February 9, 1943. Two columns of US Marines and US Army soldiers met at Tenaro Village on Guadalcanal’s northwest coast. The wrecked remains of the Japanese Guadalcanal force were all around them. Wasted bodies of dead soldiers lay where they fell. Burned out ships and boats littered the shore. Ruined equipment littered the ground. The few surviving Japanese were so far gone from hunger and disease that their evacuating comrades left them behind.

Later that day, General Alexander Patch, the US commander on Guadalcanal, radioed his boss, Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey, “Total and complete defeat of Japanese forces on Guadalcanal effected 16:25 today…the Tokyo Express no longer has a terminus on Guadalcanal.” Six months and two days after the First Marine Division landed, “the ‘Canal” was finally secure and the Japanese Empire’s days were numbered.

Midway or Guadalcanal?

Guadalcanal’s importance is often misunderstood. It was the first American offensive of World War II. The first step on the long road to Tokyo Bay. But the spectacular June 1942 naval victory at Midway long overshadowed the Guadalcanal Campaign’s grinding attrition as the Pacific War’s turning point. It’s understandable. Japan lost four of her best aircraft carriers and all their aircraft at Midway. How could such a one-sided victory not be the war’s turning point?

Despite the Midway losses, Japan’s carrier forces outnumbered the US Navy’s into 1943. Most of the superb Japanese pilots and aircrew survived Midway and their aircraft were superior to their American counterparts. Japanese surface forces outnumbered the US Pacific Fleet. Their crews were better trained, especially in night fighting.

Time has shown that Midway wrested away Japan’s strategic initiative, balancing that all-important force until one side or the other tipped it in their favor. Japan had to reassess and reallocate after Midway, while the United States was hamstrung by the Allies’ “Germany first” policy. Whichever side struck first would likely swing the hanging pendulum in their favor.

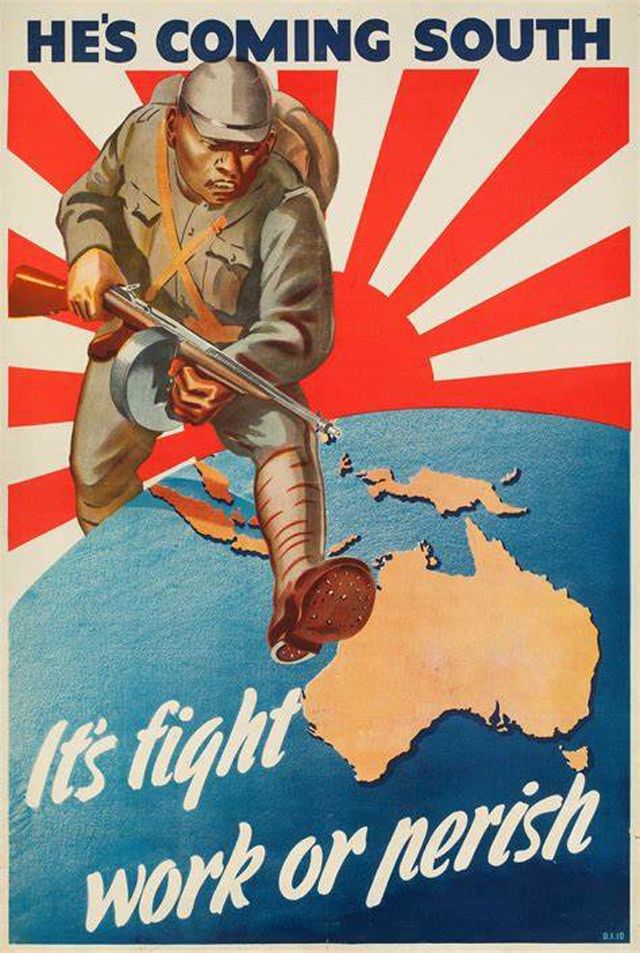

US Navy chief Admiral Ernest J. King sensed the shift and pushed for a Pacific offensive for months before an opportunity fell into his lap in July 1942. A British colonial official turned South Pacific coast watcher named Martin Clemens reported the construction of a Japanese airfield on Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands. When completed, the airfield would allow Japanese aircraft to range deep into the Coral Sea, threatening Australia’s American lifeline. It could also support forward naval operations aimed at Samoa and Fiji.

