The early 1700s were the time of flintlock rifles and ponderous cannons, especially at sea. The British Royal Navy was the world’s most powerful and, combined with a brisk economy, was well on the way to providing Great Britain with a truly globe-spanning maritime empire, the largest in history. But even the top dog occasionally has trouble. That trouble inspired a revolutionary new firearm known to history as the Puckle Gun.

Those Pesky Pirates

The 18th century’s first two decades fall well within the so-called “Golden Age of Piracy.” Though that term generally conjures images of European and North American pirates like Benjamin Hornigold and Edward Teach, aka “Blackbeard,” pirates from Ottoman Turkey and Africa’s Barbary Coast terrorized the Mediterranean World and even ventured into the Atlantic Ocean.

The Ottoman pirates, in particular, troubled British merchant ships, and by extension the Royal Navy, by attacking in small, fast, maneuverable boats that could avoid the heavy cannons plied by the British Men o’ War. The problem was so pronounced that an English lawyer named James Puckle, who may or may not have also been an inventor, introduced a never-before-seen repeating firearm known today as the “Puckle Gun.”

The First Machine Gun?

The Puckle Gun is sometimes inaccurately hailed as the world’s first machine gun. To be fair, a 1722 shipping manifest lists “2 Machine Guns of Puckle’s,” and the patent itself refers to the gun as “the machine.” But it operated quite differently from modern machine guns. The gun is more accurately described as a repeater, more along the lines of a revolver than a machine gun. But in a time of single-shot muzzleloaders, the Puckle Gun’s fire rate bordered on the miraculous.

London lawyer and businessman James Puckle offered the gun to the Royal Navy in 1717 as a counter to the fast pirate boats. The fast-firing weapon, very well balanced on a tripod or rail-mounted pintle, would have been ideal for raking small, fast, raiders. Despite the gun’s impressive design, however, the Navy passed after testing it. They felt the flintlock firing mechanism was unreliable, especially in a maritime environment. Plus, the gun featured many unique parts that required careful workmanship. The Navy decided it was not suitable for mass production and thus not affordable.

Puckle the Salesman

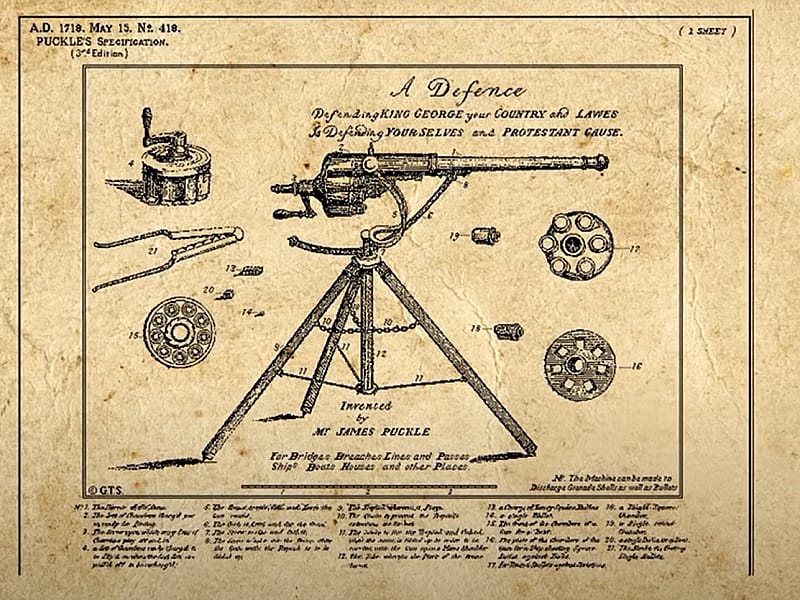

Undeterred, Puckle patented an improved version, called the “Defence,” in 1718. Ever the salesman, Puckle wrote the following on the patent drawings: “Defending KING GEORGE your COUNTRY and LAWES – Is Defending YOUR SELVES and PROTESTANT CAUSE” That last shows that Protestants and Catholics were still quite sore at one another over the previous century’s Thirty Years’ War and the ongoing rivalry between the two religious camps.

