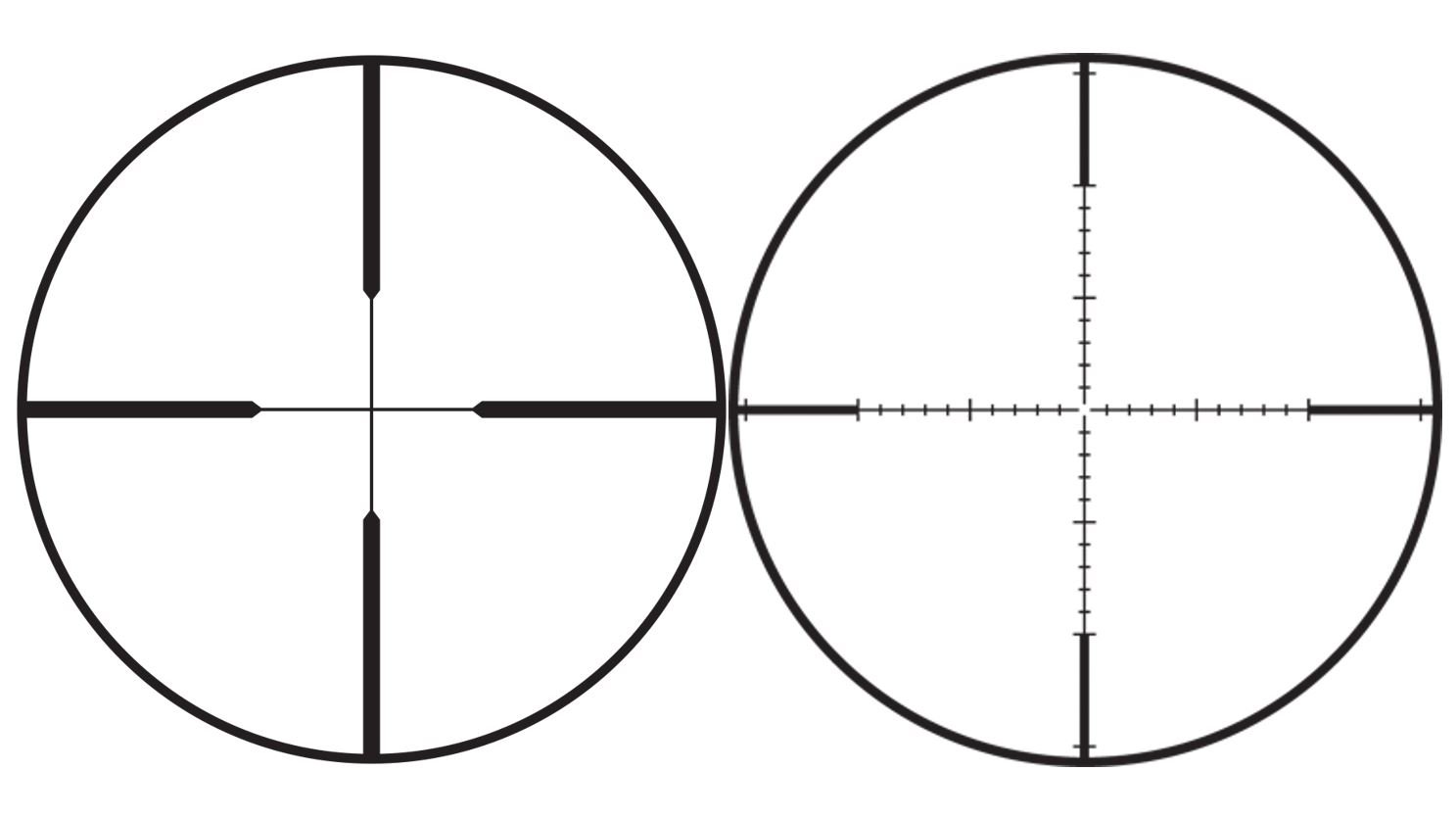

Reticles are the crosshairs or other markings that are visible when looking through the sight of a firearm or other optic device. A duplex reticle is the most common type of reticle seen in older hunting scopes. It consists of a crosshair with thicker lines at the edges that gradually get thinner toward the center. The idea behind this design is to provide a clear view of the target by minimizing the obstruction caused by the reticle. The thicker lines on the edges also aid in quick target acquisition.

