“Senior Sergeant Shanina, during a breakthrough deep into the enemy defenses on the border of East Prussia during the invasion of East Prussia, took an active part in the battles in support of the advance infantry, fired accurately to eliminate Nazi soldiers and officers…Comrade Shanina showed exemplary courage and valor, with her presence, as a girl, showing the soul of a true fighter of fortitude and courage, driving accurate fire on the Nazis.”

So reads Roza Shaina’s citation for the Red Army’s Medal for Courage, awarded on October 27, 1944. The 20-year-old sniper was credited with over 50 confirmed kills by that time, less than seven months after her first kill on April 5. It was Shanina’s third decoration, having earned the Order of Glory 3rd Class in April and the Order of Glory 2nd Class in September. She was the first female sniper to receive the Order of Glory.

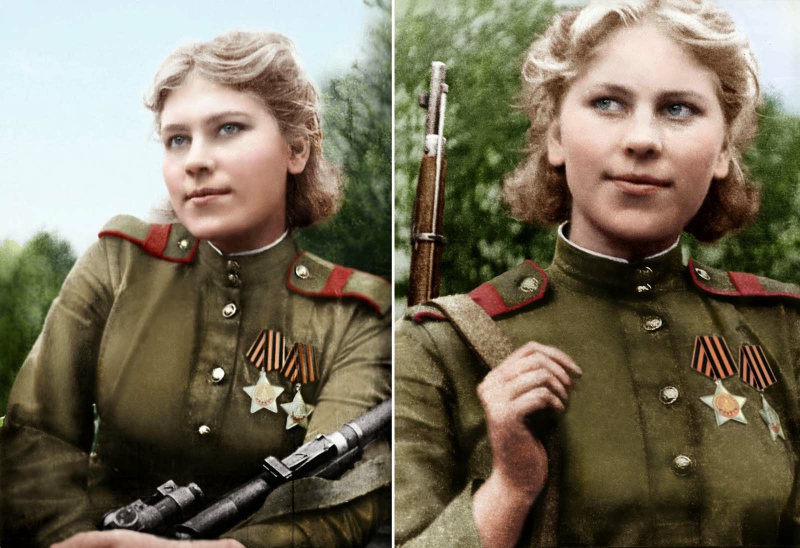

Commanding an all-female sniper platoon, Roza was a national hero, her photos appearing in Soviet newspapers and magazines. A Canadian newspaper called her “the unseen terror of East Prussia.” Roza also wrote regularly to war correspondent Pyotr Molchanov. Her letters express frustration that her unit was posted to the rear, and she asked Molchanov to speak to the command on her behalf. She desperately wanted to fight the invading Germans at the front.

In her letter of August 8, 1944, Shanina wrote that “I recently went AWOL. Carelessly left the rear for a company at the front. Good people have said that leaving from the rear to go to the front is not a crime…I also need to be at the front, to see with my own eyes what it is, a real war…All around the forests and swamps, staggered Germans. It was a dangerous walk. I went to the battalion, which was directed to the front, and on the same day fought in the battle. Beside me, people were dying. I fired, and successfully. And afterwards captured 3…these fascists are strong. I’m happy I went AWOL. Although they reprimanded me.”

From Kindergarten Teacher to Deadly Sniper

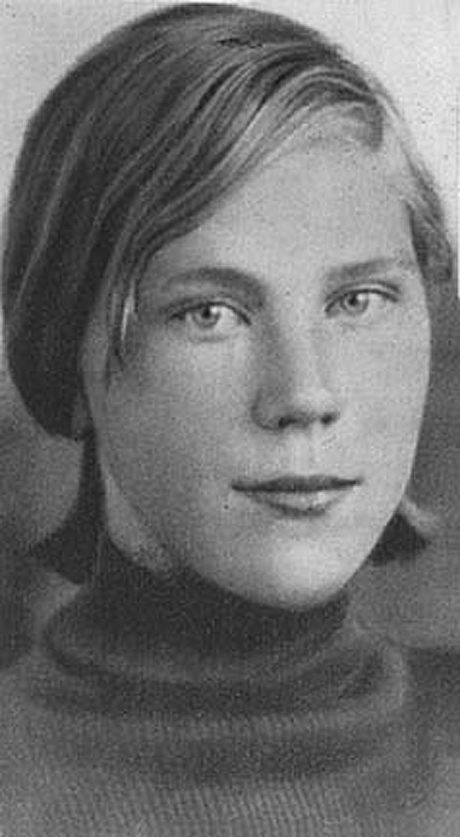

Roza Shanina was born on April 3, 1924, on a collective farm in northern Russia. Her father was a Communist party official who had served in the First World War. At age 14, after seven years of schooling, Roza asked to attend secondary school to study literature. When her family balked, Roza ran away, walking 200 kilometers to the village of Konosha, where she caught a train to the Arctic port city of Archangel.

