For most of firearms history, small arms were single-shot. That is, they had to be reloaded after each shot fired. But as long as there have been firearms, there have always been attempts to get more shots between reloads. The cap and ball, or percussion, revolving rifle was a successful design that was an ultimate dead-end. Although goofy and potentially dangerous by modern standards, the revolving rifle is a force multiplier worth an honorable mention.

What’s a Revolving Rifle?

To understand the revolving rifle, we have to start with what we mean when we refer to them. If we boil it down, revolving rifles are simply multi-shot revolvers with a rotating cylinder loaded with ammunition. The key difference is that the revolving rifle comes with a buttstock and a longer rifle-length barrel.

The concept of the revolving rifle existed in practice with the introduction of the matchlock musket as a means of having more ammunition capacity. The typical smoothbore musket or rifle had a single barrel and could only fire one shot at a time before reloading by dropping powder and ball down the muzzle. If reloading was so cumbersome, it made sense to have a way to have pre-loaded ammunition ready to go.

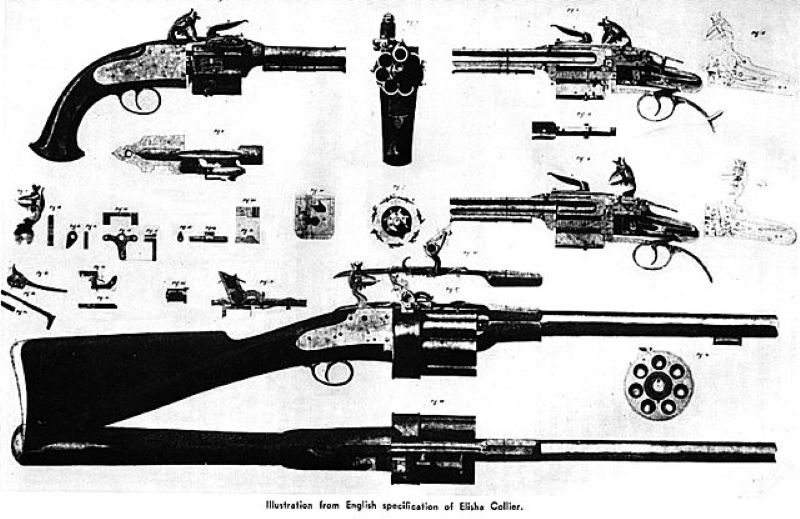

In the flintlock era, machine tool technology had advanced to the point where the revolving rifle could practically be made in any number. The Collier flintlock revolver of the 1810s featured a hand-rotated cylinder that held multiple rounds that indexed with a single barrel. It was also available as a revolving-cylinder long gun.

The Colt Ring Lever Rifle

Samuel Colt set up shop in Paterson, New Jersey in 1835. Through last-minute tool-ups and tedious outsourcing, Colt assembled a gun that some believed would be impossible to produce. That gun would become known as the Colt Paterson, the first practical revolver.

The percussion cap was a copper cup packed with impact-sensitive mercury fulminates that would explode when struck. The flame from the cap would flow through a hollow tube into the main charge directly. It was safer than exposed priming powder and far more waterproof. The Paterson’s cylinder had five tubes, or nipples, at the back of the cylinder. The front of the cylinder was open for loading powder and ball. Afterward, each nipple was capped. Hence the term, cap and ball.

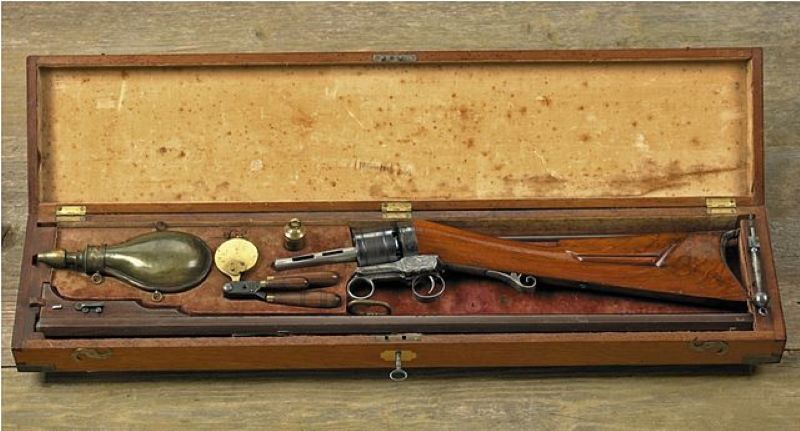

The Paterson was a ground-breaking handgun in its time and Colt understood that this repeating technology could be adapted to a rifle or shotgun. Between 1836 and 1842, Colt’s Patent Arms Company produced close to 1,500 revolving rifles modeled after the Paterson handgun. These are called the Colt Ring Lever rifles and they were made in calibers ranging from .34 and .44 with barrel lengths of either 28 or 32 inches. The rifles had an internal hammer that was cocked with a ring under the cylinder frame. An eight-shot cylinder came standard.