A mil-dot reticle is a more complex type of reticle often used by military and law enforcement personnel and enthusiasts for long-range shooting. It consists of dots or hash marks spaced at specific distances along the crosshairs.

Growing concerns with duplex reticles were not having reference points for wind or elevation correction. Manufacturers began adding sub increments known as subtensions, into reticles that provided reference points to measure deviations in wind and elevation. As marksmanship became more precise, the need to break down subtensions more was important. Now, measurements are broken down into .2 mil increments. Modern technology provides relatively accurate measurements. As rapid engagements, lasers, and night vision techniques emerged, dialing became less of a process whereas using holdovers became the chosen technique for elevation. With holdovers becoming more prevalent, the tree-style reticles aid in the lower quadrants for having wind and elevation to identify shot corrections and to avoid disturbing the co-witness with lasers.

Understand and Apply

Using reticles for holdovers with elevation can be beneficial for several reasons. One major advantage is that it allows you to adjust for changes in elevation without having to dial in adjustments on your scope. This can be particularly useful when hunting or shooting in mountainous terrain, where elevation changes can be frequent and significant.

By using the correct holdover for the elevation and distance of your target, you can ensure that your shots land where you want them to, without having to make major adjustments to your rifle scope. Additionally, reticles with elevation holdovers can be easier and faster to use than adjusting your scope, especially in fast-paced shooting situations where you need to make quick adjustments. By relying on the reticle, you can make accurate shots quickly and efficiently, without sacrificing accuracy or precision.

Reticles come in diverse designs, but most have mils or minutes of angle (MOA). Mil-dots are the most popular and widely used, with every reticle manufacturer producing their specific mil-dot reticle. The mil-dot reticle consists of a series of dots spaced one mil apart. The dots can be used to measure how much of the target is covered by a specific number of dots.