Roza lived there with her older brother, Fyoder, while studying for the school’s entrance examinations. She was accepted and provided with a stipend and living quarters. Roza was studying to become a teacher when Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941. The Soviets were caught completely by surprise and their economy collapsed. All educational stipends were revoked, and Roza took a job at the nearby kindergarten to finance the rest of her education.

Roza took classes during the day and taught in the evenings. She graduated with honors in the spring of 1942. She then entered the Archangel Pedagogical Institute to become a fully qualified teacher. German bombers soon began attacking the Archangel docks, and Roza volunteered for night air raid duty, carrying water to combat the fires.

Roza’s brother, Mikhail, had been killed in the Siege of Leningrad in December of 1941. She tried to join the Red Army immediately after, but she was too young. But by the summer of 1943, Roza was determined to fight. Her supervisor at the kindergarten, T.V. Kurochkina, recalled that Roza informed her of her decision to enlist, staring “with eyes that could throw sparks off steel.” Roza joined the army on June 22, 1943, exactly two years after the German invasion.

Roza excelled in her basic training and was recommended for sniper school, where she once again graduated with honors in the spring of 1944. She was offered the chance to stay as a sniper instructor but refused, wanting to fight the Germans. She was promoted and given command of the 184th Rifle Division’s all-female 1st Sniper Platoon. On April 5, two days after her 20th birthday, Roza Shanina killed her first German soldier. Her regimental commander’s report noted that she went on to kill 13 enemy soldiers between April 6 and April 11, despite being under artillery and machine gun fire. On June 9, 1944, Roza’s photo was featured on the front page of the Red Army newspaper Destroying the Enemy.

Running Away to Hunt Germans

But the female snipers were withdrawn from the front in June 1944, right as Operation Bagration, the massive Soviet spring offensive, kicked off. Roza resented the withdrawal, and soon began slipping away and walking to the front lines. Sometimes she hitched rides in trucks or tanks. Despite Roza’s hard work in school, such things were characteristic. She had run away to attend secondary school. And while there, she frequently missed curfew, climbing back into her dorm room using knotted sheets thrown down by her friends.

But in late summer of 1944, Roza got her wish. In an August 31 letter to Molchanov, she wrote, “Thank God, finally we are back in the fight. All went to the front. Score increases. I have the most [among her platoon] – 42 dead little Hitlers.” Running away to the front was apparently productive.

Roza’s Diary

Roza began keeping a secret diary in October, though it was strictly against orders. Perhaps her literary studies compelled her to write, though her form is often clipped and sometimes hard to follow. Frankly, she probably had little time to write, especially doing it secretly, and just jotted her thoughts down as she had the occasional moment.

The diary is fascinating, oscillating between hard bitten warrior openly yearning for combat and the 20-year-old girl longing for girlfriends and an ever-elusive male companion. Roza’s diary entries reveal a young woman of high personal standards, who complains of even her platoon mates only wanting to be her friend when she is in the media spotlight but ditching her otherwise. She often criticizes them for sleeping around while claiming to still be maidens.

Roza goes through a series of boyfriends herself, though she herself claims to be what she describes as “a girl,” presumably meaning a virgin. Still, some accounts make one wonder, if only because of their vagueness. But she almost always finds the men’s character wanting.

She writes that she “really likes” Lt. Nikolai Shevchenko. “He is in love with me,” she continues, “but he’s not very tall, and I don’t like even a little shorter than me, and so I suffer for it.” Her relationship with Lt. Shevchenko soon sours. Only a few days later, Roza writes, “Worried about Nikolai. He disgusted me, and he acted very badly: wanted to get drunk…and take advantage. I can’t stand it.”

She was also upset that the lieutenant had been instructed to send Roza to meet with a Moscow photographer along with some unnamed generals. “But Nikolai did not want me to leave and did not tell me that I was called.” Roza describes being “scolded” by the generals, so that probably didn’t help Nikolai’s cause.

