Coe, who was drunk, had shot at a dog he thought was attacking him. Hickok told Coe that guns were not allowed in the city limits, whereupon Coe fired at him. Hickok responded by shooting Coe twice in the stomach.

Deputy Mike Williams came running up behind Hickok to help. Hearing the running footsteps, Wild Bill whirled and fired, killing Williams. No charges were filed against Hickok due to the fluid situation and the accidental nature of Williams’ death. Given Abilene’s atmosphere in 1871, it seemed reasonable that Hickok should believe he was being attacked from behind.

John Wesley Hardin

Texan John Wesley Hardin was another skilled gunman and may have been the closest thing to the stereotypical Western outlaw. The son of a Methodist preacher, Hardin killed his first man at age 15 when he gunned down a former slave, armed with a wooden club, whom a friend had beaten in a wrestling match. Hardin rode eight miles to get medical help, but the man died a few days later. Hardin ran, knowing he’d be charged with murder. It was the Reconstruction era and Union troops were still in Texas. Not long after, he ambushed and killed the Union soldiers sent to capture him.

Hardin went on to kill as many as 42 men, though the accounts vary wildly, with some saying he killed as few as eight. Most of those were Hardin getting the drop on his victims, as he was known to be constantly looking for advantages, even down to carrying his two revolvers in chest holsters for a faster draw. The low-slung thigh holsters are pure Hollywood.

Hardin was reportedly as fast and accurate as Hickok and the 1871 encounter between the two, in Abilene, is fraught with inconsistencies. According to some, the 18-year-old Hardin got the drop on Hickok by appearing to surrender his pistols, then spinning them at the last second. Hickok supposedly calmly talked the younger man down by offering to be his friend.

Others say the story is preposterous. Hickok, they say, would never have allowed his reputation to take such a hit, and would have been wary of such a move in the first place, since it was a common trick shooter stunt. But, whatever the truth, it does seem that Hickok and Hardin were friendly for a short time.

According to Hardin, that ended when he was awakened one night by a man snoring in the hotel room next to his. The details are disputed, but Hardin fired through the wall (some say ceiling) and killed the man. Knowing Hickok would soon arrive, Hardin fled through his window in only his underclothes, not willing to face Wild Bill. Even though Hardin himself tells this story, others dispute the claim. But it does seem like Hardin was wary of a hostile Hickok.

Clay Allison

New Mexico’s Clay Allison was once asked what he did for a living. “I am a shootist,” he replied. Whether Allison coined the term or not, the claim was accurate, though he was as deadly with a knife as he was with a gun. Allison once settled a dispute over a Texas water hole by digging a shallow grave within which he and his rival fought with Bowie Knives. The winner got the water hole, and the loser got the grave. Allison got the water hole.

A later incident saw a drunken Allison throw knives at two men who angered him, pinning them to the wall by their shirt sleeves. He also sought revenge on a dentist who pulled the wrong tooth by holding the man down and extracting a molar with a pair of forceps. The man’s screams attracted a crowd, stopping Allison from pulling another.

Allison was famous for his quick draw, which he claimed was faster than Hickok’s. A gunman named Chunk Colbert decided to try Allison one night in 1874. Colbert reportedly bragged that he had killed six men in Texas and that Allison would be the seventh. Some say Colbert wanted revenge for his uncle, a ferryman Allison had severely beaten several years previously. The two men spent the day drinking and gambling together, after which Colbert invited Allison to a nearby restaurant.

Allison laid his revolver on the table while he ate. Suddenly, Colbert drew his revolver from under the table, but snagged the muzzle on the table’s edge, deflecting his shot. Allison shot Colbert in the head, killing him. Allison had apparently gotten word that Colbert was gunning for him and waited for the other man to make a move. Asked why he accepted Colbert’s hospitality, Allison said, “Because I didn’t want to send a man to Hell on an empty stomach.”

It should be noted that Allison seems to have suffered from a brain injury inflicted in his youth, which led to wild mood swings and frequent bursts of anger. This was given as the reason for his discharge from the Confederate Army in 1862. He soon joined Nathan Bedford Forrest’s Confederate Cavalry, where he served the rest of the war. He also drank heavily, which likely made his emotional problems worse.

Doc Holliday

Perhaps no man exemplified the volatile mix of alcohol and the willingness to visit violence than John Henry “Doc” Holliday. Holliday is well-known as Wyatt Earp’s best friend and deadliest associate. A licensed dentist, “Doc” Holliday was afflicted by tuberculosis, meaning he coughed constantly. Few patients want their dentists coughing in their face, or while engaging in a delicate procedure, so Holliday’s dental career bore little fruit. His physician recommended moving to a drier environment than his native Georgia, which Holliday did, hoping it would ease his ailment.

Sickly and thin, Holliday weighed only about 130 pounds, despite being 5’10”. This, according to famed lawman Bat Masterson, who knew him and wrote about him later in life. Masterson wrote that Holliday was so physically weak that he “could not have whipped a healthy 15-year-old boy in a go-as-you-please fist fight, and no one knew this better than himself.” Masterson claimed this knowledge motivated Holliday’s quick resort to weapons when he felt threatened. Given Holliday’s history, this was quite often, especially as Masterton described Doc as “hot-headed and impetuous and very much given to both drinking and quarreling.”

