Described as the “Gaza Metro,” the vast labyrinth of tunnels built by Hamas under Gaza City are employed by the terrorist organization to transport people and goods, to store rockets and ammunition caches, and notably to house the group’s command and control centers.

As Hamas lacked heavy machinery, many of the tunnels – some upwards of 100 feet below the surface – have largely been built with basic tools. However, they’ve been reinforced with concrete and wired for electricity. Israel has even accused the group of using concrete meant for civilian buildings to fortify the tunnels.

Hamas has not been shy about its efforts, however.

In 2021, Hamas claimed to have built 500 kilometers (311 miles) worth of tunnels under Gaza, and if those figures are true, it would be just shy of half the length of the New York City subway system. It presents a serious challenge for the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), which has pledged to destroy Hamas and root out the terrorist group from its rat-like maze. It isn’t expected to be an easy operation.

Yet, this is hardly the first tunnel system employed for the purposes of warfare.

In fact, the only thing that sets the Hamas tunnels apart from others used since antiquity is that this subterranean network was also built below one of the most densely populated areas on the planet – as nearly two million people live in the 88 square miles that makes up Gaza City.

Tunnel Warfare in Antiquity

As long as there have been fortifications, there have been efforts to dig under the walls – and there are Assyrian carvings that show engineering units belonging to Sargon of Akkad (2334 to 2278 BCE) undermining the walls of enemy cities. There is also archaeological evidence from the excavations at Troy that suggest passages that might have been constructed during the legendary siege.

The first truly documented tunneling effort was in the Roman siege of the Greek city of Ambarcia in 189 BCE. However, the Aetolians, who controlled the city, countered the efforts by burning feathers and charcoal to smoke the Romans out of the tunnel, resulting in the first recorded use of poison gas in warfare as well.

It is somewhat ironic for multiple reasons that the Jewish rebels in Judea during the Bar Kokhba Revolt (132-136 AD) also used tunnels to conduct an early form of guerilla warfare against the Romans. The Romans, perhaps taking a cue from its prior siege, also used fires and smoke to force out the rebels or to suffocate them to death.

It was then during the Roman-Persian Wars (256-257 CE) that mining and counter-mining operations took part under the city of Dura-Europos. Its mining/tunneling efforts on the part of the Sassanids were partially successful in damaging part of the Roman walls, but it took a ramp for the Sassanid forces to finally breach the city’s defenses. When the Romans tried to use counter-mining, the Persian Sassanid forces ignited a mixture of pitch and sulfur, killing many of the attackers.

Tunneling From The Middle Ages

The use of tunneling and mining continued during the Middle Ages in much the same way, as part of a siege effort. When a castle or other fortification wasn’t constructed on solid rock, a tunnel was dug to collapse the walls. With the advent of gunpowder, tunneling could further create a cavity under the walls, which could then be blown up.

Of course, gunpowder – and more specifically cannons – also spelled the end of massive, imposing castles. Instead of tall walls, military engineers began to construct fortifications that utilized geometric calculations that allowed defenders to better cover every possible approach. At the same time, reinforced walls and earthworks served to absorb the impact of enemy shots and shells.

These fortifications also included interior passageways, which served as storerooms during peacetime, but were garrisoned with soldiers during wartime to listen for the sounds of enemy mining efforts. To ensure that an enemy couldn’t simply dig into a fortification’s tunnel network, those internal tunnels were rigged with charges for easy collapse. Moreover, traps were often set, and some larger forts included a labyrinthine design that could easily confuse and often trap an invader. The Kremlin in Moscow was noted for having many “hearing tunnels,” which were designed to listen for enemy mines being built.

Crimean War and the American Civil War

Tunneling fell out of favor during many of Europe’s wars of the late 18th and 19th centuries as invading armies often bypassed major fortifications. However, tunneling was employed again during the Anglo-French siege of Sevastopol during the Crimean War (1854-1855), and due to counter-mining efforts, the Allied forces began to dig deeper. When they hit rocky ground, they were forced to return to a higher level.

It was truly horrible conditions – sappers (the miners charged with digging the tunnels) had to deal with stale air, and groundwater that often flooded the tunnels while there were numerous cave-ins. Worst of all for the diggers, the tunnels failed to help break the siege.

A decade later, during the Siege of Petersburg in the American Civil War, the Union Army of the Potomac dug a mine that was filled with 3,600 kg (8,000 pounds) of gunpowder and it was detonated under the Confederate defenses. It created a crater that was 52 meters (170 feet) long, 37 meters (120 feet) wide and at least nine meters (30 feet) deep. The subsequent fighting was known as the Battle of the Crater. Though it seemed to initially give the advantage to the Union Army, the Confederates managed to repulse the invading forces.

A similar scene played out at the Siege of Vicksburg where a tunneling effort with a mine beneath the defenses resulted in a larger crater and the Union Army was able to briefly gain a foothold before being driven back.

Despite the lack of success from mining/tunneling during the Crimean and American Civil Wars, tunneling continued.

Tunneling in the 20th Century

Though Chinese military theorists had discussed since the days of Sun Tzu how tunneling and mining could be employed way to surprise an enemy, it was actually during the Russo-Japanese War (1904-05) that the Japanese attempted to dig under the Russian fortifications at Port Arthur. The Japanese called upon thousands of diggers, who dug hundreds of tunnels that were packed with explosives.

In this case, tunneling did prove far more successful, and that may have encouraged its use a decade later during the First World War when it was employed in an attempt to breach the lines of the Western Front.