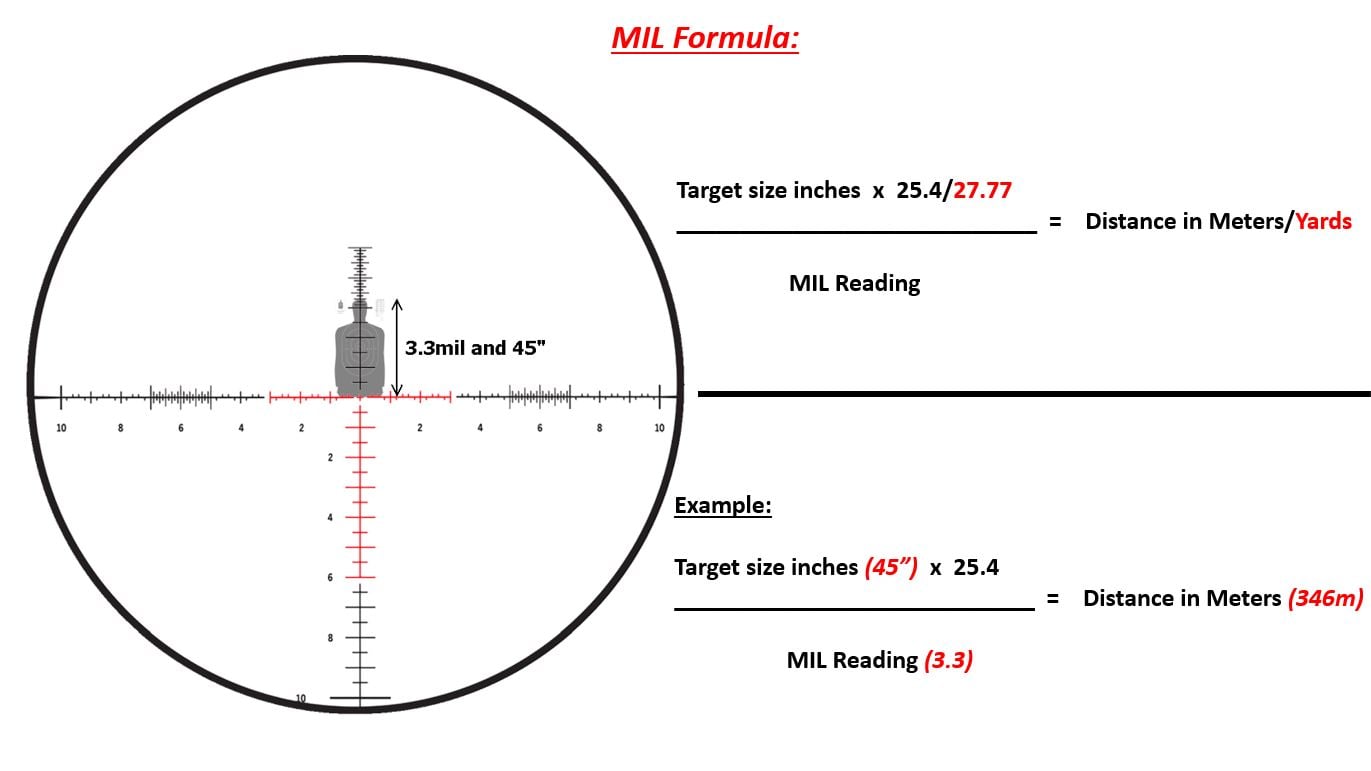

Once you have your reticle’s measurements down, estimating the range to your target is straightforward. Suppose you are using a mil-dot reticle, and a target fills up three dots within the reticle. If you know the size of the target, you can use that information to determine the range using the mil formula: the size of the target in inches multiplied by 27.77 divided by the number of mils equals the range in yards.

Practice Makes Permanent

While using a reticle to measure range takes some practice, it is an effective tool in a shooter’s arsenal, especially when shooting at long distances or in low light conditions when determining range visually is more challenging. Reticles are not only used for range finding but can also be useful in rapid engagement techniques and shot corrections. Both skills require you to understand your reticle and practice regularly. This will allow you to obtain greater accuracy and a more successful hunt or shooting experience. As with all shooting techniques, practice makes permanent.

Focal Planes

FFP Reticles

In an FFP (first focal plane) system, the reticle markings (whether that is a crosshair or other design) grow and shrink in size as you adjust the magnification. This means that the reticle increments remain proportional to the target at any magnification, allowing you to engage various targets accurately at different ranges. The FFP reticle provides more accurate range estimation across all magnifications and provides the same holdover points regardless of magnification. This makes it easier to quickly adjust the magnification for varying target engagements.

SFP Scopes

Unlike the FFP system, an SFP (second focal plane) reticle stays the same size no matter what magnification you set your scope to. SFP scopes are generally less expensive than FFP scopes, and provide excellent support at low magnification, allowing fast target acquisition on a moving target. Conversely, the reticle size is only accurate at specific magnifications, resulting in less effective range estimation. The holdover points in the reticle only work effectively at a specific point for your magnification. It is important to read the instruction manual for your SFP scope to know where the true magnification point is at. The reticle increments will change when not on true magnification, due to the fact that the reticle is not changing in size with the movement of magnification.

Both FFP and SFP reticles have their own advantages and disadvantages. If you are looking to engage targets at different ranges and want the same accuracy for shooting at all magnification ranges, an FFP scope is the perfect solution for you. By contrast, an SFP scope might be better if the scope’s intended purpose is for hunting at closer distances at lower magnification. As with all gear considerations, research is key.

