If you hunt North American game, chances are you have an opinion on the 30-30 Winchester cartridge. Even if you don’t hunt, you still might have a take. From cowboy games to reindeer games, the 30-30 has been there and done that since 1895 and it carries on, having outlived many of its contemporaries.

Despite the round’s success, for every person who likes it, there is another that can’t be bothered with it. Why is that? Follow along as we explore the history, ballistics, and some of my own personal anecdotes to uncloud the mystery of the 30-30 Winchester—America’s first modern hunting cartridge.

And Then There Was No Smoke

In 1884, Paul Vielle created Poudre B, a gunpowder reported to emit no noise and no smoke. It became a French state secret and their army haphazardly adopted a rifle using this new propellant. As it turned out, the new rifle was still noisy, but there was no smoke. The Mle 1886 Lebel was not a groundbreaking design, but its 8x50mm Lebel cartridge was. In an era of exposed lead projectiles and white clouds of black powder, the Lebel round used jacketed bullets hurled twice as fast as anything that came. There was no smoke to obscure aim, give away the shooter’s position, or foul up the action with residue. The smaller 8mm cartridge had a flatter trajectory and equal hitting power to the contemporary 11mm and 45 caliber rifle rounds of the day.

The invention of smokeless powder opened up a deadly game of ‘keeping up with the Jones’ among the world’s Great Powers, but it also created new opportunities for those who lived day-in-and-day-out by the rifle.

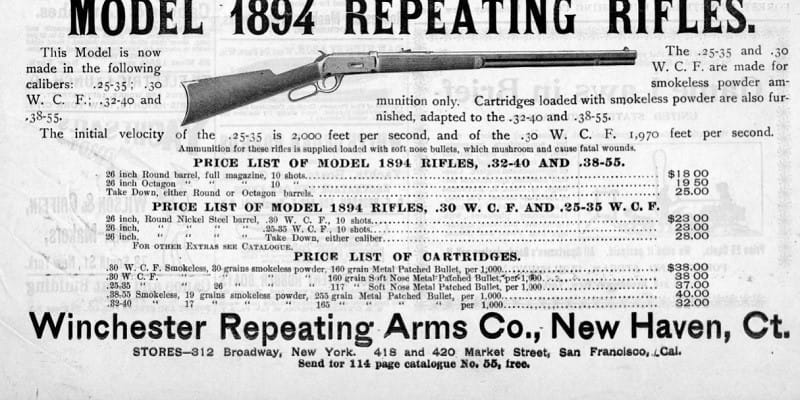

When Winchester debuted the 30 Winchester Center Fire paired with their Model 94 rifle in 1895, American rifle shooters were using a smattering of different black powder rounds. The 44-40 Winchester was the most popular. Winchester and Marlin, among others, sold countless lever action and pump action rifles, while the round found favor in handguns like the Colt Single Action and the S&W Double Action Frontier. Ballistically, it was a glorified pistol round. For shooting larger game and distance shooting, the 38-55 and 45-70 rifle cartridges were popular.

The 30 WCF was developed by taking the case of the 38-55 and necking it down to accept a .308-inch diameter flat-point jacketed bullet. Although never a black powder cartridge, the 30 WCF was described by Recreation magazine in 1896 as the 30-30—denoting a 30 caliber bullet backed by 30 grains of smokeless powder. In that edition, the new round was tested against other existing cartridges like the 32-40, 45-70, and 50-140. The new round launched a 160-grain bullet at over 2000 feet per second with as much muzzle energy as the 45-70 405-grain load. It had a flatter point-blank range, less recoil, and no smoke.

The Rise and Fall of the 30-30

To say that the 30-30 Winchester was popular is an understatement. From 1895 to the present, over 7.5 million Winchester 94s have been made, with the lion’s share of them in 30-30. The Marlin Firearms Company snatched the round for their Model 1893 rifle and their subsequent 336 series of lever actions, likewise produced in their millions.

Although the 30-30 is largely confined to lever action rifles, gunmakers have used the cartridge creatively. It was offered in some large-framed handguns like the TC Encore and the Magnum Research BFR. Henry Repeating Arms is but the latest iteration of a 30-30 single-shot rifle and in the past, the Savage 340 bolt action in that chambering was a common item.

Although the 30-30 has proven useful on game as large as elk and bear, the round’s reputation was forged as a whitetail deer cartridge—especially with shots taken within one hundred yards. The 30-30 was the first deer rifle for many Americans. Given the number of 30-30 lever guns out there, that adds up to a lot of venison.

