Likely due to the influence of growing up during the Cold War, my thoughts automatically turn to worst-case scenarios. Knowing this, I try to balance this line of thinking with my knowledge of statistics and base rates. When preparing for emergencies I strongly endorse first preparing for the very short-term, then building out for longer-term emergencies. Following this advice, I conceptualize emergency preparation starting with immediate emergencies (first aid, fire prevention/mitigation, situational awareness/self-defense).

Once the needed skills and materials are acquired for dealing with immediate emergencies, each next level of preparedness can be conceptualized by the length of the emergency: short-term (up to a week), intermediate (a week to a month), long-term (a month to six months) and permanent (more than 6 months). I have developed this time-based categorization of levels of preparedness as well as what is

needed for each level in other articles here on The MagLife Blog, but for this article, I want to focus on long-term to permanent emergencies. Thus, we have some questions to ponder:

- What are the various events that could result in a permanent disruption of services (even full societal collapse)?

- How likely is each possibility, and approximately how would it play out if it happened?

All data presented here came from multiple sources — bi-partisan think tanks, U.S. government websites, conservative and liberal news sources, and global sources such as the U.N., WHO, and foreign media. As far as any numbers, probabilities, or rates presented, I made an effort to only present data that was agreed on across sources.

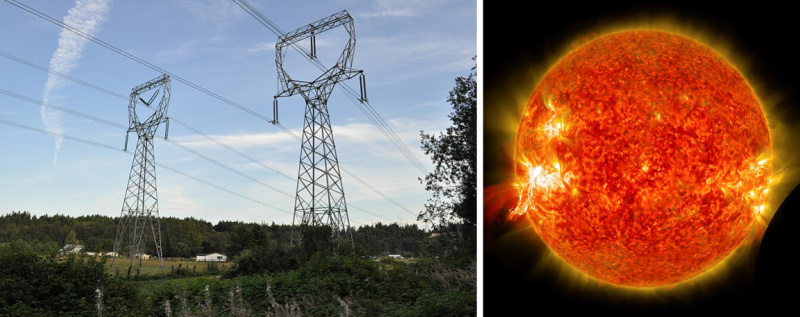

U.S. (or World) Power Grid

Although there are too many variables to easily quantify the risks, many experts agree that one of the greatest vulnerabilities in our modern world of power and data is our power grid. Simply put, the power grid is our physical infrastructure used to support the transfer, storage, and use of power. The power grid is often thought of in terms of just power but in the modern age, this also includes communications and data.

There are three main ways that our power grid could be compromised beyond localized events like extreme storms.

Aging Infrastructure

The first potential for compromise to our power grid is just aging infrastructure. Experts have been warning about the overall fragility of the U.S. power grid since the 1970s. Although such infrastructure issues usually result in isolated smaller instances, a domino effect of failures has been proposed as a possible outcome of not updating our grid. Additionally, the easily disrupted nature of the U.S. (and other countries) power grid makes the next two possibilities more likely.

Global Catastrophe

The second potential event that could compromise the power grid would be a natural worldwide event, such as a strong geomagnetic solar storm. The chance of a solar storm ending life on the Earth is very small as our sun has become relatively stable and will remain that way for billions of years. However, scientist’s best estimate is that we are hit with a severe geomagnetic storm about once every 100 years or so. Such a storm will not have much direct impact on life but might be devastating to our power and communication grids. The last major such storm was in 1859 and caused damage to the communications (telegraphs) of the time. By most metrics, we are somewhat overdue for such a worldwide event and most experts expect one to hit within the next 50 years.

Attack

The third possibility is an intentional attack. This could range from intentional EMP (atmospheric nuclear) detonations, physical attacks on crucial power nodes, or computer-based cyber disruptions. Terrorist attacks, if well-coordinated, could cause long-term damage, and overwhelm our ability to quickly repair our power infrastructure. A U.S. congressional study suggested attacks on as little as nine critical locations could all but cripple the entire U.S. power grid for months.

