“In Congress, July 4, 1776. The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America.”

The Declaration of Independence opens with those lines. The wording is significant. The Continental Congress’s previous correspondence with King George III had taken a different tone entirely:

- 1774’s Articles of Association opened with “We, his majesty’s most loyal subjects, the delegates of the several colonies of…”

- 1774’s Petition to the King began, “We, your Majesty’s faithful subjects of the Colonies of…”

- 1775’s Olive Branch Petition started with “We, your Majesty’s faithful subjects of the Colonies of…”

The delegates of the Second Continental Congress, for the first time, addressed themselves to the king not as subjects, but as free men.

The Road to July 4, 1776

The colonies had been at war for over a year by the time the Declaration was adopted and signed. The American Revolution went hot on April 19, 1775, at Lexington and Concord. The Americans took Fort Ticonderoga and besieged the British garrison in Boston shortly thereafter. Congress soon dispatched George Washington to take command. The Battle of Bunker Hill raged on June 17 of that year.

Congress signed the Olive Branch Petition on July 8, 1775. It was a last-ditch attempt to peacefully resolve the colonists’ differences with the British Crown. The petition fell on deaf ears and the fighting continued. The British repulsed the Americans at Quebec at year’s end and Washington was fighting on Long Island the day the Committee of Five presented the Declaration’s first draft to Congress.

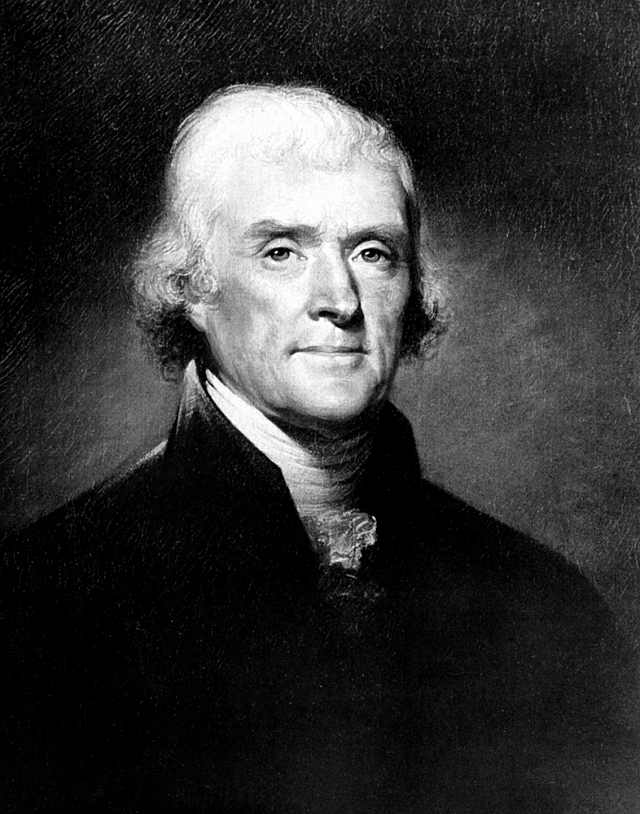

Virginia Delegate Richard Henry Lee, on instructions from the Virginia legislature, presented a resolution “That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent states…” on June 7, 1776. Congress voted to delay debating the resolution for three weeks. John Hancock, President of the Second Continental Congress, appointed a “Committee of Five” to draft a declaration of independence for the Congressional “Committee of the Whole” to consider. The committee chose Thomas Jefferson to compose the declaration.

The Committee of Five presented the proposed declaration to Congress on June 28, sparking a marathon debate. The declaration underwent several significant changes before final adoption on July 4. Most people believe the Declaration of Independence was signed on that date, but Hancock didn’t attach his famous signature until August 2, followed by most of the other signers. Others signed even later, with several not doing so for months or even years. July 4 signifies the day the Declaration was adopted and approved to be printed on engrossed parchment, which took time.

A Deeper Look at the Declaration of Independence

A long list of specific grievances against King George III is front and center in the Declaration of Independence. They foreshadow the ideals found in the Constitution and Bill of Rights. But the Declaration’s introduction and its final sentence are far more memorable.

“When in the Course of human events…”

The introduction’s first sentence, which is really a short paragraph, clearly changes the Founders’ allegiance from the British Crown to “the Laws of Nature and…Nature’s God.” Americans, and their rights, were no longer subject to the whims of kings, but to Nature, as truly free citizens should be. This concept led to the Constitutional protection of such rights, instead of claiming to grant them.

“We hold these Truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness…”

This paragraph later asserts that governments are “instituted among men” to secure those rights. Again, the concept of governmental protection of rights. It also addresses the right and the duty of the People to throw off any government that “becomes destructive of these Ends.”

The Founders caution against changing a government for “light and transient Causes.” They knew that such actions lead inevitably to turmoil and should only be undertaken when a government, after “a long Train of Abuses and Usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object, evinces a Design to reduce them under absolute Despotism.” The People are then compelled “to provide new Guards for their future Security.” There’s the protection of rights concept one more time.