King alerted US Pacific Fleet commander, Admiral Chester Nimitz, to ready his command for a Solomons operation commencing August 1st. The preparations for Guadalcanal are a story unto themselves, but King got his way. American naval guns opened up on Guadalcanal’s northwestern beaches at 6:13 AM on August 7, 1942. Around 8 AM, elements of the First Marine Division stepped ashore unopposed.

Twenty miles north and thirty minutes earlier, across the sound, their fellow Marines stormed the beach on Tulagi, a small island that had served as the British colonial seat. Japanese naval troops fought hard but were overwhelmed in a couple days. Tulagi was the first small victory in the Solomons, a campaign that would be called “the graveyard of the Japanese Army.”

Guadalcanal: A Three-Dimensional Campaign

Though Guadalcanal is a single island, its conquest required a true campaign on land, on the sea, and in the air. Had one leg of that triad faltered, the entire enterprise would have collapsed. There were no forward American bases to directly support the men in the combat zone. The Marines on Guadalcanal relied on slapped-together air and seaborne logistical systems just to keep fighting. Even when supplies came in, strong Japanese naval and air assets harassed the operations. Transport ships spent as much time dodging Japanese bombs as they did unloading men and supplies.

Once the Marines established a defensive perimeter ashore, they raced to complete the Japanese airfield. The landings were supported by three American aircraft carriers, but the task force commander, Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher, flatly refused to keep his carriers on station longer than two days, despite knowing the transports required four days to unload. As it turned out, Fletcher left after only thirty-six hours.

Thus began the deadly race to see which side could build up its forces to kick the other off the island. The Marines needed air cover and regular resupply. Completing the airfield, which they named Henderson Field after Major Lofton Henderson, a Marine pilot killed at Midway, gave the Americans their air cover when Navy and Marine aircraft arrived on August 20. But constant Japanese air raids meant that planes and pilots had to be constantly replenished.

The Japanese also regularly sent warships down “the Slot” to bombard Henderson Field at night. Heavy naval shells destroyed aircraft and facilities, killed men, and frazzled those they didn’t kill. A systematic resupply effort nicknamed “the Tokyo Express” by the Americans, fed Japanese troops and equipment onto the island. The US Navy fought eight major engagements during the campaign, but they couldn’t stay on station all, or even most of the time. At one point, the Pacific Fleet was reduced to just one aircraft carrier, the Enterprise, which could not risk staying in one place too long.

“Operation Watchtower” was the official name for the Guadalcanal landing, but the precarious logistical situation and the back-and-forth naval battles caused the Marines to dub it “Operation Shoestring.”

Jungle Fighting

The Tenaru River

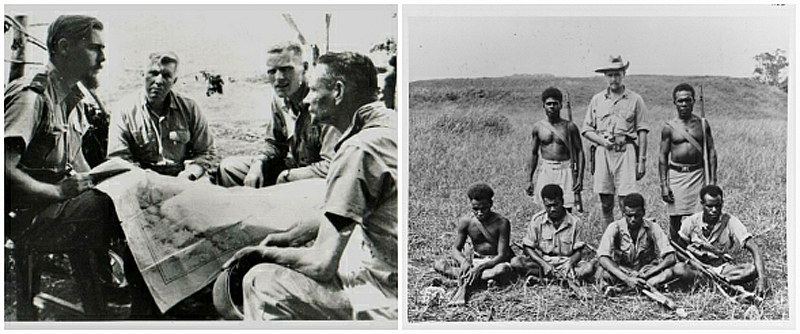

The Japanese wasted no time in moving troops to expel the Marines. Japanese ships were heard off the coast on the night of August 18. The next day, Clemens, who had joined the Marines after they landed, heard from his native contacts that a large Japanese force had landed east of the American perimeter. He dispatched a native scout, a Colonial Constable named Jacob Vouza, to recon the area.

