Among whitetail deer cartridges, there are those that gain mass appeal quickly and then retain it to become standby rounds with their own peculiar advantages in the field. There are also niche rounds that are either outshined early on or too new for the market to catch on. The .223 Remington cartridge has ridden the rise of the AR-15 to make the jump from niche to mainstream.

Although some states prohibit the use of .22 caliber centerfire cartridges like the .223 for hunting whitetail deer, other states allow it. It’s very possible to take that stock AR-15 or one of the many bolt actions in .223 and go deer hunting. However, just because you can do something, does not mean you should. The banning of .22 caliber centerfire rounds in some states suggests it’s too underpowered for big game. I have certainly ran into my fair share of hunters who thought so. As a lifelong deer hunter and a man willing to play devil’s advocate, I had to test the .223 for myself.

I wanted to compare the velocity and subsequent velocity loss downrange. I also wanted to demonstrate performance on target. There is also the issue of bullet and firearm choice, since not all .223 ammo and firearms are created equal. To that end, I came up with a scenario of a typical AR carbine owner using a 55-grain soft-point. While the Hornady 55-grain soft-point and Smith & Wesson Sport II carbine I tested are not the best possible configuration for hunting deer, they represent what I consider a minimum working threshold.

Deer Camp Talk and the .223 Remington

The times certainly have changed for the .223. It was developed in 1957 for a new generation of intermediate-caliber autoloading rifles that were entering trials to replace the older, full-powered 7.62x51mm NATO M14 in American service. That experimental rifle eventually became the M16. But, even before the semi-auto AR-15 hit the market, Remington offered the .223 Remington as the next great varmint cartridge.

The .223 has its fans for varmint hunting. However, the .223 Remington doesn’t have the longer legs or flatter trajectory of the .220 Swift or .22-250. On the other hand, the .223 is appropriate for varmint work and its lower velocity relative to those other cartridges causes less barrel wear. Remington’s marketing efforts fostered the creation of a rainbow of hunting and target loads for the .223 that isn’t otherwise available with the similar 5.56 NATO. Rather, the .223 rode the rise of the AR-15, most of which chamber and fire both rounds.

Although I grew up hunting in a state where .22 centerfire is legal for deer, I always understood the .243 Winchester was the minimum threshold. The .243 was the stereotypical new hunter’s caliber because it had less recoil and tended to be chambered in shorter and lighter rifles compared to a typical bolt gun in .270 or .30-06. While flipping through an outdoor catalog, I noticed the .223. It was like the .243, but down a few fractions. I asked around and was told it was little better than a .22 rimfire for shooting at small stuff.

As time goes on, more black rifles are in the woods and quality familiar soft-point ammunition is more common on the shelf. While I haven’t hunted deer with .223, I’ve run into no shortage of men and women who harvested deer reliably and effectively with the round. Case closed, right? Well, not exactly. The anecdotes I’ve heard imply some limitations. The type of ammunition seldom comes up, although one person said they use only M193 55-grain FMJ. However, the range the shot was taken often came up. The furthest I’ve heard is 120 yards, but others prefaced they waited for particularly close shots “inside 100 yards.” There was an implied power limit making the .223 less capable. I’ve also heard the same said for the tried and true .30-30 cartridge. I began to wonder whether the .223 is truly marginal or if there’s more at play.

On Paper

On paper, the .223 has a lot going for it. Compared to other hunting rounds, the ammunition is inexpensive for practice and recoil is lighter than even the mild .243 Winchester or 6.5 Creedmoor. The .223 also has more match and hunting ammunition variety over the similar 5.56 NATO round. 40 to 50-grain varmint loads share the same shelf as heavier 75 to 80-grain match ammunition. Lighter rounds are marketed towards varmint hunting. These loadings use frangible and lightly constructed projectiles, which would result in inadequate penetration that make them dubious at best for deer.

55-grain bullets are the lowest weight for readily available bonded soft-point bullets. Rounds like these have more controlled expansion and hopefully give us game-getting penetration. The Hornady 55-grain soft-point has a bullet profile nearly identical to all other soft-points on the market. By far, it’s the most consistent round in its class on the market. As it happens, Hornady also supplies excellent ballistic calculations on their loadings. A look at their charts gives us an imperfect idea as to the .223’s capability.

Their soft-point load leaves a 24 inch test barrel at 3,220 feet per second (fps). At 100 yards, velocity drops down to 2,823 fps. At 200 yards, it’s down to 2,444 fps. With a 100 yard zero, the .223 only drops 2.9 inches. However, at 200 yards, velocity is down nearly 800 fps.

By comparison, Hornady’s 6.5 Creedmoor 129-grain soft-point, when shot from the same barrel length, has a starting velocity of 2,820 fps. At 200 yards, it’s down to 2,419 fps — a difference of 401 fps. The .223 bleeds velocity quickly and worsens with a shorter barrel. I fired the Hornady load over my Caldwell chronograph with my 16 inch barreled M&P Sport II and obtained a five-shot average muzzle velocity of 2,970 fps. I then shot through my chronograph at a distance of 100 yards and got an average of 2,669 fps. Out of curiosity, I also tested the excellent Barnes 55-grain hollow-point. At the muzzle, this load averaged 2,727 fps and at 100 yards, it hummed along at 2,366 fps. I now began to understand why .223 users pass on further shots. But all in all, how do these velocities and their loss affect the intended target?