“And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm Reliance on the Protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes, and our sacred Honor.”

Those weren’t empty words. Every one of them would have a date with the hangman for high treason should the Revolution fail. They all knew that but did it anyway. Rhode Island Delegate Stephen Hopkins supposedly said, “my hand trembles, but my heart does not,” as he signed the Declaration. Delegate Benjamin Harrison reportedly joked that should they hang, his being overweight meant that he would die quickly, while the thinner Elbridge Gerry would “kick in the air half an hour after it is over with me.”

Unlike today, statesmen were actually a thing in 1776. They were also politicians, but more than mere partisanship drove them. They also understood the importance of a united front. The delegates decided that the decision for independence must be unanimous. Otherwise, the motion would fail.

The delegates knew the Crown would use even one dissenting vote to undermine the others, creating internal conflict that would sink the entire enterprise. They only achieved that unanimity through compromise. More on that in a moment. Benjamin Franklin noted that “We must, indeed, all hang together, or most assuredly we shall all hang separately.”

But it wasn’t all jocularity. In an 1811 letter to John Adams, Delegate Benjamin Rush asked, “Do you recollect the pensive and awful silence which pervaded the house when we were called up, one after another, to the table of the President of Congress, to subscribe what was believed by many at the time to be our own death warrants?” Their courage is remarkable.

Unity also influenced how the delegates signed the Declaration. When signing the aforementioned Articles of Association, Petition to the King, and Olive Branch Petition, the delegates all included the colony from which they hailed. Not so on the Declaration of Independence. They signed on behalf of the citizens of “the thirteen united States of America.” No longer Royal Colonies, but a new and unified nation. A significant difference indeed.

Omissions and Compromises in the Declaration of Independence

Politics and diplomacy are about compromise. Unless it’s gun rights. Then only one side gives, and they all call it “compromise.” But I digress.

“Remember the Ladies”

Abigail Adams famously asked her husband, John, to “remember the ladies and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors.” John either did not or could not honor her request, and it took almost 150 years before the 19th Amendment recognized women’s right to vote. Her entreaty was one of the first steps toward women’s rights in America.

The Slavery Conundrum

The Declaration’s first draft attacked slavery as “a cruel war against human nature itself.” Jefferson and the other Committee of Five members apparently believed the phrase “all Men are created equal” applied literally to all men. We can wonder how ardently Jefferson believed that considering his failure to free his own slaves in years to come, but it was included in the initial draft.

The slavery issue was the wedge that most significantly threatened unanimity. According to Jefferson, the South Carolina and Georgia delegations vigorously opposed the slavery clause. But one “no” vote, much less two, would kill the Declaration.

No record exists of the reportedly intense debates over slavery. It seems that economic interests, North and South, drove the delegates to strike the slavery clause. South Carolina delegate Edward Rutledge initially opposed independence. But he seems to have convinced his colleagues to vote yes once the clause was removed. The Southern states forced the same compromise when the Constitution was ratified in 1787. Slavery remained in return for supporting votes.

Modern commentators routinely criticize the Founders and the Framers for those choices. They faced similar charges of hypocrisy in their own day. That slavery was a blight on the nation cannot be denied, but both groups were astute enough to do what they could when they could. The compromises were bitter but seemingly necessary. The nation paid a heavy toll later, but men who understood that all or nothing is rarely a good choice in matters of policy began the process in 1776.

The Declaration of Independence as an Example

We obviously celebrate Independence Day as the birthdate of the United States of America, as we should. Yes, there are some ugly parts to our nation’s history. Just like every other nation in the world. But, in 1776, a rare group of men gathered in Philadelphia and produced an extraordinary document pointing us toward our highest aspirations.

We often fall short of those aspirations. That’s what humans do. But the United States, since its inception, has served as a beacon of what we can be, often in spite of ourselves. There’s a reason that so many millions of people have literally risked their lives to come here, leaving behind everything they’ve ever known. It’s also telling that so few people actually leave to go somewhere else, despite their rhetoric.

Abraham Lincoln famously called the United States “the last best hope of Earth.” It’s sometimes hard to see that today. But Lincoln wrote those words in the depths of the nation’s worst crisis. The division was far worse than it is now. Lincoln persevered nonetheless and the crisis of civil war eventually passed.

This Independence Day, we could all benefit from the Founders’ example of unity. They did what they could when they could and had faith in the future, pledging their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor to one another. We must find a way to do the same, because if we don’t, “most assuredly we shall all hang.” Together or separately.

Happy Independence Day. Join me in raising a glass to the 56 men who showed true guts on this day 246 years ago. Well done, Gentlemen. Well done.

Note: Capitalization rules in 1776 were more like guidelines. I have rendered quotes faithfully, grammatical errors and all.