Fast forward to the late 1990s. My age was still in single digits and my first deer rifle was a late production Winchester 94 in 30-30. At that time, my entire extended family hunted and with every passing season I heard more words of caution than optimism over my use of a 30-30. I grew up with the 30-30 being a short-ranged, low-powered round suitable for beginning hunters. It was only much later did I find out that the 30-30s vaunted reputation. As it turned out, I was not the only one led to believe how lousy the 30-30 is. That caused me to ask the following: Is the 30-30 really a lousy cartridge and why did it get that reputation? It ultimately boils down to lever action rifles as a platform and the terminal ballistics of the cartridge taken out of context. The decline of the 30-30 begins with the downfall of the lever action.

The Fall of the Lever Action

Lever action rifles have many advantages. Their tubular magazine can hold a fair number of cartridges and all it takes is a wrist flick to work the action. It is a fast-shooting platform that is lighter and thinner than many competing bolt action and semi-automatic rifles on the market. But the lever gun has seen a fall from grace in terms of technical innovation and manufacturing.

The lever gun is a fast-shooting repeater but it was never known to chamber particularly powerful rounds. Even in the 19th century, single-shot rifles like the Sharps and Remington Rolling Block excelled in the arena of long-range shooting. Fast forward to today and bolt action repeaters came in where the single-shot left off. Although powerful for a rifle round in its time, the 30-30 would be eclipsed by other .30 caliber rounds that could be thrown faster and achieve a flatter point-blank range.

The 30-30 was also cursed with a flat-nosed bullet and a prominent rimmed case head. The flat nose was, until recently, essential to a round functioning safely in the tubular magazine of a lever action rifle. Flat-nosed bullets stacked primer to bullet tip had less of a chance of detonating in the magazine.

The rimmed case was essential for extraction in a lever gun and it caused no issues in a tubular magazine. But building a box-magazine-fed rifle around the 30-30 is tricky. The rims have to be stacked properly in order to feed and the magazines would have to be curved to accommodate more than a few rounds of ammunition. But few have bothered to try with the 30-30 because you can simply use a more modern rimless round that came loaded with factory spitzer-pointed ammunition that had a flatter trajectory to start with.

By the time of the Great War, most militaries had switched to spitzer rounds and sportsmen started to follow suit with the development of newer, faster, and more efficient rounds. In the years after the Second World War, surplus Springfields and war-prize Mauser and Enfield rifles flooded a hunting market that started to skew toward bolt action rifles.

While bolt action rifles grew in popularity and became cheaper and more available, lever action rifles produced by the likes of Winchester and Marlin became increasingly expensive to make and there were comparatively few innovations to answer the competition. The cost of labor became a sore spot for Winchester in the 1960s and shortcuts were taken. In 1994, the Olin Winchester plant shut down, ending American production of Winchester lever actions entirely.

In the gap, Henry Repeating Arms began producing lever guns. Marlin continued producing their Model 336 but rising labor costs and falling demand took their toll, especially after the Remington Arms Company purchased the company in 2007. By this point in history, the Clinton Assault Weapons Ban had ended and AR-style semi-automatic rifles in competitive calibers were making inroads against the lever gun—and the bolt guns as well.

In 2020, Remington went under and took Marlin with it. Since 2021, Ruger owns the Marlin company and has brought back a few of their designs. Although the lever gun continues to have some appeal, it is fair to say their market share has been in decline for decades. But along the way, as we have alluded to, the 30-30 round itself was heavily dated not long after its introduction.

The 30-30: From High to Low Power

There are compelling reasons to want a bolt action for hunting purposes over a lever action. Better accuracy and greater power are usually the reasons I hear. Mechanically speaking, most modern bolt action rifles like the Remington 700 and Savage Model 10 use box magazines that are blind to whether you use spitzer or flat-nosed projectiles. As before mentioned, the former excels at cutting through the air. It loses velocity at a lower rate and has a flatter point-blank range over a flat-nosed bullet. One could think of it along the lines of a torpedo versus a flat-bottomed skiff moving through water.

The bolt action also excels at handling cartridges that are too long for a practical throw of a lever. Most 30-30 loads have an overall length of 2.55 inches. A comparatively old bolt gun round like the 30-06 has an overall length of 3.34 inches. That extra length can be translated into more powder and greater velocity. A good 30-06 load will remain supersonic at 1000 yards, while the 30-30 will hang at that half that distance. Between 150 grain loads in each cartridge, muzzle velocity alone should be a dead giveaway. Most 30-30 loads like Remington Core-Lokt and Winchester Super X can be fired out of a twenty-inch rifle at 2200 feet per second at best. A comparable 30-06 load can get out near 2900.