The region around the Ypres salient of the Western Front proved well suited for tunnels, and the British Army’s Royal Engineers even created tunneling companies. By mid-1916 there were some 25,000 trained “tunnellers” – mostly volunteers who had been coal miners. In addition, almost twice that number of “attached infantry” served alongside the miners as “beasts of burden” to move dirt and other material.

As with many of the efforts to break the stalemate, tunneling offered mixed results.

It was on June 7, 1917, that a mine filled with 440 long tons of explosives was detonated beneath the German lines near Hill 60 on the Western Front near the Belgium-French border. The blast created one of the largest explosions in history and reportedly was heard as far away as London and even Dublin. It demolished a significant part of the German defenses and killed upwards of 10,000 – yet it didn’t break the German lines.

Moreover, due to so much tunneling by both the Allies and the Germans, there were times when each side would break through into the other’s tunnels. This resulted in vicious hand-to-hand fighting – with picks, shovels, and even rocks.

Tunneling wasn’t very widespread in the Second World War in Europe, apart from efforts by soldiers to dig tunnels to escape from POW camps – as seen in such films as “The Great Escape.” It also wasn’t just the Allies that dug tunnels either. Twenty-five German POWs tunneled out of Camp Papago Park, near Phoenix, Arizona, in December 1944. It was the largest breakout of German prisoners during the war, but all of the escapees were eventually recaptured.

It was a different story in the Pacific, where the Japanese built tunnels to offer protection from observation and aerial attack, as well as to enhance the defenses. This was especially true on the volcanic island of Iwo Jima, where the Japanese dug a massive network of tunnels, and it contributed to what was certainly one of the bloodiest battles in the history of the United States Marine Corps as the Japanese were so well entrenched within the very island.

The Vietnam War and Tunnel Rats

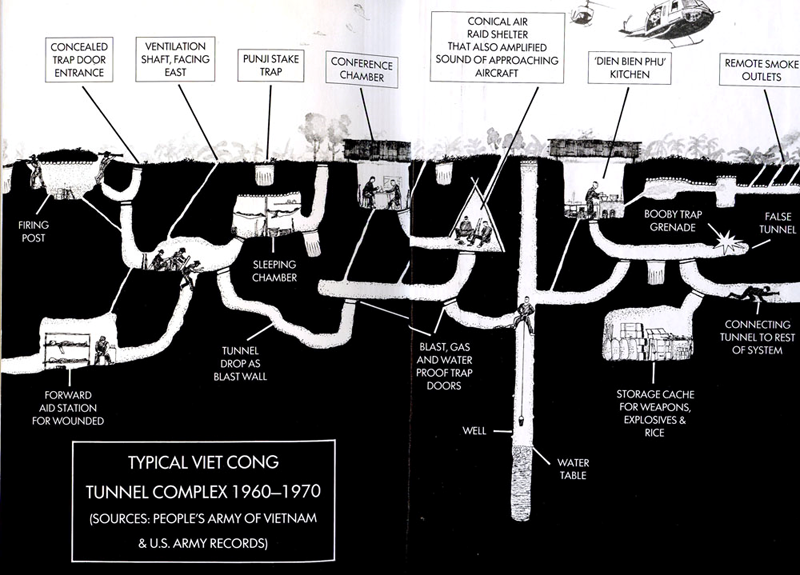

It was during the Vietnam War that the U.S. military again had to deal with vast tunnel systems. The Viet Cong (VC) guerrillas proved especially resourceful at constructing the underground networks, and one of the largest was in the Cu Chi province near Saigon. The maze of tunnels offered shelter from U.S. aircraft, but also enabled the guerrillas to conduct hit-and-run style raids. Heavy equipment was eventually employed to destroy the underground complex, but the VC rebuilt the tunnels.

Today, those tunnels have been transformed into a tourist attraction!

The tunnel issue became so great in Vietnam and Southeast Asia that the U.S. military called upon “Tunnel Rats” – those trained in penetrating and searching VC tunnels. Some were able to conduct dozens of incursions in the dark with little more than a 1911 handgun and flashlight, but others found the missions to be extremely taxing.

When a Tunnel Rat announced that he could no longer perform the mission, there was little questioning by their superiors. Everyone simply understood the difficulty of the job of rooting out the enemy under the ground in the dark. It was not a task most could do for long.

Tunnels in Afghanistan and Ukraine

As the American military pursued Al Qaeda and Osama bin Laden following the 9/11 terrorist attacks, it discovered a massive tunnel complex that connected the natural Tora Bora cave formations in Afghanistan. Within that vast network of passageways were hospital facilities, storerooms, electronic communications equipment, and even climate control systems that could filter chemical contaminants.

While the U.S.-led coalition forces achieved a tactical victory in capturing and destroying the tunnels, it was largely a strategic failure, as the Al Qaeda fighters and their senior leaders – including bin Laden – escaped. In addition, little useful intelligence was captured by the coalition troops. The tunnel complex was destroyed, but the Taliban soon reoccupied much of the region.

Tunnels and underground bunkers are now being employed by both sides in the ongoing war in Ukraine.

Some were built by the Soviet military under major population centers, while others were actual mines or catacombs – some without any formal maps! These tunnels aided in Ukraine’s defense following Russia’s unprovoked invasion in February 2022, but now the Kremlin’s forces are also using tunnels to slow Kyiv’s counteroffensive.

Hamas and Hezbollah Tunnels

Both of Israel’s primary adversaries – Hamas in Gaza and Hezbollah in southern Lebanon – have each built massive tunnels, some of which cross into Israel proper. As noted, the “Gaza Metro” could present serious challenges for the IDF as it seeks to clear out the terrorist organization.

And as long as there are conflicts, tunnels will continue to present problems for Israel and beyond.