Around the same time, Roza writes of a soldier she loved “like a little brother,” but who apparently came on pretty strong. “Flashed my dagger,” in response, Roza writes. “I do not understand anything, even life, it’s all so intertwined.”

Red Army soldiers were largely illiterate, and what manners they had would have seemed crude to an educated young woman. Roza herself was a pretty girl and no doubt attracted many suitors, especially soldiers starved for female companionship. Her wandering among the various front-line units meant she came in contact with many such soldiers, and she was rarely in one place very long.

She often describes warm welcomes from the men at the front, soon followed by crude suggestions and even unwanted physical harassment. But through it all, her desire to get at the Germans is driven home. Her writing sometimes pivots straight from her relationship woes to wishing she could kill more Germans.

“Not Frightening”

The diary’s October 12, 1944, entry reads “I want to be at the front, it’s simultaneously interesting and dangerous, but not frightening to me for some reason.” The same entry later describes a German air and armored attack on her position. “Just to the left of me, 8 meters away,” Roza wrote, “a tank crushed a lieutenant and a captain, and other soldiers. My rifle jammed. Quickly, I cleared the jam and shot again. Here comes the tank directly at me, 10 meters away. I feel for my grenades – but they were lost while crawling through the rye. And I was not scared.” The Germans bypassed Roza’s unit, surrounding them in a pocket. She wrote that “after everything, when I saw the dead and wounded, it was terrible. Before his death, the captain gave me a watch.”

Roza’s unit held out and was relieved by advancing Red Army forces two days later. A lieutenant of that unnamed unit, she wrote, “continued to make passes at me. I took my rifle, grenades, and went to seek a place with room for outraged feelings.” She admits to crying a lot. Her division had apparently been rotated off the line because she was kicked awake the next morning by two soldiers sent to find her and bring her back. She went begrudgingly.

A Rare Insight

Roza’s diary provides a rare insight into the thoughts and experiences of a female combat soldier. Such accounts are few and far between. Roza pines for friendship, a man who meets her standards, and always a chance to fight.

Roza’s closest friends at the front seem to have been a pair of fellow snipers: Alexandra “Sasha” Ekimova and Kaleria “Kalya” Petrova. They appear regularly from about the middle of November 1944 until the diary ends in late January 1945. Even so, Roza seems to hold them at arm’s length at times, though she constantly wishes for friends.

Always ready to fight, Roza writes on November 26, 1944, that “I understand the thirst of my life – battle.” The next day, she writes of how German soldiers captured two members of her platoon by sneaking up on their position and dragging them away. Their fate was reported by a third woman who escaped by playing dead.

“Are the other two still alive somewhere?” she wonders. “Here now are German women to take revenge on [the Red Army was in German territory by this time] but I don’t have the heart to do it…Surprising, but I was told bluntly that I can now kill not only Germans [soldiers], but whoever, as I was ordered. I cannot. I lived such a life, and I cannot spoil the serene atmosphere [Hitler had refused to allow German civilians to evacuate as the Red Army advanced]. I crave war, in the present minutes it gives happiness to my life, but after it’s finished?”

The December 6 entry reads, in part, “You know, throughout my life at the front there was not a moment when I didn’t long for a fight; I want a fierce fight, want to go with the soldiers…I’d give anything to go with the soldiers now. Oh Lord, why do I have this mysterious nature? I just can’t understand, all I crave, crave a fight, a fierce fight. Everything I will give, and life, simply to satisfy this urge. It torments me, I cannot sleep.”

This entry is among the diary’s longest and most detailed. Roza writes of someone named “Alkimova,” who wrote that “I don’t believe Roza has killed as many Fritz [Germans] as she gets credit for.” Her response is thoughtful: “Maybe so. In my defense, sometimes I shoot at a lot of targets, but it’s dark, and it’s hard to tell if it was a kill or not. To be fair, I always accurately target and hit a standing Fritz, and more often get a kill than in the past. And in most cases, I’m shooting at stationary targets or marching soldiers. Deserters are hard, just scare them. Sometimes I don’t write them down, sometimes I guess, sometimes no kills, but to look to my count and say I haven’t killed any Fritz, it’s false.”