The patent drawing also noted that the gun was designed “For Bridges Breaches Lines and Passes Ships Boats Houses and other Places.” Puckle clearly believed that the Army, as well as the Navy, could benefit from his gun.

The Puckle Gun’s most famous demonstration, in 1721, saw it fire 63 rounds in only seven minutes. That’s absolutely unheard of in a time when flintlock muskets were top-of-the-line weapons. One of the gun’s ingenious features, which allowed such performance, lay in its easily changed preloaded 6 or 9-chamber cylinders. This demonstration would have consisted of seven 9-chamber cylinders, which breaks down to one cylinder per minute. A trained soldier could, at best, fire three musket rounds per minute.

Another amazing aspect of the demonstration was that it rained the whole time. An observer wrote that “[O]ne man discharged it 63 times in seven Minutes, though all while raining, and it off either one large or sixteen Musquet Balls at every discharge with great force…” Note that the gun could fire single 1.25-inch musket balls, or 16 smaller balls, like a shotgun.

If that report is accurate, one might think that the Navy’s concerns about the flintlock mechanism were wrong, but we do know that Puckle had updated the design since the trials. Either way, he had not addressed the mass production difficulties, which is likely what sunk the design in the end.

How the Puckle Gun Worked

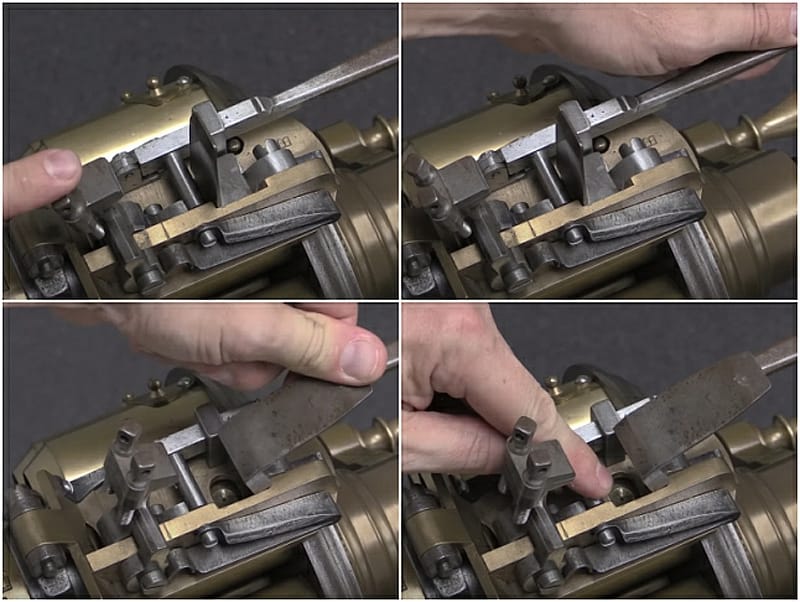

As noted, the Puckle Gun was akin to a revolver, but with the 6 or 9-chamber cylinder preloaded and attached before firing.

- Each cylinder chamber was loaded with ball or shot.

- The cylinder was mounted onto a threaded axle and screwed into place with a hand crank.

- As with a revolver, a chamber was aligned with the barrel. Each chamber was tapered to match the barrel, creating a gas seal. The gunner inserted the chamber into the barrel by cranking it down on the axle.

- The gunner then activated the trigger lever, releasing the flint equipped hammer, which sparked on the frizzen, igniting the preloaded powder and firing the gun.

- The gunner then cranked the spent cylinder out of the barrel, rotated the cylinder to the next chamber, and repeated the process until all cylinders had fired. Rotating the chamber automatically pushed back the cover protecting the priming pan, which kept the powder dry and in place.