Numerous wildcatters, gun writers, and manufacturers have developed new ways to skin this cat and there are quite a few bolt action (and semi-auto) rifle rounds that compare favorably to the 30-30. Old favorites like the 243 Winchester are out ahead, while newer, but capable rounds like the 300 Blackout are not far behind. Time since 1895 has indeed marched on. But in the context of its time, the 30-30 bested some of the known bison cartridges of its day. Indeed, the proponents of the 30-30 believe pushing a 30 caliber round faster is not necessary for most purposes.

In the Western prairie, the 30-06’s extra velocity is an asset, but it isn’t necessary for the thickets of the South where shots are often fast and close. The lower velocity of the 30-30 is also more friendly on the shoulder, allowing some to connect with a 30-30 instead of bearing a flinching miss with a bigger round.

Some hunters opine that the 30-30’s lack of velocity produces less of a blood trail over faster rounds, while others believe that the round’s traditional flat-nose produces more bleeding over a typical spitzer. In my own experience, neck shots with flat-point loads tend to drop whitetail on the spot. But I have seen similar results using Hornady’s LeverEvolution 30-30 Win. 160-grain FTX load. Take all of that for what you will.

What Range Is Short Range?

If we go by the velocities listed on boxes, we get the impression that the 30-30 is underpowered. It has the same muzzle velocity and energy that other rounds will have at three hundred yards. That, along with the usual flat-nosed profile of bullets loaded for the 30-30 have given it the reputation as a short-ranged cartridge. But at what range is short range?

When I was a kid, I went into the stand many a time with a Winchester 94. Mine wore a Bushnell 3-9×40 rifle scope. But I had to remember the cardinal advice I was given. If a whitetail walked beyond 100 yards, don’t take the shot. Even with a solid hit, the animal would wander off and eventually expire where I could not get to them. The 30-30 wasn’t high velocity and it had the trajectory of a thrown rock. But after years of shooting the 30-30 at game and on paper, I found all of that to be untrue.

With most 150-grain 30-30 loads I have tested, there is no discernable drop at 100 yards. At distances of two hundred yards, those pills drop between 4-6 inches. At three hundred yards, my groups dropped precipitously to thirty-two inches from the point of aim. My results with heavier 170-grain loads were worse.

I also tested the Hornady LeverEvolution 160-grain FTX load over the years. This round is spitzer-like and uses a soft polymer tip to allow the user to safely load the tubular magazine of the lever gun. Hornady states that the LeverEvolution round drops 12.1 inches at 300 yards. This is a result I concur with and one not dissimilar from other, more modern 30-caliber rounds. But even with the old-school soft point loads available, the 30-30 isn’t bad. But as I shopped, bought, outfitted, and shot a number of these rifles over the years, I found another reason the 30-30 gained a reputation as a short-ranged cartridge—the iron sights.

In 1895, there were few practical riflescopes around and most sportsmen used iron sights. The 94 Winchester debuted with a semi-buckhorn rear sight and a front blade—a setup that works well for close-range snap shooting, but these sights can appear big as the target gets smaller with distance.

After the Second World War, a popular modification for lever action rifles was the addition of Williams and Lyman tang-mounted rear aperture sight to give the user a finer sight picture. But by in large, most 30-30 rifles are, and still, come with the same notch and blade arrangement as in 1895. I did not immediately notice this as my first rifle was a late production 94 that came with a scope mount and used an angular brass ejector that kept brass from hitting the scope.

As it turns out, before 1964, all Winchester rifles I found ejected empty brass straight up. That kept scope mounting out of reach for most. The Marlin 336 and Henry rifles have a solid receiver and a side ejection port, allowing for quick and easy mounting of a scope. But even among those rifles, I was surprised to see shooters on the range running iron sights alone. When I asked one shooter if he preferred iron sights on his 336, he responded along the lines of, “A scope would be nice but you can’t get very far with a 30-30.” Thus, the 30-30’s reputation is partly based on the march of technology and the way rifles chambered for it came set up in the first place.

The Bottom Line

The 30-30 Winchester is the bumblebee of hunting rounds. The bumblebee, with its huge body and tiny wings, should not be able to fly—yet it does. The 30-30 should not perform as well as it does and it should not have stuck around for as long as it has.

While there are some compelling reasons to pass on the round, there are still plenty of reasons to opt for it. The rifles are quick-shooting, easy on the shoulder, naturally ambidextrous, and can be found just about everywhere. 30-30 ammunition is far from obscure to find and can often be found at a price point lower than other centerfire rifle rounds like 270 Winchester and 30-06. Although less powerful than those more modern rounds, it bears remembering that the 30-30 was the first modern rifle round available to the American sportsman and is still worth a look today.