MRAD vs. MOA Reticles

MRAD

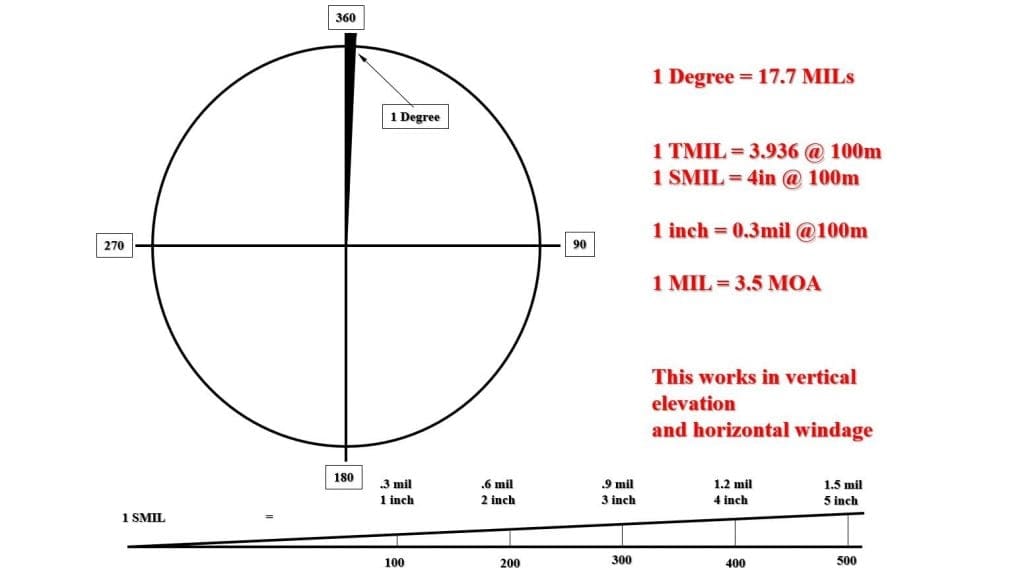

Milliradians, also known as Mils or MRAD, is a unit of measurement used in ballistics, navigation, and optics. Milliradians are commonly used by the military, law enforcement, and civilian shooters to measure angles, distances, and sizes of targets accurately. The mil measurement is divided into units known as tenths of a mil, which are commonly used in precision shooting. Many scopes today are manufactured in tenths, each click equals 0.1 mil requiring ten clicks to equate to one full mil. For example, if the data calls for 3.5 mil, the shooter will apply 35 clicks to adjust the reticle to the specific distance for the point of impact.

Range Finding

Range finding using milliradians is a technique commonly used by shooters and hunters to determine the distance between themselves and a target and is often used in conjunction with a mil-dot reticle on a scope to estimate range. To use milliradians for range finding, first, the size of the target must be known. This can be estimated using the mil-dot reticle on the scope. The reticle consists of small markings spaced according to the scope specifications, with larger markings spaced one mil apart. Once the size of the target is estimated, the number of mils it covers on the reticle can be implemented into the formula. Next, the known size of the target in height or width should be divided by the number of mils it covers on the scope. This will give a rough estimation of the distance between the shooter and the target in meters. Once the range of a target has been determined in mils, adjustments can be made to the scope to account for bullet drop. This is done by adjusting the elevation turret on the scope. Each click of adjustment on the turret represents a specific fraction of a mil, usually 1/10 or 0.1 mil (found imprinted on top of the scope turret).

In long-range shooting, mils are used to calculate the range to a target, which is crucial in determining the necessary adjustments to make for an accurate shot at the target distance. It is important to note that range finding using milliradians can be affected by a variety of factors such as atmospheric conditions, target angle, and scope magnification. Therefore, it is recommended to practice and refine this technique for distance accuracy.

The following formula for “mil ranging, or the mil relation formula” can be used to calculate distance.