As more and more of our power grid becomes automated and interconnected by computerized operating systems, this attack could be carried out virtually, gaining the same impact. As power goes, so do other emergency and non-emergency services. Although there are too many factors for any experts to put an overall percentage to such an event happening, most agree it is more an issue of when than if. I would also be remiss here if I did not recommend “Lights Out” by Ted Koppel, which is an easy read for this complex topic.

Pandemic

We all have a better idea of what the fear of a global pandemic and the potential results of public and political reactions are after living through 2020-2021. Some might argue that there are ongoing ripple effects continuing well into 2023. Looking at the data now in 2023, most estimates placed the COVID-19 virus at an estimated 2-3% mortality rate (worldwide and including mild, early, and later cases).

The estimated maximum R0 of COVID-19 was 2.5 (meaning one infected person was likely to infect slightly more than 2 others). By comparison, the mortality rate of the common flu is closer to 3.5% (this figure is likely driven by only more extreme cases as most mild cases are unreported) but with an R0 closer to 1.5. The most recent, more virulent pandemic was in 1918 with the Spanish flu (mortality at 7% and an R0 of 3). Viruses such as COVID-19 and the Spanish Flu are of special concern as they are easily contracted through airborne transmission.

Experts estimate the world’s chances of seeing such a ‘superbug’ are approximately 1-3% per year. Although this may seem low risk, it does mean such an event is 55% likely over the next 40 years. Such events, depending on political and public reaction, can have wide-ranging impacts on our infrastructure, medical services, and economy. Similar events in general are likely to only cause short or intermediate disruptions. However, if a new virus similar to smallpox suddenly appeared, (mortality rate of 30% with an R0 of 6 or more), with no immediately known treatment or vaccine, the impact on travel, commerce, medical services, and economies would be overwhelmed, likely resulting in a long-term disruption.

Experts have not placed a probability on such an event, but similar contagions have been seen in history — during times when global travel was not an option. Another excellent book recommendation is David Quammen’s “Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic” which was published pre-COVID. The book highlights just how intertwined our ecosystem really is.

Economic Collapse

Although global economic collapse is thought of as a consequence of other events such as power grid collapse or pandemic, it could also become a cause. In hindsight, the relatively minor pandemic of COVID-19 and the responses to it directly resulted in a 6% drop in global growth and a 3% drop in the total world economy in 2020 (though there was a sharp increase in both in 2021). Though few experts expect the global economy to collapse, most are forecasting a global recession is likely in the next 10 years.

Like many potential causes of a long or permanent disruption, the question becomes how many events (banking crash, aviation industry woes, supply chains, etc.) would it take to spiral a recession into a full collapse? There have been multiple examples of localized economies collapsing in recent history such as Hungary in 1945-1946, Yugoslavia in 1992-1994, Zimbabwe in 2007-2008, and Venezuela in 2017-2018. One needs only look at the impact in such countries even with outside assistance and an overall stable world economy to deduce what could happen if such an economic event became a worldwide phenomenon.

Global War

Although overall there have been fewer wars and war-related deaths since the mid-1980s, these numbers have been on the rise in the last decade — most being civil conflicts with or without foreign interventions. Although we live in peaceful times compared to the period starting with World War II (1939-1945) and ending with the Cold War (1991), conflicts are currently on the rise as well as driving larger shifts in population and extremist actions.

Examining nuclear stockpiles, the following countries are known to have nuclear weapons:

- Russia (6000)

- United States (5,400)

- China (350)

- France (300)

- India (150)

- Pakistan (150)

- United Kingdom (120)

- North Korea (30)

- Israel (100) *though not confirmed or denied

Of these nine nuclear powers, the U.S., Russia, China, the U.K., and France all have delivery systems capable of deploying these weapons worldwide either through intercontinental ballistic missiles, or submarine-launched missiles. Additionally, the following countries host nuclear weapons: Italy, Turkey, Belgium, Germany, Netherlands, and Belarus.