Terminal Ballistics on Target

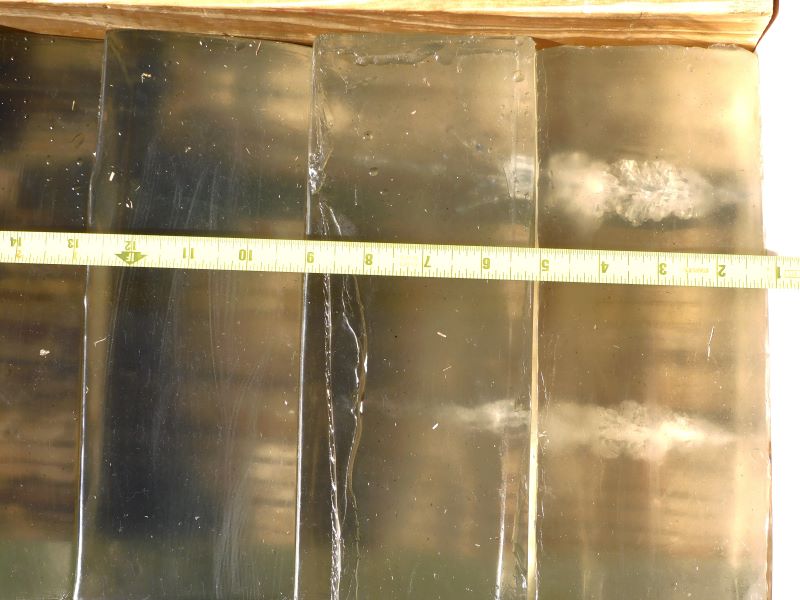

The best possible test of the .223 with any given load is to use it on game at a prescribed distance and record the results. I opted for a range contraption that I thought would be more fun and potentially more insightful. My “deer target” consists of two lengths of one inch thick pine board braced 16 inches apart by a standard 2×4. Within the bracket, I placed four blocks of Clear Ballistics 10% ordinance gelatin.

The pine boards loosely approximates the shoulder blades of a large whitetail deer, the most substantial bone you might have to shoot through on a broadside shot. It’s a wider chest cavity than I have seen on smaller Southern whitetail, but this size seems right at home on a well-fed Northern buck ready for winter. The insides of his “chest cavity” were less perfect. Ballistic gel is a good approximation for muscle tissue. Large bucks tend to have thick deposits of muscle and fat in the chest, as well as the heart. But, there are also two lungs made of softer stuff that we can’t really account for. For our purposes, I wanted to see how far each round could go in this controlled setting after dumping its energy to break through bone to get to the “vitals”.

I set my deer target on a platform 50 yards from the firing line and shot a Hornady soft-point on the left side of the bracket with the M&P Sport II. The force of the impact was enough to disassemble the target and spill it on the ground. I reassembled it, put my blocks back in order, and then hit the right side of the bracket with the Barnes 55-grain hollow-point load. Again, the target disassembled. After some careful washing, I put my blocks together to survey the damage.

The Hornady soft-point punched through the board, leaving a frayed .32-caliber hole on the back of the board. It dumped most of its energy into the board and first gelatin block. It created a 1.5 inch diameter stretch cavity that reached six inches into the target. To my surprise, the bullet fragmented and sent copper fragments out from the wound tract. From that point, the bullet’s path is nearly lost. The bullet was recovered just inside the fourth block, having broken through one inch of pine and 12.5 inches of gelatin.

I expected the Barnes load to break apart immediately, but its controlled penetration and expansion surprised me. It left a .22 caliber hole on both sides of the board. The Barnes also dumped its energy quickly into a smaller one inch cone terminating at the other round’s same depth. The round also penetrated the same.

The mangled Barnes 55-grain hollow-point’s copper jacket peeled back and almost separated completely. The bullet had an expanded diameter of .380 inches and held onto all of its weight during its travel. The Hornady’s jacket held together better and the bullet’s base was still visible. The lead core expanded to .428 inches in diameter with a final weight of 49 grains.

Analysis: Is the .223 good for deer?

I went into my little experiment both overestimating and underestimating the .223. I expected the Barnes hollow-point to break apart like a varmint round and not give much penetration after hitting “bone”. In addition, I expected the Hornady soft-point to sail through the target. Otherwise, I expected the backer to stop the bullet like a second shoulder blade. The Barnes round held up well and matched the Hornady soft-point hunting bullet. However, both rounds penetrated moderately overall. Heavier .223 rounds would be even better, provided you have a rifle that shoots them accurately. But, neither of them performed as dramatically in the penetration department as larger rounds. Larger, heavier rounds don’t have to contend with bone and velocity loss as much as smaller rounds like the .223 do.

After surveying the damage, I quickly visualized why .223 hunters use the .223, but also pass on shots at longer distances or without a perfect broadside. When paired with common ammo, my deer target is a worst-case scenario. While the target is larger than your average deer, the shot isn’t perfect broadside. Even so, it could be inferred the .223 Remington, in at least some standard loadings, will not penetrate well. The Hornady and Barnes loads penetrated more than enough for a double-lung shot. However, whether you get a straight through-and-through and a maximum blood trail is dicey. Furthermore, this is at 50 yards. What about 150? Even the .243 Winchester has a reputation for leaving no blood trail due to its relatively light weight and limited penetration. Depending on the size of deer in your locale and your expertise at closer broadside shots, the .223 will suffice.