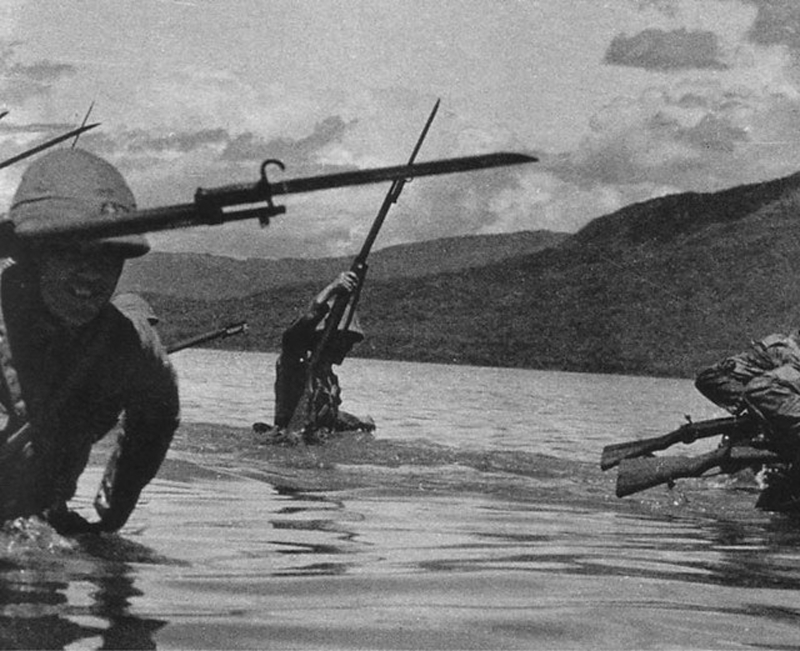

First Marine Division commander Major General A.A. Vandegrift strengthened his line on the west bank of the Tenaru River, just east of the airfield. At 2:30 AM the next morning, screams of “Banzai!” tore through the night and the Japanese opened up from the river’s east bank. The Marines returned fire, but a column of Japanese soldiers stormed across a sandbar at the river’s mouth. They got tangled up in the Marines’ barbed wire defenses, where withering machine gun, mortar, and rifle fire slaughtered them. A second charge was beaten back shortly thereafter.

Just before dawn, a Marine battalion crossed the river upstream and cornered the 500 Japanese survivors. The next day, Marines, light tanks, and F4F Wildcat fighter planes mopped up what was left. All 800 Japanese soldiers perished. The Marines lost 43 killed and 57 wounded.

While all that was going on, Jacob Vouza crawled back into the American lines. He was nearly dead. Vouza had been captured and tied to a tree and brutally tortured. The Japanese soldiers beat him with rifle butts, and he had multiple bayonet wounds. But Vouza survived and resumed his scouting duties just twelve days later. Despite his ordeal, Vouza gave the Japanese no information. The Americans and British decorated him and Queen Elizabeth Knighted him in 1979. He retired a Sergeant Major.

Bloody Ridge (Edson’s Ridge)

The Japanese kept building up their troop strength by running in fast destroyers at night, unloading, then withdrawing before dawn. The Americans knew what was happening. Air patrols saw the ships coming down from the Northwest, but night air operations were impossible and naval interdiction was sporadic at best.

Expecting an attack, Vandegrift posted Colonel Merritt Edson’s Marine Raider Battalion on the ridge overlooking Henderson Field from the south. Following two days and nights of intense air and naval bombardment, Edson’s men took the brunt of the Japanese attack on the night of September 13.

The fighting quickly devolved into vicious hand-to-hand encounters in the dark. Edson’s men withdrew to a knoll on the ridgeline, pouring machine gun and mortar fire into the charging Japanese soldiers. The Marine Parachute Battalion, held in reserve, then slammed into the Japanese right flank, forcing them back. Marine 105mm howitzers tore into the Japanese force throughout the night.

A few Japanese infiltrators made it through to Henderson Field, where the Marines were waiting with several SBD Dauntless dive bombers turned so their rear .50 caliber machine guns could defend the airstrip. One Marine concealed himself in a plane’s shadow, letting an infiltrator jump onto the wing before emptying his Thompson submachine gun into the man’s chest. Two Japanese soldiers, led by a samurai sword wielding officer, made it to Vandegrift’s command post 300 yards from the ridge. Marines cut them down in sight of the general.