The only country to leave the nuclear club is South Africa, which ended its nuclear weapons program in 1989. There are six unaccounted-for nuclear weapons (most lost deep at sea) and over 2.5 tons of uranium missing after the collapse of Libya alone. The doomsday clock (a hypothetical measurement of the risk of global nuclear war) is currently the closest it has ever been based on the uncertainty of certain nuclear powers. As of 2023, we are less than two minutes to midnight (nuclear war) even beating out the time settings at the height of the Cold War. Though no longer at the center of the public consciousness, global devastating war is still a real possibility.

ELE: Extinction Level Event

An extinction-level event usually refers to something out of human control, or no longer under human control, that results in a significant extinction of the majority of animal and plant life. Such natural events occur about every 100 million years and generally result in ~70% of animal and plant life becoming extinctic. These events are generally believed to be caused by runaway rapid climate shifts caused by multiple possibilities including over-production of atmospheric gases by natural processes, volcanic action, or asteroid impacts. The big five such events include:

- Ordovician-Silurian extinction — ice age followed by global warming — 442 million years ago.

- Devonian extinction — several environmental stresses — 374 million years ago.

- The Great Dying — massive volcanic eruptions and runaway warming — 250 million years ago.

- Triassic-Jurassic — several environmental stresses — extinction 201 million years ago.

- Cretaceous extinction — asteroid — 65.5 million years ago.

If the average holds, we are not due for another 34.5 million years. If we go by the smallest gap which was only 49 million years ago, we are overdue.

Zombie/Machine Apocalypse

The final category is a catch-all for human-caused events that have an unexpected or greatly accelerated effect, compared to expectation. In this way, global war is not included in this final category. Climate change has definitely been a factor in previous extinction-level events. When looked at objectively, the current additions humans are making to the total carbon released in the atmosphere is relatively large at 9.5 million metric tons a year compared to natural wildfires at 1.75 million metric tons a year. Yet, it is small compared to the volcanic activity of 5.8 million metric tons from a single active volcano and 60 million metric tons from 30 relatively inactive but venting volcanos.

Such data is often used to ‘debunk’ human impact on the atmosphere, but we are essentially adding the equivalent of over one fully active volcano to the equation per year. Those calling for action often exaggerate, but no one is completely sure what it takes to result in runaway climate change. We do know it has resulted in several extinction-level events in the past. Though Hollywood ‘zombies’ are not likely, some form of contagious bioweapon designed to ravage civilian populations is unfortunately no longer just science fiction.

Additionally, as we become more and more dependent on computers, data, and interconnected automated systems, movies that seemed farfetched such as “Terminator” are starting to become a credible concern.

I think there are two interesting points to make here.

- One, I think it’s important to recognize that our reactions to today’s level of automation are likely similar to what it was like during the Industrial Revolution (1760-1914). During that time, machines started to amplify the work of humans, allowing more work to be done in a shorter time with less effort. There was a lot of public fear when those innovations arose, similar to how there is fear (often legitimate) today about machines taking human jobs. I suspect most of our automation today will continue to amplify human abilities. Although this process will change the nature of work, I don’t think it will replace humans.

- Two, I think for the first time there’s also the very real possibility that, left unsupervised, our machines may start to learn and change without our direct intervention, and this possibility needs to be acknowledged. Machines learning and growing unaided by our direct intervention is very different from having a sewing machine simply amplifying the amount of sewing that can be done in a certain period. This difference is why many experts and critical thinkers are concerned about the dangers of rampant unsupervised AI.

Conclusion

The overall picture is that events that would result in a permanent disruption (collapse) of our current services are very unlikely, but also unknowable and greater than zero. In the face of such an event, one has to ask will there be a viable biosphere with arable land and breathable air after such an event? Even if there is, would you want to live through such an event?

However, there is a lot of ‘breathing room’ between total destruction and a permanent significant change in available services. Thus, make sure you are preparing for more likely events first. Immediate to long-term disruptions should be planned for before thinking about preparing for the END. That said, the END has many possible causes and does present a small but credible threat to prepare for, once shorter disruptions have been planned for.

Note: Special thanks to Meghan R. Lowery for her contributions to the content and context of this article.