The Colt Paterson and Ring Lever rifles gained some favor in the new Republic of Texas, which had recently finished its war of Independence with Mexico and was desperate for arms. The US Army’s Second Dragoons also made an ad-hoc purchase and issue of the Colt Ring Lever for use in the Second Seminole War. However, sales were never brisk and the new gun was deemed too complicated for martial use. In 1842, the Patent Arms Company went bust.

Colt 1855 Sidehammer

The Mexican War revived interest in Colt’s revolvers and by 1855, Colt’s Manufacturing Company had factories on both sides of the Atlantic. Sam Colt’s revolvers in the form of the Colt Dragoon and Navy pistols were the sidearms of choice for the American military. The handgun arena was going the way of the revolver, but it did not take off in rifle form. The US Army had gone from a smoothbore flintlock in the form of the Model 1816 musket to a percussion cap rifled musket in the Model 1855. It was still a single-shot muzzleloading arrangement.

Around this time, the Army began to look at percussion breechloading rifles. Wanting to capitalize on the goodwill he had built up by supplying the Army with his proven revolvers, Colt took another stab at the revolving rifle. That rifle is the New Model 1855. But the rifle was more of the brainchild of his influential engineer Elisha Root. Root had designed a unique side-hammer revolver with a solid frame and cylinder pin.

The Colt 1855 was adopted by the US Army as its first repeating rifle that year, but it never became standard issue. In an act that would echo into the struggles of John Garand and Eugene Stoner, Army bureaucrats were distrustful of arming privates with a rifle that was mechanically complicated with more ammunition that could simply be wasted in a fight.

But in this case, there was more cause for alarm. A revolving rifle cannot safely be held the same way as an ordinary single shot. The outstretched arm that supports the barrel can be peppered with hot gas from the gap between the cylinder and the barrel. Worse, the percussion system still did not completely eliminate chain firing of all the chambers at once. Troops had to be instructed to brace both hands under the trigger guard, an unnatural shooting stance to commit to habit.

Period sources claimed that ill maintenance and gunpowder leaks from the front of the cylinder could cause all the chambers to fire at once, causing the shooter to lose his outstretched hand. Modern cap and ball shooters can generally nail down chain fires to either loose-fitting caps or undersized projectiles that would allow flame from one cylinder to touch over to another.

The 1855 would be the revolving rifle to see full-scale combat. The Confederacy captured the lion’s share of the Army’s guns as they had been allocated to southern arsenals before the succession. The Union Army ordered more 1855s, but kept the gun at arm’s length. Just shy of 5,000 rifles were delivered before the end of the war. The Army would once again rely chiefly on the rifled musket, but single-shot breechloaders like the Ballard and Sharps rifle as well as lever action repeaters like the 1860 Spencer were issued and fielded with great effect. At the start of the American Civil War, Samuel Colt, in his capacity as Colonel of the Connecticut militia, offered to raise an infantry regiment and equip them with 1855 rifles. His offer was declined.

Through September, Rosecrans’ sought a decisive engagement with Bragg, and his reckless pursuit over tough terrain was stopped by a Confederate ambush along Chickamagua Creek. In short order, the smaller Confederate forces had the larger Union force pinned on three sides and Rosecrans himself fled ahead of his troops back toward Chattanooga. The 21st Ohio Infantry Regiment, armed mainly with Colt’s .56 caliber revolving rifles, held off the Confederate assault, firing over 44,000 rounds of ammunition over the course of the six-hour engagement. Low on ammunition, the 21st retreated at nightfall. Cut off and unable to be resupplied, the remnants of the 21st surrendered the next day with empty rifles. Chickamagua was the last great Confederate victory of the war, but the 21st Ohio and their Colt rifles allowed the Army of the Cumberland to live to fight another day.

The Colt 1855 Sidehammer acquitted itself well in anecdotal engagements, but post-war the Army was happy to surplus the rifles at a loss. Colt also gave up on the rifle as production ceased in 1864.

The Revolving Rifle Today

For all of its potential issues when used in a conventional offhand shooting stance, the revolving rifle continues to have an appeal. Taurus is among a few companies to offer a revolving shotgun. Their 45/410 circuit Judge copies their best-selling Judge revolver and is faster to reload than a conventional pump action shotgun. Over the last few years, Heritage Manufacturing has been making their Rancher Revolving carbine in .22 rimfire. But if an old-school cap and ball revolving rifle is your taste, Uberti has long produced a copy of Remington’s 1858 rifle.

The cap and ball revolving rifle, for all of its drawbacks, was probably the most viable repeater before self-contained cartridges became a reality. It is an interesting link between the muzzleloader and the repeater that continues to have a niche appeal despite its short but prominent life.