Edson’s battalion held the ridge and morning found the Japanese in retreat. Fighter planes from Henderson Field and Marine patrols took care of the rest. The Japanese lost around 1,200 soldiers. Most of them killed. The Marines lost 143 men killed or wounded.

“The Night”

While the Americans and Japanese constantly skirmished, especially along the Matanikau River west of Henderson Field, the last major Japanese ground attack came in October.

But first, the men endured what survivors called “the Night.” As usual, enemy bombs and artillery harassed the Marines all day and into the night. But at 1:30 AM on October 14, a star shell exploded over Henderson Field. A minute later, a sound like giant freight trains ripped through the night. Titanic explosions rocked the airfield and its environs. The Japanese battleships Kongo and Haruna had arrived and were dropping their 14-inch shells on the Americans from ten miles offshore.

A Navy pilot recalled that “We could see the flash from a salvo light the sky, hear the report, then the whistle of shells, and finally the terrible crack-crack-crack of the shell exploding. Coconut trees split off and crashed to the ground, shrapnel whirred through the air, a few duds came crashing and bounding through the jungle without exploding. When a big one struck, the walls of the dugout trembled the way chocolate pudding does when someone spats it with a spoon.”

The concussion picked men up and slammed them against the walls of their bomb shelters. Colonel Merrill B. Twining said, “the earth seemed to turn to the consistency of Jell-O, making it difficult to move or even remain upright.”

The two battleships expended 500 14-inch shells in an hour and a half. Vandegrift vowed in the aftermath to never judge a man suffering from combat fatigue or shell shock ever again. Despite the strongly built bomb shelters, the shelling killed 41 men. Only a dozen or so aircraft were flyable. Most were a total loss. The shells demolished many of the camp facilities and personnel quarters.

Halsey Takes Command

Mid-October was the low point for the Americans on Guadalcanal. Men started to slip, and the fear of defeat began to creep in. Despite sending the Army’s 164th Infantry Regiment to reinforce the island, South Pacific Theater commander Admiral Robert Ghormley supposedly authorized Vandegrift to surrender, though no such communication has ever been found. The morning of October 15 saw American observers watching six Japanese troop transports unloading ten miles to their west, while enemy destroyers patrolled a mile offshore.

But two days later, morale improved when the Americans heard that Admiral Halsey had relieved the overwhelmed Ghormley. Halsey was a sailor’s sailor. He was blunt, profane, and aggressive. One Navy airman wrote that “One minute, we were too limp with malaria to crawl out of our foxholes; the next, we were running around whooping like kids…If morale had been enough, we’d have won the war right there.”

On October 23, Halsey promised Vandegrift that he would send everything he had. The assurance came just in time. Vandegrift was going to need it.

The Battle of Henderson Field

Vandegrift’s men dug in behind their barbed wired perimeter. They knew the Japanese had beefed up their manpower and would soon attack. Unbeknownst to them, however, the Japanese could not supply those men.

Despite the continuous pounding, the “Cactus Air Force,” Guadalcanal’s pilots, had made adequate supply runs very difficult. Only a fraction of the needed food, ammunition, and medical supplies actually made it ashore to the Japanese troops. The Navy did its part too. Several sharp actions turned back desperately needed Japanese supply ships. Destroyers could deliver men but could not carry large quantities of supplies and equipment.

The underfed and often sick enemy soldiers hiked miles of tortuous jungle trails to reach the American perimeter. When they arrived, they continued their ruinous tactic of charging headlong into the American defenses screaming “Banzai!” Unfortunately for them, the Japanese Army considered fighting spirit more valuable than tactical training.

The night of October 24-25 was no different. Waves of Japanese soldiers crashed into the Americans, who answered with a rain of steel and lead. The Americans inflicted a seven-to-one casualty ratio on their attackers that night.

But at dawn, a Japanese soldier thought he saw green-white flares in the sky, the signal that Henderson Field had been taken. He quickly passed the information up the command chain. The Japanese admirals sent everything they had at Guadalcanal, trying to force the American fleet to a final battle. The result was the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands, in which the Americans lost the carrier Wasp, and two Japanese carriers were badly damaged.

The three-day Naval Battle of Guadalcanal followed in November and saw the Japanese Navy soundly defeated and sent reeling back toward Rabaul. Halsey had delivered on his promise.

