Opinions on defending your life with a handgun chambered in the .380 ACP cartridge have been divided for decades. Today, the .380 is typically chambered for pocket pistols, and in that role, the round lies between larger duty-sized handguns and small-caliber pocket pistols. It is the largest caliber you can generally get in something that will fit in your pocket. But it is light for a larger handgun. Some say the .380, particularly with the latest ammunition, is adequate for self-defense, while others will state that it is inadequate.

The .380 ACP: What Is It?

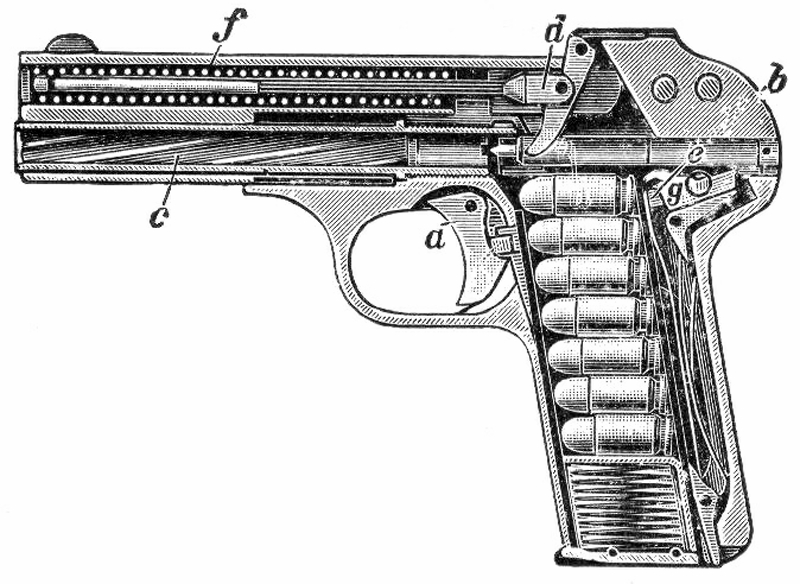

John Browning’s Model 1900, 1903, and 1905 handguns were the first viable slide-operated semi-automatic handguns as we know them today. They were also incredibly simple. Both featured a fixed barrel and a stiff recoil spring to keep the pistol locked when firing. When pressure fell to safe levels, the recoil of the round leaving the barrel drew the slide rearward to eject the empty case and pick up a new round from the magazine. It is what we would call a blowback-operated handgun.

These early handguns were chambered in .25 ACP and .32 ACP. But in those days, larger bores translated to more power impacting the target. Browning created the .380 ACP for the slightly larger Model 1908. It used a .355 inch or 9mm 95-grain jacketed bullet, which is more impressive than the preceding cartridges but small compared to larger service handguns of the time, like 7.63 Mauser, 9mm Luger, or .45 ACP.

The .380 has since become the biggest round you could chamber into a compact handgun. Despite the advances in firearms technology from polymer frames to hollow-point ammunition, the .380’s niche has held true. However, both advances have propelled the .380 to the forefront of the modern concealed carry movement. Polymer-framed pistols like the Kel-Tec P3AT and the Ruger LCP came online in the 2000s and offered more power in a package that was lighter than what could be had in other calibers, both large and small.

.380 Pocket and Compact Pistols: The Shootability Aspect

Although it is the biggest of the small caliber handgun rounds, the .380 ACP also has a reputation for being soft shooting. The .380 ACP delivers a 95-grain bullet at about 900 feet per second, while the 9mm Luger delivers a heavier 115-grain bullet about 200 feet per second faster. Based on these factory stats and the physical size of the round compared to the 9mm, some gun owners believe that the .380 is easier to shoot and will recommend the round to a new shooter. However, the .380 is typically chambered in handguns that are barely bigger than an iPhone. When touched off in such light-weight guns, recoil from the .380 can make it prohibitive to practice and shoot well. There is simply not enough weight to balance recoil forces and often not enough real estate to get a proper grip to maintain control.

Comparable Ballistics

GunMag Warehouse has a healthy assortment of .380 ACP ammunition, and I have had the privilege of testing just about all of them in ballistics gelatin. In those tests and beyond, the test platform I used was my trusty Ruger LCP. Unloaded, it weighs 10.2 ounces, carries six rounds in a standard magazine, and wears a 2.75-inch barrel. It is the ubiquitous .380 pocket pistol, and it approximates what most people carry if they carry a .380.

When I first started testing .380, I came to believe that the newest and greatest ammunition that rehabilitated the round in the current concealed carry market was flawed. Historically, carriers of the .380 relied on the old-school 95-grain FMJ load. It penetrates well, but it pokes .35 caliber holes. Modern defensive hollow-points are said to work out some of the deficiencies of the .380, but in my own testing, I found these rounds to be a decidedly mixed bag. When fired from a gun like my LCP, most ammunition failed to expand and did little more damage than FMJ. But there was plenty of penetration to stop a threat. On the other hand, some boutique makers who load lighter bullet weights of +P ammunition produced great expansion but at the cost of limited penetration.