Mil formula:

Target size (inches) x 25.4

______________________ = Distance in Meters

Mil reading

The stars in the sky

Mil measurements are also essential in navigation, especially in the marine or aerial environment, where precise measurements of angles or distances are paramount. For example, a ship’s navigator might use a sextant to take readings of the sun or stars in mils, which can be used to calculate their position on a nautical chart.

Mil measurements are predominantly used by snipers in today’s military. However, it was not uncommon for snipers to receive the older government-issued scopes that have mil reticles with minute-of-angle turrets prior to the transition to mil measurements. Conversions between the two were needed for measurements of targets and shot corrections which required extra steps prior to engagements. The ease of transitioning to one format has increased efficiency.

Overall, milliradians are a valuable tool for long-range shooters, allowing them to make precise measurements and adjustments for accurate shots. With proper understanding and use of mils, a shooter can effectively and consistently hit targets at extreme ranges, even under challenging conditions.

MOA (Minute of Angle)

Minutes of angle, or MOA for short, is a term used in the firearm industry that refers to a unit of measurement used for rifle scopes. Understanding what MOA is and how it relates to scopes can improve your accuracy and precision when shooting. MOA is used to measure the smallest adjustment that can be made to a rifle scope. This adjustment determines the amount of movement the crosshairs of the scope make when the adjustment knobs are turned.

Simply put, one MOA is equal to 1/60th of one degree or about 1.047″ (rounded down to 1 inch) at 100 yards.

For example, most scopes have a click value of ¼ MOA, which means that each click will adjust your bullet impact by ¼ of an inch at 100 yards. The relationship between MOA and rifle scopes is essential when it comes to making accurate shots. For instance, the ability to zero a scope is based on the adjustments that can be made. When sighting in a rifle, a shooter will use the MOA adjustment knobs to move the crosshairs of the scope so that the point of aim and point of impact align with each other on the target. Having MOA in your reticle can also be used to calculate adjustments when shooting at different distances. The ability to measure the deviation of the impact of the bullet with the target will aid in the required adjustments needed on the scope turret to have a point of aim point of impact alignment on the target. Understanding MOA can help you compensate for these variations.

Origins

Minutes of angle, commonly abbreviated as MOA, is used in a variety of fields such as astronomy, ballistics, and optics. The term MOA comes from the abbreviation of “minute of arc”, which traces its roots back to ancient Greece where astronomers first began measuring the position of celestial objects by their angles relative to the horizon. The Greeks divided the circle into 360 degrees, each degree comprising 60 arc minutes, and each arc minute comprising 60 arc seconds. This system of measurement became the standard for astronomers and navigators for centuries and the concept of minutes of arc as a unit of measurement slowly seeped into other fields, such as ballistics. The overall concept of minutes of angle as a unit of measurement has a long and rich history that has spread to other fields where it is used to measure accuracy and precision.

Putting in the work

To apply the concept, a shooter can adjust their optic’s horizontal and vertical turrets by a certain number of MOA to compensate for bullet drop or wind drift. For example, if a shooter has determined that their bullet impacts 20″ low at 500 yards, they can adjust their optic’s vertical turret by 4 MOA (1 MOA per 5″ of drop at 500 yards) to compensate for this deviation. MOA helps the shooter with making precise adjustments in the field. By making small and precise adjustments in MOA as needed, the shooter can achieve greater accuracy and make long-range shots with greater success. Understanding MOA and how it relates to rifle scopes can help any shooter become more accurate and efficient with their shots. Being able to make precise adjustments to your rifle scope with MOA will ensure that you are hitting your intended target.

The Choice is Yours

Ultimately, the choice of which reticle or focal plane to use depends on the shooting situation and personal preference. Mil-dot reticles are simpler and easier to use, making them ideal for beginners and general-purpose hunting applications. Tree-style reticles are more complicated but provide greater accuracy and versatility. This makes them ideal for more experienced shooters and those who need to account for long-range variables. The key to accuracy is understanding your equipment and plenty of practice.