Roza further describes an unnamed engagement in which she fired 70 rounds helping to blunt a German counterattack. “In the attack I was against 13 tanks, at 3 I did not shoot, but I killed 9 in all.” Whether she means she killed 13 tanks, or 13 men is not entirely clear, though she later mentions that she “wounded at least 20.”

But what makes this account interesting is that Roza mentions she was firing the Model 1870 Berdan rifle. This had been the standard Russian infantry rifle before being supplanted by the 1891 Mosin Nagant. Roza’s usual weapon was the sniper version of the Mosin Nagant 91/30. But here she used the old Berdan, apparently in an anti-materiel role, which is certainly not out of the question given the Berdan’s massive 10.75x58mm rimmed cartridge. That’s a .42 caliber rifle round. Roza’s further commentary seems to indicate she was operating against self-propelled guns or, perhaps, halftracks as opposed to actual tanks.

“One went through back to the driver, killed, and the other soldiers were hit and injured by the bullets, or something, from the Berdan rifle, which was covered in mud. Did not have time to find targets or aim. And I hit at 50 to 7 meters at close range. I went prone and wounded at least 20. In the attack I often had to shoot precisely at close range and not miss.”

Roza the Enigma

On December 7, Roza had apparently had enough of not being officially posted to a line unit. She wrote a letter directly to Soviet dictator Josef Stalin, asking for a transfer. She apparently continued her habit of slipping away to the front, because she was wounded on December 12, when a German sniper shot her in the shoulder.

By December 17, she was looking to return to combat. She wrote to Molchanov from an army rest home that she did not want to return to her old sniper platoon because “it’s still too quiet there. I already want to work again. This is my need, instinct. How do you explain that? Well, you know, I long for battle every day, every minute. I can be more useful for our common cause.”

While in the rest home, Roza wrote to her friends and read several books. She wrote on December 27 that “When my life is good, I don’t want to write.” She does, however, write quite a bit about the books she read and how they affected her. Roza seems to have been deeply moved by literature and poetry, a strange juxtaposition to the stark warrior who craved combat.

This same entry describes her going for a walk, during which she “bumped into a sweet little boy. ‘Let me give you a kiss [the boy said]. I’m 4-years-old and I haven’t kissed a girl.’ And he asked so earnestly, I got sentimental. And really, so cute, not nasty, but nice. ‘To hell with you – I say – kiss me, just one time.’ And I nearly cried. Why? From compassion.” Roza the kindergarten teacher was still there, despite the war.

The entry includes several quotes from books she had recently read. I find them interesting, if for no other reason than their variety, which further speaks to Roza’s complex nature.

From the book Princess Heart: “Love stands strong, it gives beauty where there is none, and forges chains which no spell can break.”

From the book Sister Carrie: “Oh passion, passion! Oh blind strivings of the human heart! Onward, onward, it saith, and where beauty leads, there it follows.”

From the book Bagration: “This is the meaning of glory – this or his skull split in the name of the Motherland, or until another’s crumbles – Here is glory!”

From the book The Story of My Life: “You would bind my will with your laws? The law makes a crawling snail of those who would take off in an eagle’s flight.”

Roza closes the entry with a rather long bit of poetry under the Titles My Love and Beloved. I don’t know whether she composed them herself or they were merely lines that spoke to her. But, again, they seem quite opposed to the Roza who craves war.

Sustained Combat

Roza returned to the war on January 8, 1945, when her request for frontline service was finally granted. She was posted to the Soviet 5th Army after a personal interview with the commanding general, Colonel General Nikolai Krylov. Roza shares that she persuaded the general “with great difficulty.”

She returned just in time for the massive East Prussian offensive. By January 13, Roza writes of heavy combat and sleeping on a pallet in a low, noisy, smoke-filled dugout. She writes that she was “Freezing, in wet boots, in frozen boots. Everyone takes coats, but I’m a northerner, and don’t need one; it is hard to walk.”

Even with her reputation, Roza endured certain prejudices. “I’m taken as a notable sniper,” she writes on January 16, “it seems that’s the only reason that I’m accepted. But everyone feels that I came because I have a man in this division. The regimental commander even asked this question. I decided not to love anyone, and all are disappointed. I came, I don’t know a single soul. I endure dirt, cold, hunger. All advise…that I should return to the platoon, instead of suffering such a war: shooting, the rattle of death in every minute of my life.”

