If you go to your local sporting goods store and search out the ammunition section, the box will tell you most of what you need to know including the brand and bullet type. It will also tell you how much the bullet in the cartridge case weighs in grains. Given that bullets of the same caliber or cartridge do the same thing to a target, more or less, does the number of grains have an impact? The short answer is “yes.”

Whether you are new to shooting firearms and you run factory ammunition or are looking into getting into reloading your own rounds, knowing the grain weight of your projectile is a small but material part of shooting. Here is a breakdown of bullet weight and why it matters.

What is a Grain?

A grain is the smallest unit of the traditional English weight system. It was originally used as an approximate measurement for crop yields of real grains like wheat and barley. The grain we use today when we talk about firearms and ammunition was derived from the later avoirdupois pound; the 16-ounce pound we know today.

It takes 7,000 grains to make one pound and one grain is 1/7000th of a pound. The more the grains, the heavier the projectile.

Single Rounds and Different Grain Weights

With an increase in caliber, there is generally a gross increase in the grain weight of the bullet a gun will fire. But there are also different bullet weights within the same caliber.

When producing ammunition in mass quantities, manufacturers generally load a given cartridge with the same charge of powder regardless of bullet weight. Adding and subtracting grain weight can provide the shooter with different levels of performance without having to go to a larger or smaller caliber.

For example, most 9mm Luger rounds have a bullet weight between 115 and 124 grains, but 147-grain rounds are available. This 147-grain bullet load is meant to be a lower-velocity round that does not have a sonic crack when using a suppressor. The heavier bullet takes up more room in the cartridge case and creates more backpressure when the cartridge is fired, allowing the bullet to leave the muzzle at a subsonic velocity while still producing enough pressure to cycle the slide.

Traditionally, .38 Special cartridges were loaded with 158-grain bullets, but over time manufacturers began loading 110-125-grain projectiles to get more velocity and bullet expansion out of short-barreled revolvers.

Rifle Ammunition

When it comes to rifle rounds, the performance dynamic between light and heavy rounds is straightforward. In a given caliber, heavier bullets are generally longer. The length of a bullet is broadly called a ballistic coefficient. Bullets with higher ballistic coefficients tend to buck the wind and have less drop compared to those with lower coefficients. Depending on the bullet design, bullets with a higher BC can deliver more penetration on the target as well.

In the case of the .30-06, a 220-grain bullet’s mass is slow-going but with more than enough momentum to bring down large game like brown bears and elk. The same cartridge using a 110-grain bullet over the same powder charge will leave the rifle faster and with less felt recoil. The lighter bullet is fast to boot and fast to lose its energy in a target compared to the heavier round. This is not desirable for bigger game, but for light-skinned varmints or as a light deer load for new shooters, it can do the trick.