Endgame on Guadalcanal

The Guadalcanal Campaign was enormous. Too enormous to cover in one article. I’ve chosen to focus primarily on the ground campaign, given the readership of this blog. Even so, I focused only on the actions of the Marines due to length restrictions. Once most of the Marines left, the US Army still had to kick the Japanese off the island. But the ground actions would not have been possible without the constant efforts of the Cactus Air Force and the Navy cruisers and destroyers that slugged it out in the darkness of Iron Bottom Sound. Equally important were the Seabees who braved bombs and shellfire to keep Henderson Field operational, and the massive logistical effort to keep troops, equipment, and supplies flowing to Guadalcanal, even if it was sometimes a trickle.

Guadalcanal was a campaign of attrition. It was exactly the kind of campaign the Japanese could not afford to fight. Beginning in December, US air and naval power took such a toll that Japanese supply runs rarely delivered more than ten to twenty percent of their cargo. Soldiers ate lizards, insects, and whatever edible plants they could find. Prowling American fighter planes and dive bombers constantly harassed the starving men.

Between August 7, 1942 and February 9, 1943, Japan lost approximately 14,700 soldiers killed or missing, with another 9,000 dead from disease or starvation. The Americans suffered 5,875 total casualties, with 1,592 killed in action. The ground campaign was a defensive victory, but it was no less decisive for it. Vandegrift played the hand he was dealt, and no doubt saved thousands of American lives by letting the enemy come to him. The Army campaign, as noted, was offensive in nature, finally forcing the Japanese out in February 1943.

Each side lost between 600 and 700 aircraft, but the Japanese came out far worse. Unlike the Americans, Japan did not rotate its aircrews for rest and recuperation. Plus, most of the air actions took place over or near Guadalcanal, meaning the Americans could often recover downed pilots while the Japanese could not.

The Japanese lost the cream of their pilot force in the Solomons Campaign, most of them over Guadalcanal. The American pilots gained valuable experience and passed it on as instructors and unit leaders. The Japanese lost their pilots’ experience forever. New pilots coming out of shortened training programs proved more and more vulnerable to the increasingly lethal American pilots in their new planes.

The Japanese lost thirty-eight ships and the Americans twenty-nine, including two carriers, during the fight for Guadalcanal. Iron Bottom Sound earned its name. Even today, the dozens of ships sunk off Guadalcanal affect the compasses of passing vessels.

But the US Navy learned as well. Despite the Japanese night-fighting superiority, the Pacific Fleet was ahead in radar development and by the end of the campaign, American ships could land their first salvo on enemy ships before they could fire.

The Japanese successfully evacuated 10,652 men from Guadalcanal in February 1943. They left 16,800 of their dead comrades behind, many unburied. Most of the skeletal soldiers who made it to the Japanese base at Rabaul had to be carried ashore. They could not speak and could barely eat or drink.

After the war, Japanese commanders said they only talked about two battles that might have turned the war their way: Midway and Guadalcanal. Midway evened the balance in the Pacific. Guadalcanal, by grinding down the Japanese army, navy, and air force, tipped it toward the Americans.

The limited Japanese training systems could never replace the quality of men they lost. American material superiority would not be felt until late 1943. But by the middle of that year, Japanese training was slipping, while American training ascended. Guadalcanal and the ensuing Solomons Campaign was not only “the graveyard of the Japanese Army,” it was the graveyard of the entire Japanese war effort.

Recommended Reading (In no particular order):

The Conquering Tide by Ian W. Toll

Neptune’s Inferno: the US Navy at Guadalcanal by James D. Hornfischer

Guadalcanal by Richard B. Frank

The Struggle for Guadalcanal, August 1942-February 1943 by Samuel Eliot Morison

Guadalcanal 1942: The Marines Strike Back by Joseph N. Mueller

Morning Star, Midnight Sun by Jeffrey R. Cox

Blazing Star, Setting Sun by Jeffrey R. Cox

Guadalcanal Diary by Richard Tregaskis

Helmet for My Pillow by Robert Leckie

The Cactus Air Force by Thomas G. Miller

Midnight in the Pacific by Joseph Wheelan