Roza still drew national attention. Destroying the Enemy touted her exploits, and her photo graced the front page of the Moscow journal Spark. “I’m showered with glory,” she wrote, “Imagine, the whole country reads it, all my friends, and who will know what I feel at this moment.” The Russian poet Ilya Ehrenburg wrote of Roza as among the Red Army’s most notable snipers, saying, “57 times in succession thank her, thousands of Soviet lives she saved.”

Roza’s response in her diary is as enigmatic as ever: “And I thought to myself – this is really glory. ‘Glory – that or his skull split for the motherland, or someone else’s crumbles – that is glory.’ (Bagration said), but it’s just hogwash for the rear, and in fact, what have I done? No more than is expected of the Soviet people to defend the Motherland. Today I am willing to go on the attack, even melee, no fear, my own life has grown so hateful, I’m happy to die for the Motherland: how good, to have this opportunity, but I would have to die a nasty death. So many soldiers are killed!”

Two days later, the diary reads, “For three hours now I’ve sat and cried. 12 at night. Who do I need? What good am I? Am I no help? My experience is not wanted. It looks like there are too many support troops, and I will not be called to help. I don’t know, what to do next? Often, I hear dirty talk. For what do I deserve such useless torture? Everyone shouting raunchy, filthy language., nobody to talk to.”

On January 22, Roza and two scouts rushed a German defensive position in an abandoned estate house when the rest of the Soviet infantry were “afraid to go further.” She and the two scouts secured the house from the withdrawing Germans. By this time, Roza had attached herself to another regiment. The divisional commanders cited her actions to shame their men, shouting, “Here is this girl’s example, learn from it.” She was quickly assigned to the divisional scouts.

The diary’s account of that action is dated January 24, 1945. It is the final entry. Three days later, on January 27, Roza was badly wounded by a German artillery strike. She was reportedly shielding an already wounded artillery officer. She died of her wounds the next day. Roza was buried on the battlefield with full military honors. Her remains were later removed to a cemetery in Znamensk, Kaliningrad Oblast, Russia.

Streets in Archangel, Shangaly, and Stroyevske are named for Roza. The village of Yedma, where she spent her early years, has a museum dedicated to her. The school where she studied from 1931 to 1935 features a commemorative plaque in her honor.

Roza’s Compelling Story

The war correspondent Pyotr Molchanov took possession of Roza’s diary after her death. He published a heavily edited version in 1965 in the journal Yunost. More details were released over the years, and the most complete version available in English is now online at rozasdiary.com, along with many photographs.

Being a military historian specializing in World War II, I’ve been aware of Roza Shanina for some time. The Soviets, out of sheer necessity, employed women in combat roles across the board, as the Russian Army had done in the First World War. Many of those women were snipers, with Lyudmila Pavlichenko, “Lady Death,” being the most celebrated.

But I’ve always found Roza’s story to be far more compelling, no doubt because of the look her diary provides us into her innermost thoughts. Most of what we know about Pavlichenko was carefully curated by the Soviet government.

Roza’s complex personality is fascinating. That this 20-year-old woman, who loved children and literature, was clearly a steely-eyed warrior seems at least somewhat contradictory. Her diary goes from mooning over handsome soldiers, being continuously disappointed by their seemingly inevitable rude behavior, and engaging in sometimes juvenile complaints about her fellow female soldiers, to a heartfelt yearning for fierce combat.

Perhaps the knowledge that the Nazis had killed three of her brothers drove her. Roza mentions them little, so that’s pure speculation. Her official score of 59 confirmed kills, with no doubt many more unconfirmed, speaks to her ability and dedication. But she seems to have had an inkling about her fate, despite her battlefield success. She wrote to her mother in January, asking that her younger sister, Julia, be properly educated. Roza herself had taught Julia to read.

As always with someone whose life is intimately recorded, Roza’s death seems a tragedy, as it surely was. But it was a tragedy among millions of other tragedies. Depending on the source, Adolf Hitler’s attempted war of extermination killed 24 to 40 million people in the Soviet Union. Most of them were civilians. In Roza’s case, the war clearly damaged the psyche of, and ultimately killed, an intelligent, talented, and promising young woman.

It seems that Roza knew this too. Perhaps the most tragic words she ever wrote were on the back of an undated photo of her with an unnamed Soviet captain: “War has stolen all the precious time from me.”