- Extra cylinders could easily be stacked nearby.

Interestingly, the Puckle Gun’s cylinder sealing system makes it like a particular revolver: the Nagant M1895. Unlike standard revolvers, the Nagant’s cylinder moves forward upon cocking to create a gas seal.

The patent drawing also shows a cylinder with seven square chambers, as opposed to the normal round ones. Puckle said that the square projectiles were to be used on Muslims to “convince the Turks of the benefits of Christian civilization.” Assuming it was possible to fire square shot through a round barrel, one can see where the square projectiles would be even more damaging to anyone unlucky enough to be hit by them. Puckle also noted that only round projectiles should be used on Christian foes.

Did James Puckle really invent the gun?

The Institute of Military Technology Director Joe McClain questions whether Puckle actually invented the gun, even though the patent clearly states that he did. It’s a fair question. After all, Puckle was a lawyer by trade, but he was also involved in many business dealings.

McClain asks, however, whether Puckle had any background in machining or gunsmithing. If so, there’s no record of it. Some historians believe that Puckle either bought the rights to the design or even stole it outright. These same historians point out that advanced mathematics and/or machining skills would be required to design and build the Puckle Gun. Puckle himself does not appear to have possessed those skills.

It was noted, says McClain “in the October/November 1721 Daily Courant newspaper that Peter Hartopp, Esq. would be paid two shillings per share for the number of guns sold.” Now, it could be that Hartopp bought shares in Puckle’s company, which we know he founded to market and sell the gun. Or it could be a royalty payment.

McClain mentions another interesting theory advanced by historians. It seems that the office address of “Inventor James Puckle” was in Whitecross Alley, Moorfield, London. That was also the address of foundry owner Matthew Bagley. Bagley and his son were killed in a mysterious “damp mold explosion” at the foundry just before the patent was approved. The implication here is that Puckle got the design from Bagley, then had him killed. A serious charge, indeed.

Of course, there’s no way to know. But the gun’s ingenious design and masterful workmanship do seem to be beyond the capabilities of a lawyer and financier.

McClain offers one more intriguing tidbit. The Puckle Gun was mounted on a very well-designed and functional collapsible tripod, yet the tripod itself was never patented or marketed separately from the gun. If it had, it would have been the very first of its kind and likely very successful.

An Ultimate Failure

As it turned out, Puckle only ever sold two guns. That’s it. John Montagu, the 2nd Duke of Montagu, purchased those two guns in his role as the British Master General of Ordnance. King George had granted Montagu the Caribbean Islands of St. Vincent and St. Lucia, whose ownership was disputed by France. Montagu sent the guns with the seven-ship expedition to colonize the islands. The 1722 manifest mentioned earlier referred to these two guns. Lacking Royal Navy support, the French soon ejected Montagu’s settlers.

Those two guns are the only all-original Puckle guns in existence today. They are housed in two of the duke’s former homes, Boughton House and the Palace of Beaulieu. A third Puckle Gun, containing some original parts, along with some reproductions, may be viewed at the Institute of Military Technology in Titusville, Florida.

Probably the fastest-firing weapon in the world, designed for naval ships but certainly capable of other uses, just didn’t sell. Based on the three examples we have today, the Puckle Gun was extraordinarily engineered, seems mostly reliable, and the design is quite ingenious. The workmanship looks fantastic.

But the Puckle Gun seems to have been ahead of its time. The concept was sound and the design and workmanship were impressive. But the infrastructure to mass produce the gun did not yet exist. Without that capability, each gun would have to be built individually, requiring many man-hours, and ultimately making it prohibitively expensive. So, all we have are three might-have-beens. But we have to say, successful or not, the Puckle Gun is pretty awesome.

The ever-knowledgeable Ian McCollum has a great video demonstrating the Puckle Gun’s functions on his Forgotten Weapons YouTube Channel. Check it out.