This was evident in an 1877 encounter with a local bully named Ed Bailey in Fort Griffin, Texas. Doc had taken to carrying a wicked long-bladed knife in addition to his two revolvers. Bailey overtly cheated at cards, even after Holliday warned him twice. After the third time, Doc laid down his cards and pulled the pot in for himself. Bailey reached for his pistol, but the lightning-quick Holliday pulled the knife and gutted the other man before he could fire. Bailey bled out on the table. Despite acting in self-defense, a vigilante mob came after Doc, prompting him and his erstwhile paramour Big Nose Kate to flee to Dodge City.

Holliday was every bit the deadly gunman he is portrayed as in the movies, but it was his quick resort to violence that gave him the edge, as opposed to superior skills. Doc killed without warning, having no compunction about his actions. As a result, he was constantly on the move between Texas, Colorado, Kansas, and Arizona.

Wyatt Earp’s devotion to Holliday came about when Doc got the drop on some drunken cowboys who, in turn, had Earp dead to rights in Dodge City’s Long Branch Saloon. Earp and Holliday had hit it off a few years previously in Fort Griffin when Doc gave Earp information leading to a wanted outlaw’s arrest. Their friendship lasted until Doc’s death, and the only place Holliday stayed out of trouble was Dodge City when Earp was marshal there. Their exploits together in Tombstone, Arizona are well known.

Who Killed Ringo?

One other incident bears mentioning, if only because of Hollywood. The movie “Tombstone” plays up a rivalry between Doc and outlaw Johnny Ringo. Doc kills Ringo in a classic showdown at the end. The real Ringo was found dead of a gunshot wound to the head shortly after Earp’s “Vendetta Ride” against the men who murdered his brother Morgan. Ringo’s body was lying under a tree, his six-shooter beside him in the grass.

Many say that Ringo suffered from acute depression and likely killed himself. This explanation seems to have credence since Holliday and Earp were both in Colorado at the time. Except others claim that Earp and Holliday secretly went back to Tombstone about this time and killed Ringo. Those same people claim that Ringo’s revolver still had six rounds in the chamber. There’s really no way to know. For all we know, Ringo’s gun had five cartridges and one spent case. Ringo is buried on the spot. Dead men tell no tales, I guess. Earp later claimed he killed Ringo, but eventually recanted. What is likely though, is that if Earp and Holliday killed Ringo, it was probably an ambush and not the face-off portrayed in the movie.

Blurred Lines

Despite the movies, the Wild West’s gunslingers had little sense of honor. They killed quickly and with whatever advantage they could gain. They were often drunk. They benefited from underdeveloped legal systems lacking the means or resources to track them down. Even the lawmen themselves hampered the system. Bat Masterson writes of inventing a robbery charge against Holliday in Colorado to thwart Doc’s being extradited to Arizona after Earp’s vendetta.

The Earps themselves were charged after the OK Corral but nothing happened to them. To be fair, Tombstone Sheriff John Behan was firmly in the Clanton gang’s pocket. Hickok once killed a man in 1865 who was wearing the pocket watch he had won from Wild Bill the night before. Hickok was acquitted. Gunmen were quick to claim self-defense, and local judges and juries often saw it that way too.

The line between law and outlaw was often blurry, with men such as Wyatt Earp, Hickok, and Masterson walking both sides in a volatile world of violent men. Dallas Stoudenmire killed several men before becoming a Texas Ranger and then the marshal who cleaned up El Paso, Texas for a time.

While marshal, Stoudenmire was involved in the famous “Four Dead in Five Seconds” gunfight. Stoudenmire himself accidentally shot and killed a Mexican bystander during the incident. He also killed a man who was retreating with his hands up. No charges were proffered. The gunfight was sparked when an El Paso Constable began arguing with a former El Paso Marshal.

Stoudenmire was a hard drinker and was eventually killed in a long-running feud between himself and a local family of corrupt politicians. They were signing a peace treaty proposed by city residents when they began arguing and started shooting. His killers, James and Doc Manning, were acquitted on a self-defense claim. Doc Manning had pistol-whipped Stoudenmire’s corpse after the killing.

Not the Movies

I love the great Western tropes. I love the showdowns between good guys and bad. I love Josey Wales facing down the bounty hunter; Doc Holliday saying “I’m your Huckleberry;” the Duke; and Trinity slapping the bad guy’s face between draws. I love Marty Robbins’ Arizona Ranger taking down Texas Red in “Big Iron.” I also love how great movies like “Unforgiven” fudge that line between good and bad. Those might be the closest thing to real Old West gunfighters, though it’s still just entertainment.

Most of those men lived short, brutal lives, even those who weren’t killed by another man’s bullet. Doc Holliday spent the last 57 days of his life in a Glenwood Springs, Colorado hospital bed, dying of tuberculosis. He awoke, asked for a glass of whiskey, and after taking a drink, looked at his bare feet and said, “This is funny.” Then he died. We don’t know how many men Holliday killed, but they were never in fair fights. It’s said that only a fool fights fairly. Holliday and his contemporaries were nobody’s fools.

Prominent Old West historian Kathy Alexander notes that Holliday was supposed to be interred in the local cemetery, but the icy road precluded hauling his body up the hill. He was buried at the foot of the hill, with plans to move his body after the spring thaw. That never happened. The cemetery marker bearing his name presides over an empty grave. A housing development later grew up around the hill. Doc Holliday is likely buried in someone’s backyard, something he may well find funny, wherever he is.