The only round I found that strikes the right balance in my LCP is the Hornady Critical Defense 90-grain FTX. The polymer wedge in this bonded hollow point ensures proper expansion, but there is just enough velocity to get adequate penetration, whether through bare gelatin or gelatin backed by cloth.

Recently, I came into a Walther PD380. It is a compact handgun with a larger capacity than my LCP. It also wears a 3.75-inch barrel. I began to wonder if that extra inch of the barrel would make much of a difference in terms of velocity, hollow-point expansion, and penetration when compared to a pocket gun like my LCP.

Reading the Data

On the range, I stoked both handguns with different kinds of ammunition and shot five-round strings over my chronograph from a distance of ten feet. The results are as follows:

| Brand | Velocity (2.75-inch Barrel) | Velocity (3.75-inch Barrel) |

| PPU 92 grain FMJ | 892 | 968 |

| Hornady Critical Defense 90 grain FTX | 912 | 1018 |

| Federal Punch 85 grain HP | 939 | 1042 |

| Speer Gold Dot 90 grain HP | 959 | 1061 |

Although a difference of 100 feet per second might not seem like much if you are a rifle shooter, when we are dealing with low-velocity handgun cartridges, that difference could be the difference. Across the board, the PD380, with its 3.75-inch barrel, delivers. An extra 100 feet per second might make the difference, particularly with bonded hollow points like the Hornady XTP American Gunner.

I turned back to the Hornady Critical Defense load to test how material that extra velocity was. This load is about as good as one can get for a short-barreled .380 load because it gives good expansion and penetration. However, good is a subjective view. The best I could muster in previous tests was two out of three. But it is better than no expansion at all.

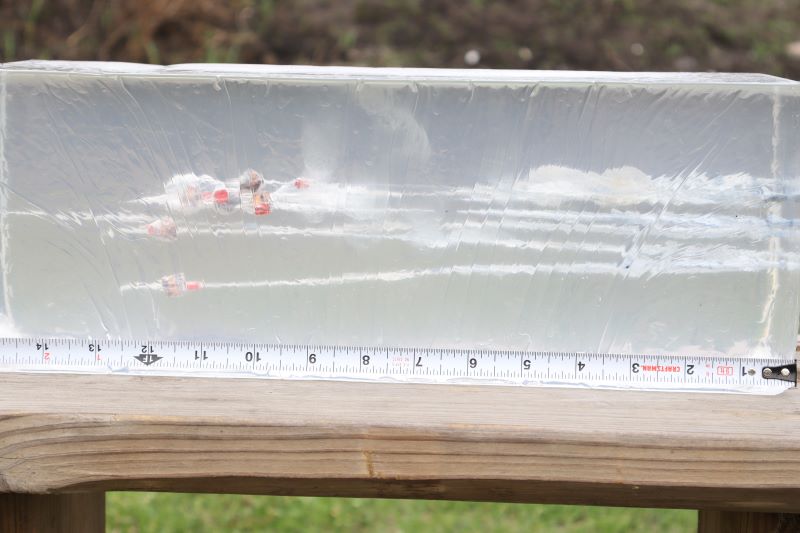

I loaded the Critical Defense ammunition into both handguns and fired seven rounds into a block of 10% Clear Ballistics gelatin blocks fronted by four layers of denim to simulate clothing. I fired three rounds from the Walther from 10 feet away and four rounds with the LCP.

Continued Testing

The first two rounds fired from the Walther stacked side by side, shedding their polymer tips and stopping after 10.5 inches of penetration. A third shot fired to the right stopped at 11 inches. The first two rounds from the LCP likewise lost their tips and expanded. One round traversed all 16 inches of gelatin, a sign of no expansion at all. A fourth round was fired and captured. These rounds stopped at 11.5 inches, 12 inches, and 12.25 inches, respectively.

The rounds fired from the Walther produced a larger stretch cavity, with stretching as wide as .75 of an inch between the two- and five-inch mark. At their higher velocity, the rounds expanded well—perhaps too well. This resulted in less penetration despite having more barrel to work with. All three rounds expanded to exactly .500 inch. The LCP’s shorter barrel produced just enough velocity to expand the projectiles but not so much that it radically expanded the rounds. The copper jackets and lead cores were peeled back in a more subdued manner, and the maximum expanded diameter of those rounds was .440 inches.

Conclusions

When we are told that .380 ACP ammunition has come a long way, the statement is not wrong. Likewise, when we are told that barrel length gives greater performance, it is not wrong. However, with the wrong combination of gun and ammunition, these statements are incorrect. Loads like the .380 ACP Hornady Critical Defense were created in the era of the short, barreled pocket gun and optimized for them. As we can see, the longer barrel of the PD380 gave us more velocity and more expansion of the projectiles, but with less penetration.

Overperformance does have its tradeoffs, and barrel length is particularly important with rounds like .380 ACP. As seen here, barrel length can work against you by taking an established and solid load and pushing it too far. On the other hand, more .380 rounds, even those made for shorter barrels, tend to fall short and can best be classed as mediocre. By going for a larger pistol with a longer barrel, greatness can be had from mediocrity.