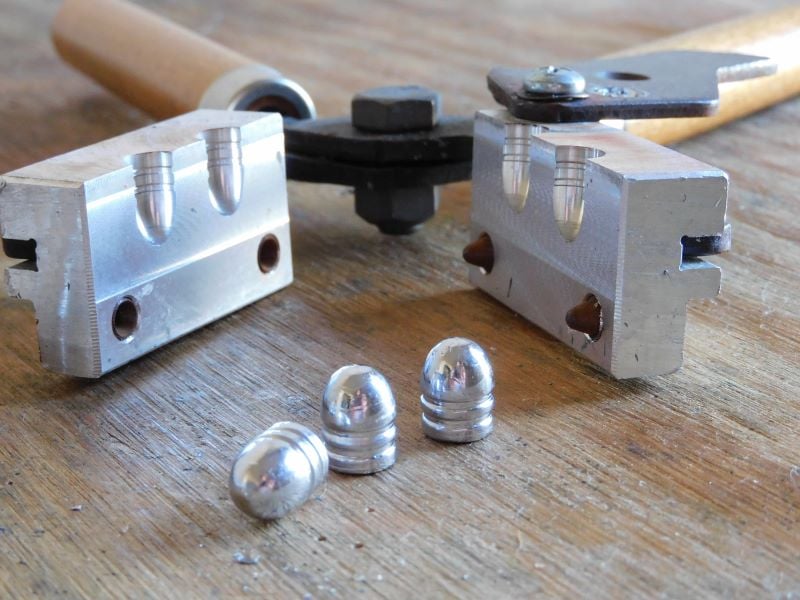

Translating Data for Reloading

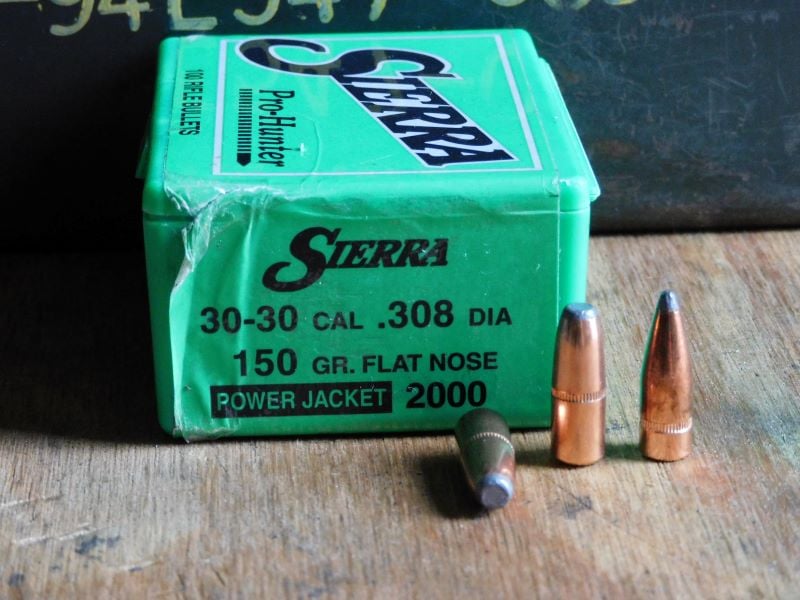

In the reloading world, projectiles are normally sold by caliber and weight, not by a specific cartridge designation. You won’t see .30-30, .308, or .30-06 bullets. You will see .30 caliber or .308 inch. With rounds like .380 ACP and 9mm, boxes of ammunition are usually marked .355 inch. So, the difference in bullet weight also comes down to the types of projectiles used in certain cartridges. Lighter .355-inch 90-grain bullets can be loaded in 9mm cartridges but are traditionally loaded in .380 rounds. Blunt-nosed 150-grain bullets can get a lot of use in a .308 or 30-06, but they are traditionally loaded in .30-30 ammo.

Reloading Considerations

If you are new to reloading your own ammunition and understand the why behind different bullet weights, you may have questions about whether you should treat reloading different bullet weights differently in some way. Can you do the same repetitive process of loading without changing anything? Can you use the same amount of powder?

Reloaders will generally fit cartridges and seated bullets into a maximum overall length that allows the ammunition to cycle in a firearm. Longer, heavier bullets will need to be seated deeper to achieve the same overall length. The bullet seating die in the press will need to be backed off for heavier bullets and torqued further for lighter ones.

If each cartridge is kept to the same overall length, the one with the heavier bullet will generally have more lead occupying the inside of the case, reducing powder capacity. It will also result in higher pressure inside the case from existing powder cartridges. It is good practice to back off the powder load with heavier bullets and work your way back up until you get the right power/accuracy ratio that is satisfactory. As with all reloading tidbits, it is wise to reference overall cartridge length and powder load information from a quality reloading manual.

Shooting Considerations

For most of us, shooting different-grain ammunition will not yield a significant difference at closer distances most of the time. However, when you stretch out the distance or utilize a particular firearm, the difference can be measurable.

Let’s say you have a hunting rifle chambered in .308 Winchester and you sighted it in with 150-grain bullets. But now you want to try 168-grain ammunition because you heard about their better potential at extended distances. 100 yards is a very typical sight-in distance to zero a rifle, but it is nothing for a .308. At that distance, groups with the 168-grain load will probably shift from the point of aim slightly but in some rifles and the hands of some shooters, the difference is not enough to talk about. Only when you extend the range several times over do those heavier rounds truly shine, whereas those 150-grain rounds are really starting to drop.

The Twist Ratio Effect

But you do not necessarily have to try long-range rifle shooting to notice a difference in bullet weight. In rifles, the twist rate of the rifling inside the barrel is vital to understand to both find a pet load and know what loads to avoid. The twist rate determines how long of a bullet the barrel can spin and stabilize.

For example, some budget AR-15 rifles come with a 1:9 (one turn in nine inches) twist. This rate is excellent for stabilizing and accurately shooting bullets weighing 55 grains or less. As you go up in bullet weight, accuracy on paper can decay. My S&W Sport II rifle has that same twist rate and can put 55-grain bullets into a two-inch group at 100 yards. The groups open up some with 62-grain bullets. By the time I am shooting 69-grain or 77-grain match ammo, the group can be measured in feet, not inches.

Bullet weights can also play with the accuracy and reliability of handguns and the closer distances we expect to shoot them. Some handguns simply will not shoot lighter or heavier-grain ammunition reliably due to differences in the pressure curve that would allow the handgun to cycle.

If you aren’t shooting an autoloading pistol, lack of reliability isn’t so much of an issue as differences in point of impact. I have noticed that service-sized semi-auto pistols tend to print groups using different bullet-weight ammo close to the same point of aim. With revolvers, changing bullet weights is a great way to play with a round’s point of impact. Lighter ammo tends to hit low while heavier ammunition tends to shoot high. Many .38 Special revolvers have fixed sights that are regulated for 158-grain bullets. If you try to shoot 125-grain defensive loads or even 148-grain wadcutters, those bullets will hit low, sometimes by a few inches.

Bullet Weight: Grain Weight and a Grain of Salt

You can use grams, ounces, or grains if you wish, but understanding how bullet weight affects shooting performance is worth the weight but it also has to be taken with a grain of salt. The reloader will have to take care of his reloading setup to ensure safe loading between different bullet weights. But whether you are loading by the thousands in the comfort of the cave or buying a factory box on the way to the range, it is important to keep in mind that bullet performance based on weight can be very little or disproportionate. When it comes to bullet heft, there are few hard and fast rules, and you owe it to yourself to experiment.